PORTLAND, Ore. — When you think of microplastics, you probably think of those tiny bits of broken down material along the beach or out in the ocean like the massive Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

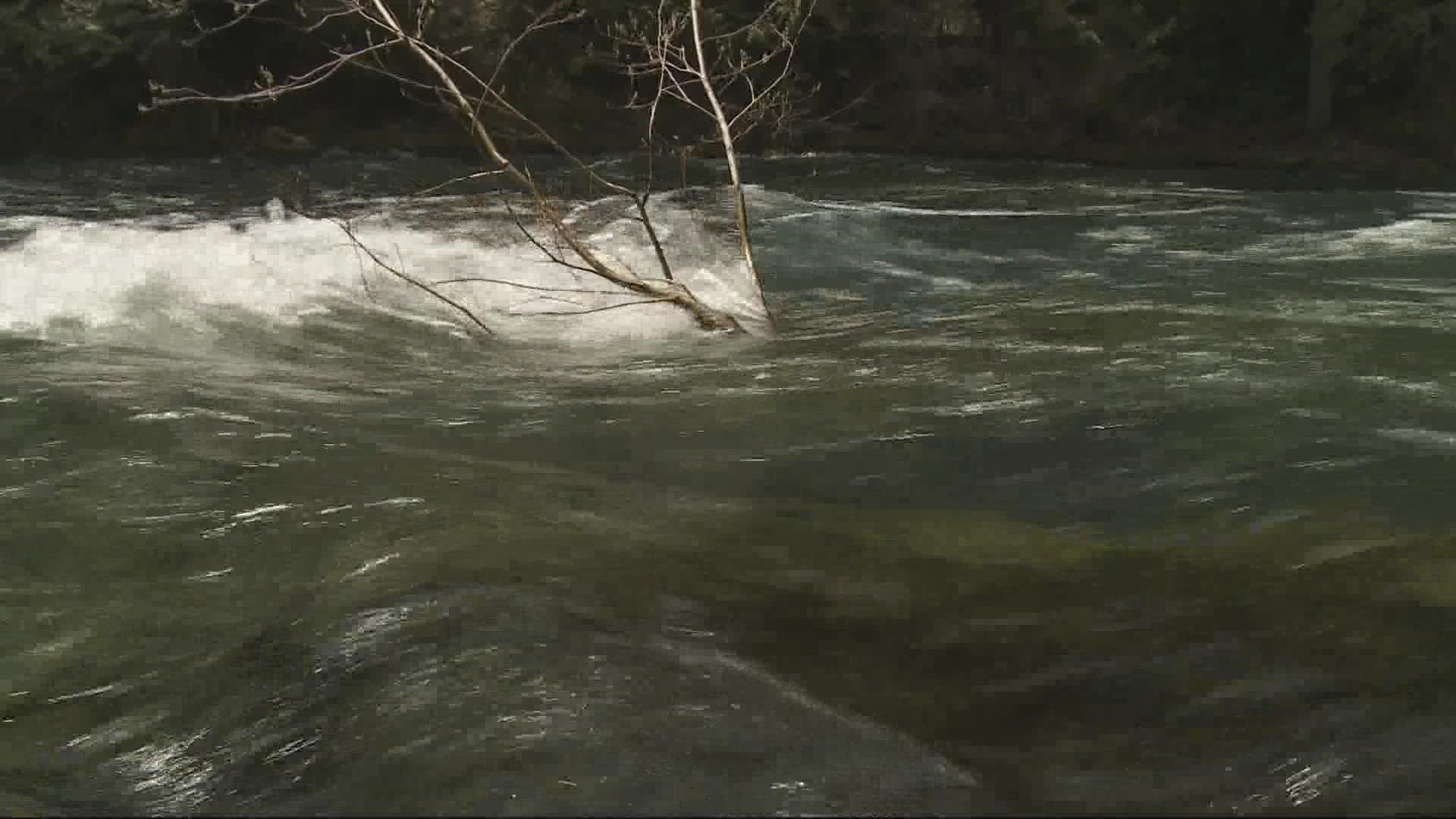

Now, new research from Environment Oregon shows much tinier fibers are winding up in waterways, including some of Oregon's most pristine lakes and rivers.

"What we found was honestly pretty shocking," said Celeste Meiffren-Swango, director of Environment Oregon.

The group recently tested 30 rivers and lakes across Oregon for microplastics.

Microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic smaller than a grain of rice; the most common are microfibers which shed from clothing like fleece. The study found those fibers in each waterway tested.

"From the Willamette River in downtown Portland, and Crater Lake, Wallowa Lake and even some of the most remote places where we were looking," said Meiffren-Swango.

According to Environment Oregon, the impact of these microfibers is still unclear. But research does show the fibers do get consumed.

"Americans consume about a credit card's worth of plastic every single week through exposure to microplastics," said Meiffren-Swango.

In 2019, a study by Portland State University found microfibers in oysters and clams off the Oregon Coast. It found about 11 microplastic pieces per oyster and about nine pieces per clam.

In fact, the study found microplastics in about 99% of the 300 marine animals tested — and nearly all were from clothing fibers.

When we put clothes in the laundry, fibers come off and end up in the wastewater that ultimately goes into waterways.

The PSU study found one load can result in as many as 700,000 micro-filaments going down the drain.

People can keep some of those fibers from getting into the wastewater by using filtering washing bags or buying a special microfiber filter for the washing machine itself.

But the researchers say the most important step is to to limit the plastic produced.

"We need to stop making so much plastic, making so much of our consumer products out of this material that never degrades," said Meiffren-Swango. "We just have to find a better way to live."