SALEM, Ore. — Some aspects of state government are vitally important, but extraordinarily dense — even boring. Nonetheless, it's necessary for the public to have a decent understanding of them. And nothing fits that description better than the state's biennial budget.

Oregon's budget is so big that it's easy to get confused about how the money comes in and goes out. That said, it's fundamentally no different than the average family budget: there's income and expenditures.

But unlike the federal government, the state budget must balance perfectly every two years. It can end with money left over, but the state cannot spend money it does not have — with the narrow exception of bonds.

For help running through Oregon's budget, The Story turned to state Senator Elizabeth Steiner, co-chair of the legislature's Ways and Means committee.

"Big job — being co-chair is a big job," Sen. Steiner acknowledged. "We run a $32 billion general and lottery fund budget for the biennium, and my partner Representative Sanchez and I are primarily responsible for allocating all that."

Breaking down the budget

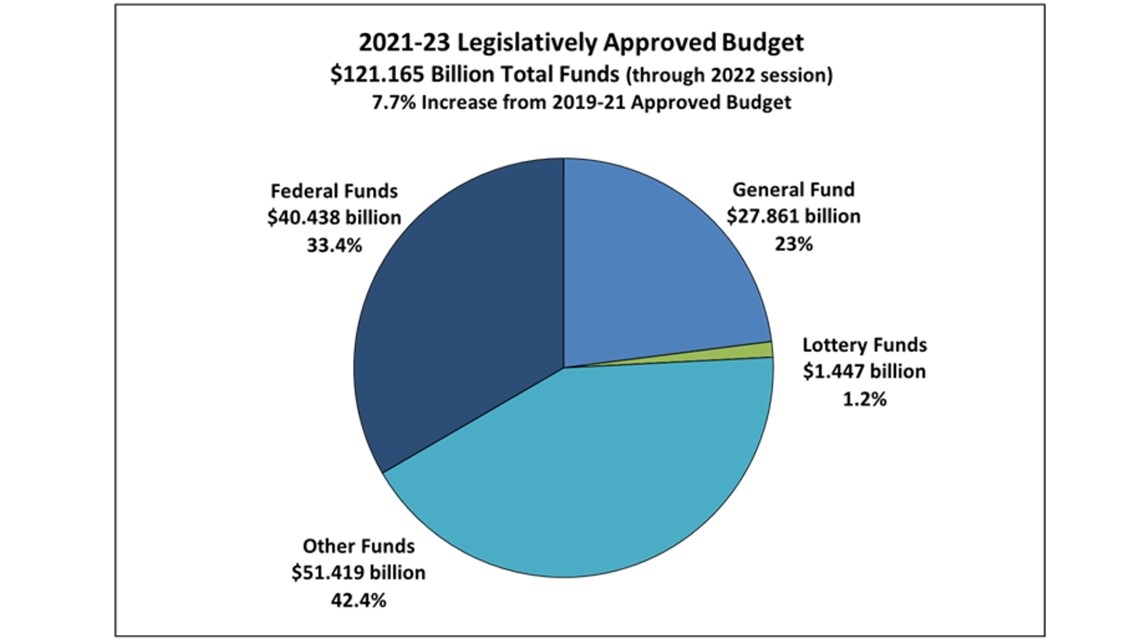

First, let's take a look at where the money comes into the state. In all, state revenue for the 2021-23 budget year was $121.165 billion — which sounds like a mind-boggling amount of money. But most of it is off-limits for Oregon lawmakers.

That funding comes from several areas: the $27.86 billion General Fund, which includes all the taxes individuals and companies pay the state each year; lottery funds to the tune of almost $1.5 billion from state-sanctioned gambling; and almost $40.44 billion from federal funding, which includes money sent to Oregon for programs like Medicaid, education, housing and other programs.

The biggest chunk of the 2021-23 budget was actually $51.4 billion in "other funds," which includes money that state agencies gather by charging for services or licensing — for example, the fee that doctors pay to maintain a medical license, or the fee that many people pay to get a driver's license.

