PORTLAND, Oregon —

As Oregon attempts to wean itself off fossil fuels, the state is looking anywhere it can for renewable energy sources.

Even out in the ocean.

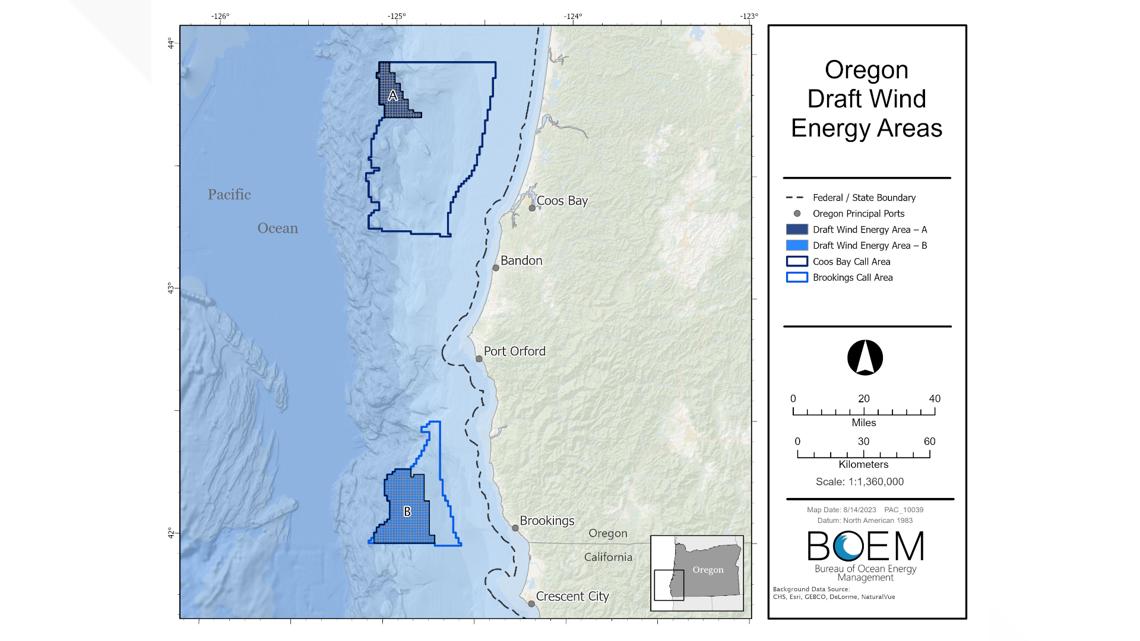

Last week, the Federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) announced two draft Wind Energy Areas off the southern Oregon coast. One of them is offshore of Brookings, near the California border, the other off the coast of Coos Bay.

The areas represent a prime spot for development, with strong, consistent winds that could produce up to 2.6 gigawatts of power when fully operational.

The areas also represent prime fishing grounds and important cultural areas to local Indigenous tribes. Heather Mann, executive director of the Newport-based Midwater Trawlers Cooperative, said it feels like a lot of stakeholders’ concerns are being left unheard.

“They're not listening to coastal communities. They're not listening to the fishing industry. They're not listening to congressional representatives,” said Mann, whose organization represents 32 vessels that fish in the area. “Fishermen are not just concerned about being displaced from fishing grounds, though that is a critical piece. We're also really concerned about any unintended environmental impacts that could come.”

In announcing the two draft wind areas, BOEM Director Elizabeth Klein said they would be taking local concerns into account.

“As BOEM works to identify potential areas for offshore wind development, we continue to prioritize a robust and transparent process, including ongoing engagement with Tribal governments, agency partners, the fishing community, and other ocean users,” she said in a statement. “We look forward to working with the state to help us finalize offshore areas that have strong resource potential and the fewest environmental and user conflicts.”

Looming environmental goals

Last year, the Biden administration set lofty goals for offshore wind energy in the U.S., calling for 30 gigawatts of production by 2030. In 2021, Oregon passed its own ambitious clean energy goals, mandating 100% clean energy by 2040.

And those goals are approaching as demand for energy increases. Many households are adopting electric appliances and home heating systems as more and more people opt for electric vehicles to stem the effects of climate change, which is caused by burning fossil fuels.

Diane Brandt, Oregon state director for Renewable Northwest — a nonprofit that advocates for transitioning away from fossil fuels — said the electric utilities in the region are all forecasting increased demand well into the future.

“The demand just keeps going up, even in last six month, we've seen considerable increases in the utility projections of their demand forecast,” she said.

Brandt said the state has a good idea of how it will meet its early targets, but many questions remain in the long term.

“I think we have a good idea of how to get to 2030, but beyond 2030 — there are a lot of questions about the new resources that can come online because we're going to have less and less gas on the system at that point,” she said. “And so how are we replacing it?”

Much of that energy will come from existing resources like land-based wind, solar and hydroelectric power, but each of those alone aren’t consistent enough to meet the demand that is forecast. Brandt said the wind off Oregon’s coast can help fill in some of those gaps.

“It is blowing at times opposite or complementary to onshore wind,” she said. “It just is another resource to give us a variety of attributes and resources on our grid to make sure that we're getting the electricity when we need it and where we need it.”

Still, offshore wind energy comes has its own unique set of drawbacks that must be addressed, Brandt said.

“There are a lot of concerns and questions like, ‘are our voices being heard?” Brandt said. “Especially from the coastal communities. The fisheries have concerns. The tribes have concerns.”

