SALEM, Ore. — Every two years, Oregon's state economists make a bet on how much taxpayer revenue will come in over the biennium. If they come up short, taxpayers get money back on their returns via the uniquely Oregonian "kicker" rebate.

But after several multi-billion-dollar kickers in a row, economists are going back to the drawing board when it comes to making that bet.

To get out ahead of it: No, the kicker isn't going away — not entirely, anyway. It's been suggested many a time that those billions could go toward improving the services Oregon provides, but it's historically been a third rail of state politics. Most lawmakers are afraid to touch it, so a repeal of the law hasn't been a real possibility.

But it's clear that Oregon's economists have been agonizing over the reasons why their educated guesses keep coming in short by billions of dollars, and they're trying to remedy it.

READ MORE: How does Oregon's 'kicker' tax rebate work?

There are three possible outcomes when state economists make their forecast for the biennium. If the guess comes in close to the mark, there is no kicker but the state will have all the money it needs to fill out its budget. That's really what the economists are trying to achieve.

If they guess more than the amount of revenue that actually comes in, that's a recipe for budget shortfalls — there's no kicker, and lawmakers will need to make cuts in order to meet Oregon's obligations. It's not a good outcome for anyone.

But if the tax revenue that comes in is 2% or more above what economists predict, all of that funding gets sent back to taxpayers as a kicker. And the last couple of kickers have been whoppers: the one Oregonians got back during tax season earlier this year was $5.61 billion.

Breakthroughs in forecasting

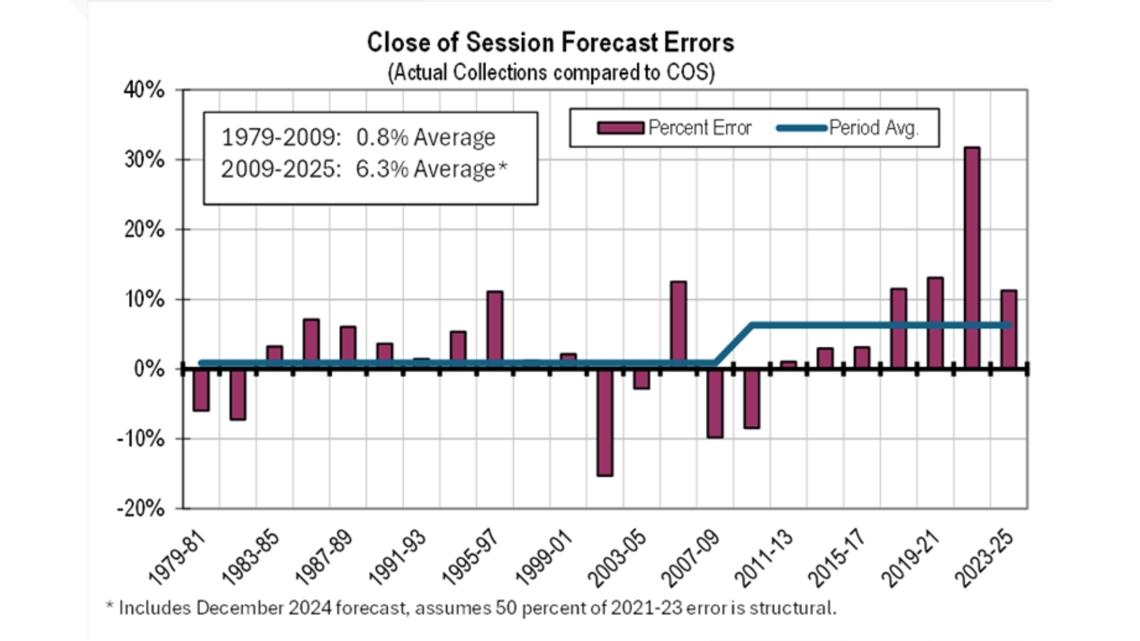

In delivering their latest forecast to lawmakers on Wednesday, the state's Office of Economic Analysis took a "modified analytical approach," they said in a statement. They'd gone back through the past few years and looked for reasons why their forecasts have come in so low compared to the reality — something that's been an issue, to varying degrees, for over a decade.

"The reason for these methodology changes is because the historic forecast errors have increased in magnitude and shown a persistent bias since 2009," the office said in a statement. "OEA’s adjustments are expected to address these issues."

According to the office, they reconstructed Oregon's personal income tax model to reflect "true liability and collections," taking the kicker into account and eliminating "a false signal of weakness" in tax collections this year.

OEA also more tightly aligned the state's revenue forecast and national economic trends, they said.