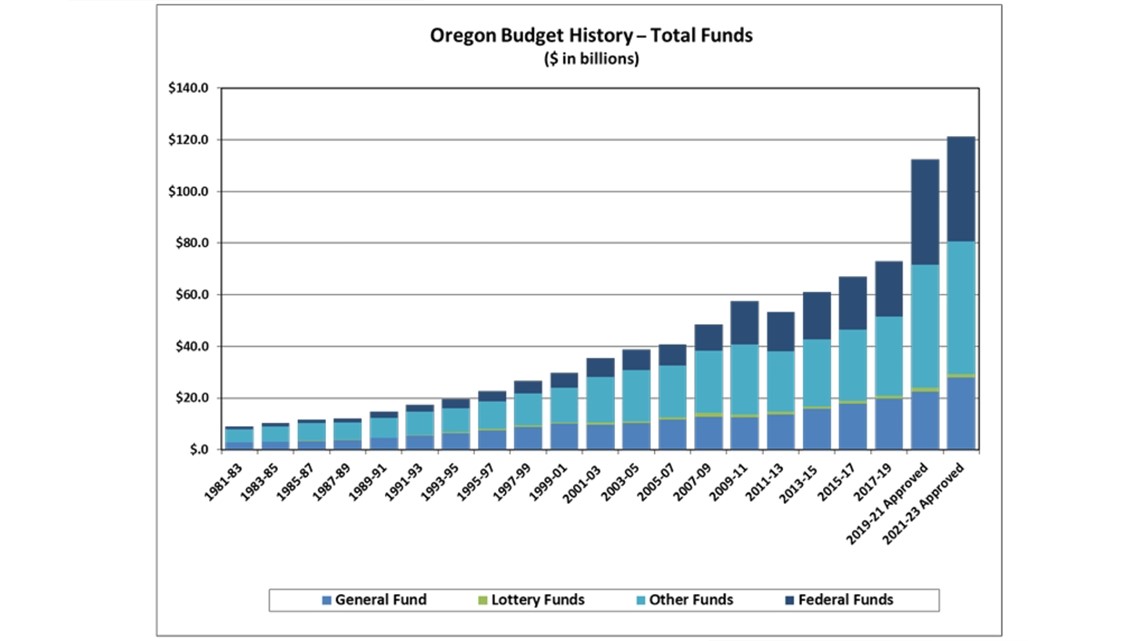

As you might expect, the entire budget has grown considerably within the past several decades. But a lot of that comes from the federal and "other" funds.

Taking a closer look at those sources, the "other funds" are primarily earmarked for things like human services, the state Employment Department and the Public Employee Retirement System, PERS. The federal funding primarily goes toward agencies like the Oregon Health Authority and the Department of Human Services.

But for the purposes of talking about what the Oregon Legislature can spend over the next two years, it's best to ignore everything aside from the General Fund and lottery money. That's the $32 billion that Steiner mentioned up top.

"The $32 billion is what my colleagues and the legislature and I have control over in terms of how we allocate it," she said. "All the rest of it is dedicated and we don't have a lot of control."

Budget cycles happen every two years, biennially, so the next budget will be for 2023-25. And just to further confuse matters, a budget year begins July 1. That means that last year, agencies were figuring out how much money they'd need to keep doing the things they're doing now. They also toss in a few things that they'd like to do if the funding is available.

But, Steiner said, this doesn't mean that everything funded in a budget must keep receiving funds even if they aren't working as intended — state agencies and lawmakers can and do revisit budgets and make savings where possible.

"There are programs that were included for a certain period of time, but they weren't included, for example, in the continuing service level or CSL that we talked about, because we weren't sure if they were going to work or not," she explained. "And we want to see the data — and then if we don't see data that they're working, then we don't fund them again."

Down to brass tacks

For the current budget, which will be done at the end of June, the funding that Steiner and her colleagues had to play with was roughly $29 billion. They'll have $32 billion for the next two years. But even with that big pot of cash, much of it is already spent — on education, for example — and lawmakers can't really touch it.

"What continuing level is for K-12 education is a matter of some debate. But currently the legislature and the chief financial officer says its $9.5 billion for the 23-25 biennium," Steiner said. "The governor put $9.9 billion for her budget, the advocates want another number all together. But at the very least we have to put $9.5 billion, and that's all General Fund, basically. There is some corporate tax ... (but otherwise) it's coming out of that $32 billion."

And then there's the Oregon Department of Corrections, which is another big obligation for the state.

"Department of Corrections is mandatory also, right?" Steiner said. "We have to pay for the cost of every person in custody at the state level ... And that includes all their medical care, food, clothing, paying the corrections officers all that stuff. It's very expensive. Its about $45,000 per year ... per person."

