PORTLAND, Ore. —

Jason Kesling doesn’t live far from the Telephone Fire in Harney County.

“We're affected by smoke every morning pretty heavily,” he said. “There's a lot of evacuations and stuff going on, a lot of smoke, a lot of concern about what's going on.”

Kesling is also the manager of the Harney County Soil and Water Conservation District, and while his property has remained untouched by the fire, the same can’t be said for many of his neighbors.

Many have lost cattle, access to grazing land and had fences and other infrastructure damaged.

And the Telephone Fire is one of the smaller blazes in that part of the state. The Falls Fire, also in Harney County, had burned more than 143,000 acres as of Thursday morning — one of nearly half a dozen megafires burning in Oregon.

As of Aug. 1, more than 1.3 million acres have gone up in smoke, easily surpassing the devastating 2020 wildfire season. So what has made the start to this fire season so severe, particularly compared to 2023, which was relatively mild?

There are several factors at play — climate change, a history of aggressive suppression, and forest management — and each are related to the other.

For this year, though, the trajectory of the fire season started earlier this year.

“This year, we kind of had the combination of a cooler, wetter spring that leads to a lot of the fine surface fuel build up,” said John Bailey, a professor of silviculture and fire management at Oregon State University. “And of course it dries out, and then you get the ignitions and fires going all over the place.”

Those ignitions are happening in forests that look different than they’ve looked historically, though.

For thousands of years before colonial settlement, Native tribes in Oregon and across the West frequently used fire to clear brush and undergrowth from the landscape. Those practices essentially stopped when Indigenous people were forced off much of their land.

“We definitely have a history where we had a lot of frequent, low-intensity surface fire underneath the trees,” Bailey said. “It was a mistake to completely interrupt that.”

In the early 1900s, the U.S. Forest Service was founded primarily to fight fires. They worked under what was called the “10 a.m. rule,” which mandated that any new fires be extinguished by 10 a.m. the following day.

But that aggressive suppression left forests teeming with fuel — and without the fires the trees had adapted to, Bailey said.

“Fire was part of what created and maintained the Douglas fir forest,” he said. “Attempting to do full suppression all the time, everywhere just leaves all the fuel on the landscape ... and if we don't substitute for the removal of that fuel it's going to burn sooner or later.”

Bailey said that depending on what analysis you look at, Oregon is only using prescribed fire to remove those built-up fuels on a quarter to a tenth of the land needed to successfully manage fuels.

All of that is happening against the backdrop of climate change, which has warmed the climate and caused more intense wildfires and longer fire seasons.

“The slow track of climate change sets the stage for longer and more severe fire seasons each year,” Bailey said.

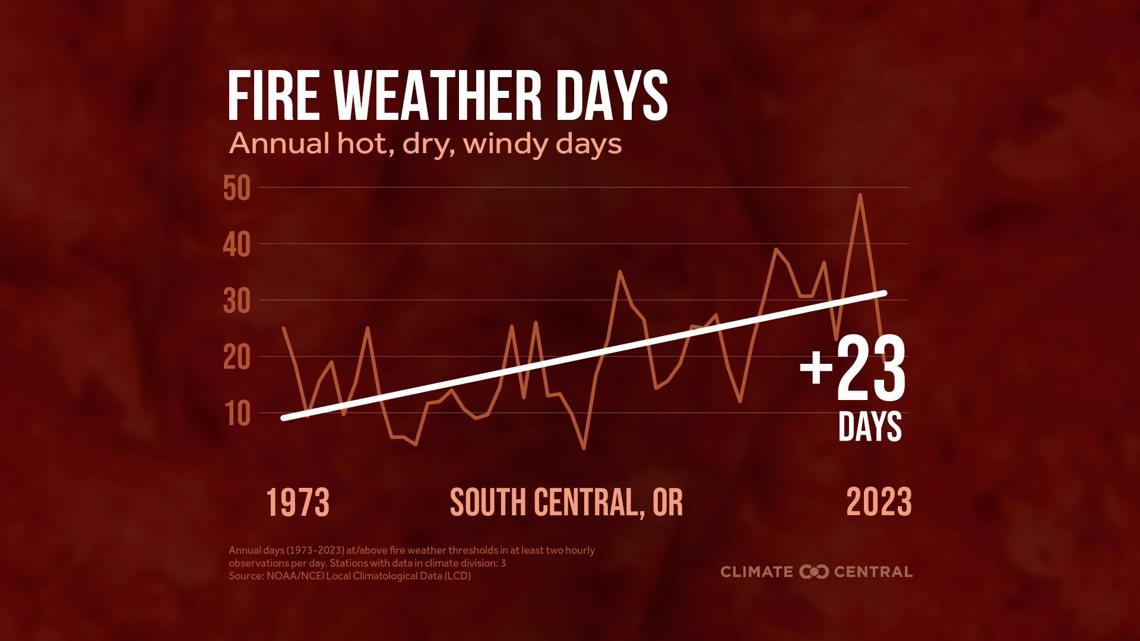

In southern and central Oregon, fire weather days — hot and dry days with strong winds — have increased over the last 50 years, with 23 additional days that fit those criteria per year, according to nonprofit climate analysis group Climate Central.

Of course, none of those factors actually cause fires. Fires are caused naturally by things like lightning strikes — or, more frequently, by humans. Of the more than 1,200 fires that have burned in Oregon this year, more than 70% were human caused.

For Jason Kesling, he’s spending most of his time these days working to find resources for those who have suffered losses in Harney County and helping folks plan for how to rebuild in the aftermath once the fires are out.

But he would also like to see a different approach to the problem from those in power.

“The way we manage our forest is allowing these conditions to fester and become these catastrophic fires,” he said. “I think we should talk to our legislators about these megafires and what's causing them to look for different solutions.”

Bailey concedes that the problems are multi-faceted, but that just means the solutions will need to be, too.

“We're all in this together,” he said. “It's going to take all of us working on these complex problems. It's going to require complex solutions.”