Gov. Tina Kotek asks for a pause

For Mann, it feels like the federal government is more concerned with meeting the Biden administration’s energy goals than listening to the concerns of the people who will be most impacted.

“At the end of the day, what BOEM is interested in is leasing the land, getting that auction going, so that they can check a box for the administration's goals,” she said.

Some of her concerns are shared by local tribes as well.

The Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Suislaw Indians released a statement earlier this week raising their own concerns about the process.

“The Tribe supports any green economic development project that follows the law and does not harm local fishing jobs, our environment, or Tribal cultural resources,” Tribal Council Chair Brad Kneaper said in a statement. “We cannot support offshore wind development until we are provided assurance that it will do good and not harm the Tribe, its members, and the greater community.”

Noting those concerns, Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek wrote to Klein in June asking the agency to pause the development process so that the state could work with the agency to “provide a deeper appreciation of community interests, to engage in meaningful Tribal consultation, and to develop opportunities to avoid and mitigate potential conflicts.”

“Many valid questions and concerns remain about floating offshore wind,” Kotek wrote. “These must be addressed transparently before we can support proceeding further towards any substantial development decisions on the Oregon coast.”

The agency didn’t exactly pause, but a 30-day comment period on the new draft wind areas was extended to 60 days and BOEM said it would be putting on several meetings, both in-person in coastal communities and online, to hear local concerns.

Mann has her doubts about the meetings, though.

“BOEM will hold as many meetings as you want,” she said, noting that holding a meeting and actually listening to the fishing community were two different things. “It's a one-way relationship. It's not authentic engagement.”

For anyone interested in making comments on the draft areas, online comments can be submitted here.

‘We don’t want to be collateral damage’

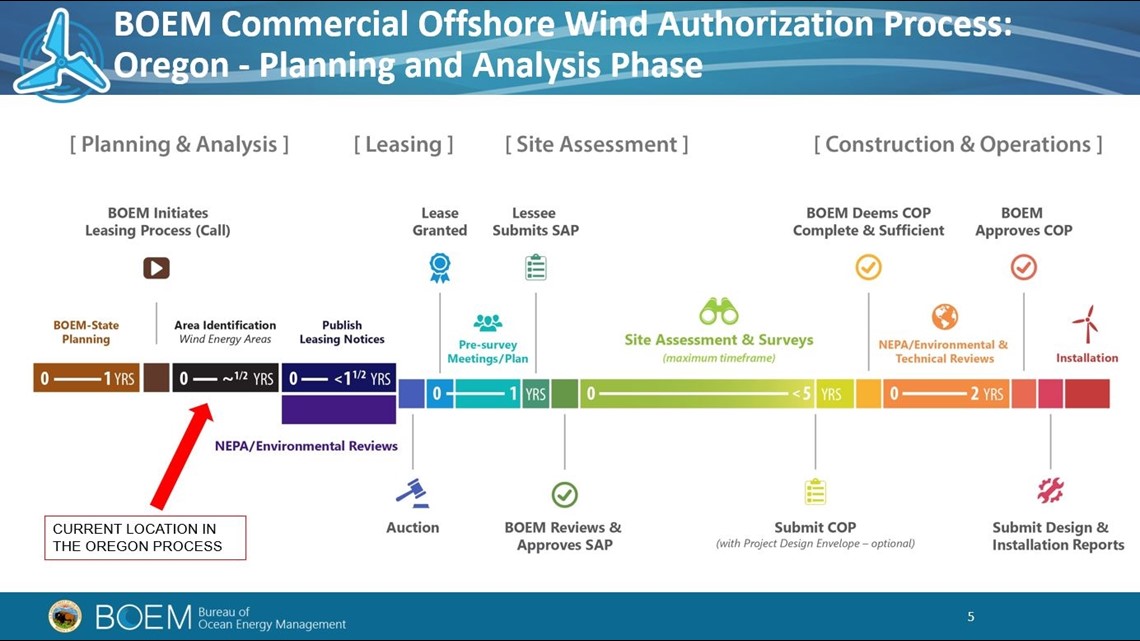

The approval process for offshore wind development is a long one, which has already been ongoing for several years.

If and when the draft wind areas are approved, BOEM will publish leasing notices and there will be an auction for developers to bid on leases for the areas. After the leases are granted, there can be up to a full year of pre-survey meetings and planning sessions.

After that, site assessments and surveys will be conducted, which can take up to five more years, after which the developer submits a Construction and Operations Plan (COP). After another two years of environmental and technical reviews, assuming the COP is approved, construction can commence.

If everything is approved on BOEM’s timeline, that would mean there wouldn’t be turbines spinning off the coast until 2032 at the earliest.

But Mann said, even with that nearly decade-long timeline, the decisions being made now, at the outset, will have the most long-lasting ramifications.

Because the agency isn’t looking at any other areas of the coast, Mann said she fears that even with an extended comment period, moving forward will put her community in jeopardy.

“My concern now is that with this 60-day comment period for the draft wind energy areas, does that put us on a path that is irreversible?” she said. “We've never said no to offshore wind. We've just said, ‘let's do this the right way, the responsible way.”

Mann has been advocating for a reexamination of the whole of Oregon’s coastal waters to look for sites with less conflict, which could set the timeline for the process back considerably. She also wants BOEM to consider sites that are in waters deeper than 1,300 meters, which would cost more for developers, but would decrease the tension with the fishing community.

“People will say, ‘well, the climate crisis is so horrible, we have to do something. Collateral damage is part of the part of the transition,” Mann said. “I think that that's an irresponsible and lazy answer. I think that we don't have to be collateral damage.”