And those big expenses aren't the only state obligations. So taking all of them into account, here's broadly how the budget shakes out for Oregon:

Income:

- $32 billion from the General Fund and lottery funds

Expenditures:

- $9.9 billion, K-12 education

- $3.9 billion, other school-related costs

- $10.7 billion, human services (includes the Oregon State Hospital, behavioral health and raises for home health care workers)

- $3 billion, public safety (includes corrections, state police, district attorney's offices, child support, the Oregon Military Department, and more)

- $1.1 billion, Oregon Judicial Department (includes all state courts and public defenders)

- $785.6 million, natural resources

- $512 million, economic development

- $372 million, administrative services

- $191.5 million, legislative branch

- $155.5 million, transportation

With all of those subtracted, the budget has been whittled down to about $1 billion — and that's where bills passed by the Oregon Legislature take their cut. There's the $200 million that Gov. Tina Kotek requested for homelessness and affordable housing, and $325 million for other expected expenses: additional funding to keep people on Medicaid if federal funds dry up, more money to pay public defenders, money for an emergency fund, raises and bonuses for some state employees. The rest is earmarked for Oregon's rainy day fund.

Conspicuously absent is the $1 billion that Oregon is expected to contribute toward the Interstate Bridge replacement program.

If you can't buy, borrow

Here's where something called bonding comes in. It's an opportunity for the state to borrow money from anyone willing to invest in its General Obligation bonds. Investors give the state money up front, then the state pays them back later with interest.

"GO bonds, general obligation bonds, we can use to build stuff that the state has part ownership of," Steiner explained. "So every two years, something called the the State Debt Policy Advisory Commission ... issues a report that says, 'Here's what we think the bonding capacity of the state is for this upcoming biennium.'"

The commission, Steiner said, determines how much money the state can promise in bonds. That amount isn't infinite — Oregon tries to keep the amount it has to pay down each biennium below 5% of the General Fund.

For the 2023-25 budget, the state can sell $1.9 billion in General Obligation bonds. On top of that, Oregon can sell another $500 million backed by lottery funds.

Steiner and her legislative colleagues are still figuring out what those bonds will be used for, but there isn't enough money for everything on the wish list. On top of the $1 billion expected by the I-5 bridge replacement team, Gov. Kotek has requested over a billion dollars for housing initiatives and more for other programs.

Right now, Steiner isn't making any promises on the bridge.

"That's the number that we have to, that we've been told we have to put up," she said. "It's still under consideration ... I don't want you quoting me saying that I've made any promises, but we have to put up a billion dollars. So there's a billion dollars from Washington, a billion dollars from Oregon, probably close to a billion dollars from the feds and the rest is from tolling."

Right now, it's still accurate that the team working on the new Interstate Bridge proposal expects Oregon and Washington to kick in $1 billion each, but the overall price tag is now up to $6 billion. They're hoping for $3 billion from the feds, with tolling expected to make up the difference.

Unlike a lot of people, Steiner said she doesn't have an aversion to the word "tolling." She grew up on the East Coast, where tolls are more common, and she thinks that user fees are a sensible way for people to pay for what they use.

"Getting back to why it's most likely that the bridge money would come out of bonds ... it's because that is a better place for the money to come out of than cash," Steiner continued. "I can't find a billion dollars. We can't find a billion dollars in the General Fund to pay for that."

The kicker

The 2023-25 budget is still being shaped by Steiner and her colleagues, and then it will need to be passed by both legislative chambers and signed by Gov. Kotek. As a result, some of the numbers listed above could change.

There's even a chance that that the Oregon Legislature will try to pay for the Interstate Bridge replacement in part by using bonds against the Oregon Department of Transportation's State Highway Fund, collected through fuel and vehicle taxes and fees, instead of primarily borrowing against the General Fund. But the remainder would still come from General Fund bonds.

Finally, there's the kicker. That's Oregon's idiosyncratic tax rebate, which goes out to taxpayers if the total amount of taxes collected is at least 2% higher than estimated at the beginning of the biennium.

This year, the kicker could be considerably higher than that — with the estimated amount returned to taxpayers totaling nearly $4 billion. Lawmakers may, as they have before, be tempted to raid the kicker fund. If otherwise left alone, Oregon taxpayers will see a credit on their tax return next year.