SALEM, Ore. — Tax time in Oregon always contains a bit more anticipation than it might in other states, a touch of game show flair, in large part due to the idiosyncratic "kicker" rebate — a subject that surfaces about every two years, coinciding with the state's biennial budget.

But not everyone knows what the kicker is — or why it is — and it's a topic worthy of explanation.

The Oregon Legislature passed the "2 percent kicker" law back in 1979. Here's how it works: Well before the state's 2-year budget gets passed, state economists do their best to make an educated guess on how much tax revenue will come into Oregon's coffers for those next two years.

It's not precisely a crapshoot, but it might as well be. If the actual amount of tax revenue Oregon brings in is less than predicted, everyone loses — lawmakers have to cut budgets and Oregonians are stuck with an ordinary old tax return.

If the economists' guess hits pretty close to the mark, then lawmakers can breathe a sigh of relief on the budget, but Oregonians still get the same old return.

But, if the actual amount of tax revenue is more than predicted — by 2% or above — then taxpayers have hit the jackpot. Everyone gets some of the money they paid in state taxes back, receiving a share of the total surplus revenue.

For example, let's say the state thought it would bring in $100 in tax revenue, but actually got $105. That would mean revenues are 5% more than initially thought, triggering the kicker. Everybody would get a piece of that 5%, or $5, off the top.

How much each taxpayer receives is based on income level, and a lot of people take issue with that part of the law. People with higher incomes get more back, while lower-income people get less, because the kicker is based on the amount of taxes each person paid.

The kicker doesn't show up as a check in the mail every two years, it's given back to taxpayers as a credit on their next tax return. While there's a bill in the legislature this session to make the kicker into a separate check, it's been languishing in a Senate committee since late February and appears dead in the water.

As a result of all this, the latest kicker will likely show up on Oregonians' tax returns next year, with one potential caveat that we'll explore later.

Kickin' it through the years

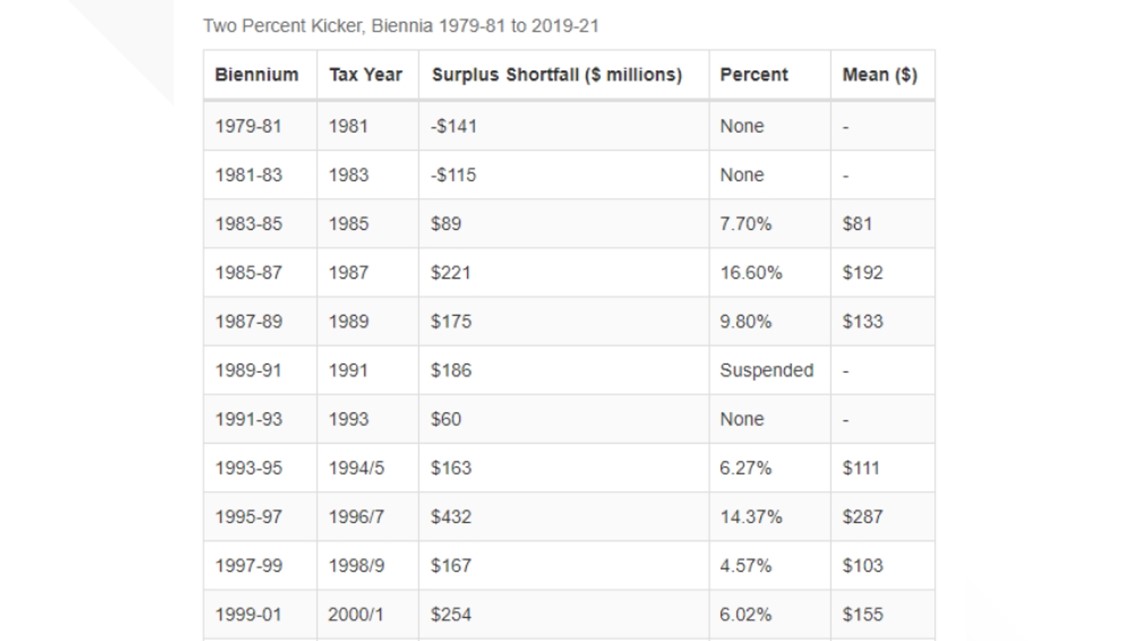

First, it's worth looking at how the size of kickers have changed over time. After the kicker was adopted in 1979, the first few years didn't trigger one — there was a budget shortfall instead of a surplus. But tax revenue started pouring in during the mid-to-late '80s, and the kicker began to kick.

By the late 1980s and again in the mid-to-late '90s, the average amount that Oregonians received back from the kicker ranged between $100 and $300 per person.

Then, for most of the 2000s, the state found itself underperforming — the latter half probably due in large part to the Great Recession after the housing bubble burst. But ever since 2013, things have again been considerably better than economists expected.

The latest number available, from the 2017-19 biennium, had Oregonians receiving over $900 back on average.

For this coming kicker, the kicker surplus is expected to be nearly $4 billion — meaning the kicker that Oregonians receive could be the largest ever by far, perhaps several thousand dollars back for the average taxpayer.

Raiding the kicker

Now to the caveat. Oregon lawmakers could choose to "raid" the kicker surplus in order to fund other priorities instead of sending the money back to taxpayers. Even if the kicker rebate is enshrined in state law, all it takes to grab from the pot is for supermajorities in the state Senate and House to pass a bill that the governor then signs.

Raids and attempted raids on the kicker have happened before, and in recent memory. Within the past few decades, often Democrats are the ones proposing to take from the kicker in order to patch holes in the budget, doing it over the protestations of Republicans.

Among the public, raiding the kicker can be a controversial issue. Who doesn't want to get money back from a state with high income taxes? But some suggest that it could go a long way toward addressing some of the state's most pressing needs in a significant way — funding the Interstate Bridge replacement and other infrastructure needs, or putting serious weight behind efforts to address homelessness, affordable housing, mental health and addiction.

But Senator Elizabeth Steiner, co-chair of the legislature's Ways and Means committee and a Democrat, called raiding the kicker a "third rail" — essentially the political kiss of death — even if she's not a fan of the kicker as a concept.

"There are other places we could find a billion dollars. But if you think tolling is a third rail, talk about the kicker," she told The Story's Pat Dooris. "Because there's $3.7 billion sitting in that kicker and people are talking about whether that should be going back out. Especially since it's pretty regressive and rich people get a lot of it and poor people don't get much at all."

"It's the third rail in Oregon," Steiner continued. "And frankly I'm a little baffled as to why really wealthy people should be getting back a lot of money instead of the state having to pay debt service on that many bonds."

Everyone is going to benefit from a new Interstate Bridge, Steiner reasoned, even wealthy Oregonians who don't cross it often themselves. That's because the bridge is essential to commerce of all kinds.

"If we don't have that bridge, our agricultural producers in eastern Oregon, our grass-seeded farmers down the Valley, our wineries, all those people, our chip manufacturers — they all need that bridge. They all need it," Steiner said. "And if we don't build that bridge and it goes down, not only can we not get across the Columbia, we can't navigate the Columbia because it blocks the entire channel."