PORTLAND, Ore. — You know those fluffy fleeces, yoga pants, and workout clothes so many of us love to wear?

Well Portland State University researchers found out that pieces of those clothes are ending up in the ocean and in our seafood.

Researchers sampled 300 pacific oysters and razor clams up and down the Oregon coast, from spots with lots of water flow and more remote areas, and all but two had microplastics in them. For more reference, that’s about 99% of the clams and oysters sampled.

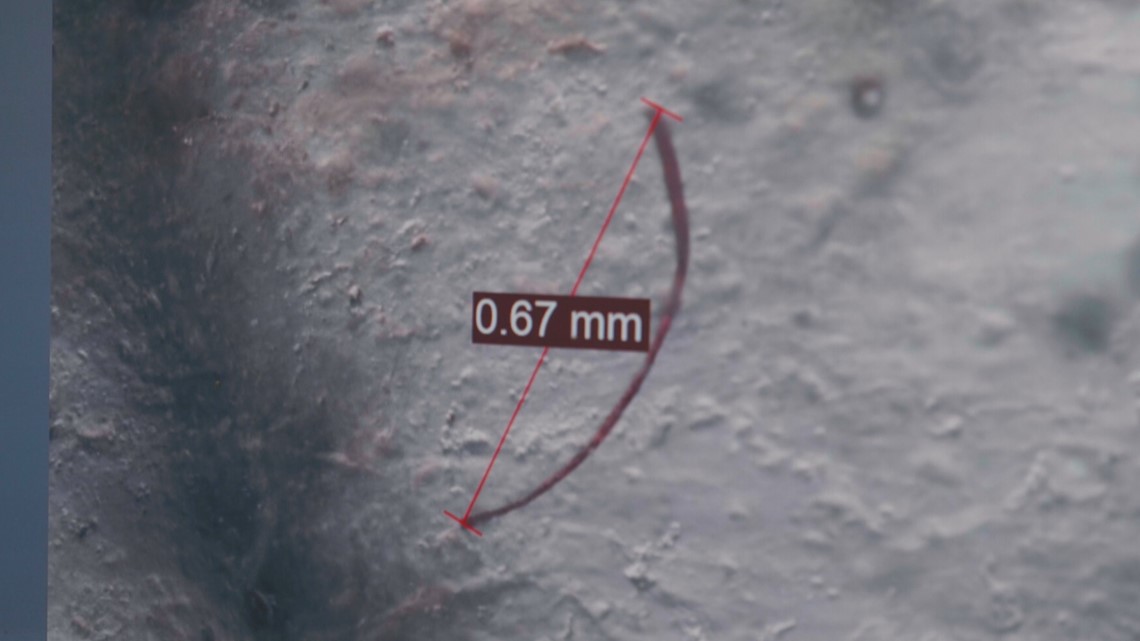

Microplastics are basically tiny threads of plastic that come from the clothing we wear as well as fishing gear.

The study found an average of 11 microplastic pieces per oyster researchers looked at, and nine in each clam.

The overall idea, that the clothing we wear are partly to blame. In fact a load of laundry can result in as many as 700,000 microfilaments getting into our wastewater, then into the ocean and animals.

Professor Elise Granek at Portland State University said researchers expected to see plastics in organisms near big rivers where there's lots of water flow, but there were unexpected findings too.

“What we didn't expect was to see microplastics in the razor clams at all of the sandy beach sites at these open coast sites, some of which are fairly remote,” said Granek over Skype.

She said the study also found a seasonal difference.

“We saw more microplastics in oysters for example in the spring than in the summer,” she said.

Granek said that could be because in the fall, winter, and spring we tend to wear and wash more layers and fleeces.

Studies have shown microplastics affect clams’ and oysters' reproductive systems and growth. So not only can they harm individual animals, but also local populations.

As for what impact microplastics may have on humans if we eat them, Granek said more research needs to be done on that. There's still a lot we don't know, like where in the body the filaments may end up, and how much of it stays or leaves our bodies.

But Granek also said the big takeaway isn’t that we should stop eating seafood, it’s to be more aware of our own contribution to microplastics in our ocean.

Granek said the study shouldn't necessarily deter people from eating seafood, especially because so many people enjoy eating it and it's also a part of the Oregon economy. She said microplastics have been found in drinking water, salt, and beer.

Right now there are efforts to address the problem. Researchers at PSU say engineers are coming up with filters that could attach to washing machines to try and stop microfibers from ending up in the water. But it’s still too early to tell how effective and costly they would be.