PORTLAND, Ore. —

Sometime in the not-too-distant future, Oregon's coast could be home to some massive new residents.

Wind turbines, some close to 1,000 feet tall and capable of producing up to three gigawatts of power, are planned for two areas about 12 miles offshore near the California border.

There's a long way to go before the blades start spinning and generating electricity to power Oregon homes, but the decisions being made now will shape what the projects will look like when they are constructed in the years to come.

That wind energy future was the subject of the Northwest Offshore Wind Conference, held over two days this week in downtown Portland, where nearly 300 of the country's top experts in the field came together to take stock of the process.

"You've got national labs, universities, regulators, stakeholders and a fair amount of supply chain folks who are starting to realize there's enormous opportunity here if they position themselves well," said Jason Busch, executive director of the Pacific Ocean Energy Trust, a nonprofit that sponsored the conference.

Long planning process

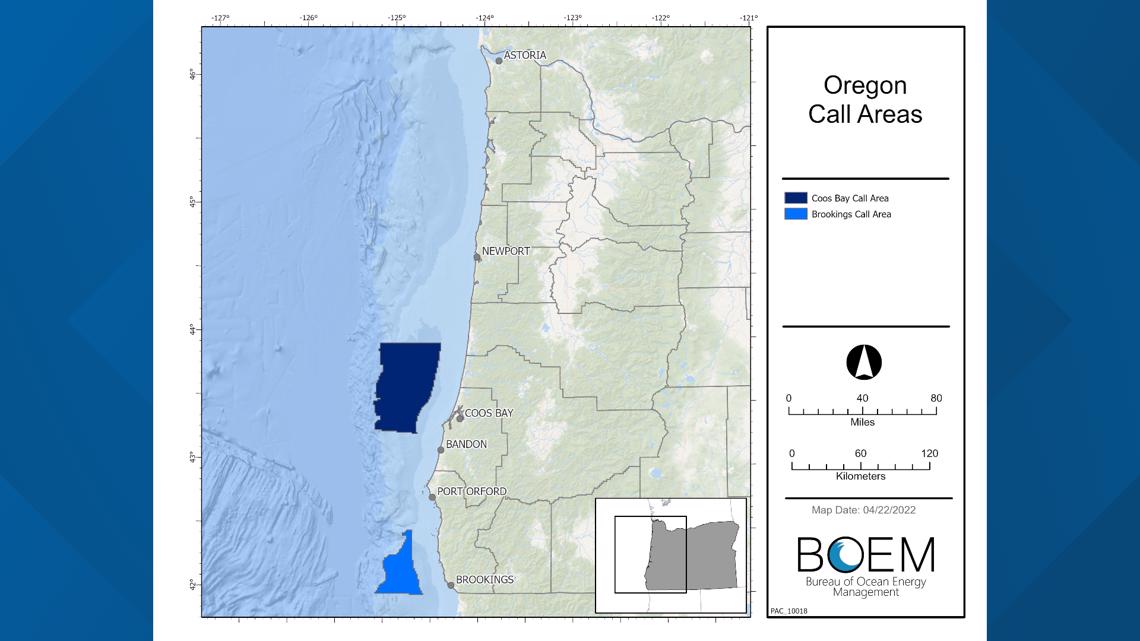

The process of siting, permitting and constructing offshore wind turbines is not a short one. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management began looking at areas off the west coast several years ago and identified two areas in Oregon waters that would be suitable, off the coast of Coos Bay and Brookings.

The coast off of southern Oregon and Northern California is known for having some of the highest potential for wind energy production due to strong, reliable and consistent wind.

Federal regulators have been analyzing the two plots, referred to as "call areas," which encompass more than a million acres, with the intention of identifying the best areas to offer to lease to developers through an auction early in 2024.

One of those developers is Deep Blue Pacific Wind. Peter Cogswell, government affairs director for the company, said it was more than just wind quality that drew him to Oregon.

"What makes Oregon unique is that first you have a world-class resource off the Southern Oregon coast," Cogswell said. "You combine that with Oregon's historic strong support for clean energy policies and decarbonizing our electric supply, and there's a lot to like about offshore wind and how it fits into that environment."

Offshore wind power will also be a necessary addition to the northwest power generation portfolio as Oregon works toward its goal of 100% renewable energy by 2040.

"A lot of people like to think of offshore wind as kind of an either/or while comparing it with land-based renewables, but the reality is, is that we need everything," Cogswell said. "If Oregon is going to achieve its 100% clean energy goals and some of its other decarbonization goals, offshore wind is a critical part of achieving that."

Offshore wind is already in use around the world, including off of the east coast of the U.S. with more than 6,000 turbines providing clean electricity.

Long road ahead

Wind power on the west coast comes with some unique challenges compared to other areas. East coast turbines can be anchored to the ocean floor in the relatively shallow waters off the eastern seaboard, but the continental shelf off the Oregon coast drops off to deeper waters much more quickly, so the turbines will need to be mounted on floating platforms like at some European installations.

That's only one of the challenges facing developers hoping to tap into the power of Oregon wind. Large infrastructure upgrades would be needed at the deep water ports in Coos Bay, and high voltage transmission lines would need to be built to bring all that power onshore.

Wind energy proponents point to all of those challenges as sources for new jobs, but there are other potential hurdles to overcome before offshore wind energy becomes a reality in Oregon.

Fishermen worry that the towers could interfere with their livelihoods. Environmental advocates are concerned that vulnerable marine species could be put further at risk. Tribal groups fear that their cultural resources could be put in jeopardy and that they won't be given the chance to offer any meaningful input on the siting of the turbines.

In an op-ed for the publication CalMatters, Frankie Myers, vice chairman of Yurok Tribe, wrote that Indigenous people have often been ignored when outsiders come to extract resources from their lands.

"Offshore wind presents an opportunity to develop the clean energy America needs," Myers wrote. "But unless offshore wind truly engages with the Native American tribes that suffered the impacts from previous natural resource extraction, it will be as dirty as the rest of them."

And all those potential conflicts are one of the reasons that winning the lease auction is just the beginning of a lengthy process. After that, developers will go through a roughly 7-year period of environmental impact studies, site analysis and surveys of the areas where they plan to build.

That extended period will also provide ample opportunity from all the groups that will potentially be impacted by the development to have input on the process.

Busch said he hopes that the conference in Portland this week will provide a chance to address the concerns of fishermen, environmentalists and tribal members early in the planning process.

"We have something called the Oregon Way, and that means that people have to come to the table and have a dialogue and build trust about how we deal with the controversial or difficult decision making," he said.