What does that mean? Well, the state economists are going to adopt a more realistic (or maybe optimistic) outlook on tax revenues, trying to close the distance between those past predictions and real revenues which kept triggering the kicker. It means the kicker could be smaller and less likely to trigger, and they potentially run a larger risk of creating shortfalls. At the same time, the legislature could have more funding for the budget.

Perhaps it's unsurprising, then, that they're predicting that revenues will continue to go up. The 2023-25 General Fund balance is now expected to be $2.79 billion, with revenues increasing by $945 million since the last forecast in September. And for the 2025-27 biennium, General Fund resources are expected to increase by $2.27 billion, gaining revenues of $1.3 billion since the September forecast.

READ MORE: Oregonians likely to get another kicker as state revenues exceed economists' expectations

Most lawmakers reacted to the new forecast with similar statements of cautious optimism, acknowledging Oregon's strong economy while warning of the potential for downturn in the near future.

But Senate Republicans did take precise aim at the changes to OEA's forecasting criteria, and specifically because it could impact the likelihood and size of future kickers. The one gathering steam right now, which taxpayers won't receive until 2026, will not be impacted — that bet's already been made. But it could change the one that would go out in 2028.

“This forecast raises important questions about the accuracy of these projections and their potential impact on taxpayers,” said Senate Republican Leader Daniel Bonham (R-The Dalles). “Oregonians deserve transparency to ensure the system works for them, not just for government budgets.”

Senate Republicans highlighted that Oregonians have received over $11 billion from the kicker in the past decade — money that taxpayers paid in and later received back. But it's also money that the state could conceivably be using to fund things like transportation and schools, were the OEA to get better at making bets.

“The kicker is the people’s money, and it should remain so,” said Senator Lynn Findley (R-Vale), a member of the Senate Finance and Revenue Committee. “While this biennium’s kicker appears secure, changes to the revenue model could lead to smaller refunds in the future, and we need to ensure taxpayers are treated fairly.”

As of this most recent forecast, Oregon taxpayers are expected to get $1.79 billion back from the kicker in 2026, as a return on their 2025 taxes. If past years are any example, that's likely to go up between now and next June.

A new sheriff in town

Within the last year, Oregon's longtime state economist left the job, as did his deputy. The new state economist, Carl Riccadonna, was a Wall Street analyst who has taken it upon himself to get the forecast more in line with reality.

"My mandate joining (the Department of Administrative Services) back in September was to really get to the bottom of what's happening here," he said. "And so, you know, what my team has done is kind of deconstruct and reconstruct a lot of the forecast models to figure out what was happening."

One factor, Riccadonna said, is that the economic forecast was simply too pessimistic. The second is that the kicker itself impacts state revenue forecasts, making a kicker more likely over time because economists weren't properly dealing with how it lands on tax returns.

Michael Kennedy, a senior economist who works with the forecast, explained at length that there were basic assumptions made over a decade ago that introduced this issue.

"We model personal income taxes fundamentally on tax liability — what you'd see on your tax return in terms of tax due," Kennedy said. "In 2011, the legislature passed a law that said instead of getting checks in the mail like you got prior, it became a credit on your tax return. The office had to make a choice whether to make the liability in the model post-kicker, like the real liability, or to model that impact outside the model. And the reason why we chose to make it outside the model was because the kicker is very distortionary. The model would want to, if you had a $5.6 billion reduction in liability, the model would want to reduce withholding — you'd want to reduce estimated payments and want to reduce all those different types of collection across the board, unless you used a lot of elbow grease outside the model. You could just say ... 'People are going to pay less payments at tax time and they're going to get a lot bigger refunds,' and you can make those adjustments very easily. And that was really the decision that was made.

"What you end up with over time though, when you get large kickers, is you've got a model that's basically a world where the kicker doesn't exist and you've got collections that are a lot lower, and you just have the potential there where you're vacillating back and forth — you can easily start to make errors in terms of what you're estimating the real liability to be, and that's what we've seen is if you look back as the kicker gets bigger and that difference gets bigger, the errors get bigger, and you can see you can get this recursive effect where the errors are just going to get bigger and bigger as the kicker gets bigger unless you go back to a world where liability in the model is really the real liability and you don't have this difference."

Riccadonna went to great lengths to express that he's not blaming the former architects of Oregon's revenue forecast. And when asked where his mandate came from — who gave him the mission of correcting the forecast — he said it was just good practice.

During a press conference Wednesday morning, Gov. Tina Kotek briefly addressed the forecasting change.

"I haven't seen this morning's presentation, but I'm aware," she said. "I think that the truing up of the calculation under the new chief economist is really going to be helpful to provide stability when we are trying to do budgeting every two years. And I think his assumptions around the recalculations made a lot of sense to me ... and that's what I have to say at the moment, but we can follow up a little more on that later if you'd like."