HERMISTON, Ore. — As many as 12,000 people in eastern Oregon are in danger of drinking polluted water, drawn up from beneath the Lower Umatilla Basin through private wells. The groundwater used to be safe for humans, but heavy commercial farming and food production have caused nitrates to leach into the aquifer below the basin, building up to dangerous levels over time.

Nitrates in high concentrations may cause miscarriages, thyroid disorders and cancer. They can't be detected by sight or taste in water, and they can't be boiled out. Many residents in northern Morrow and Umatilla Counties have been shocked to learn in recent years that their well water is no longer safe, and some now blame the water for their health problems.

KGW's The Story traveled to eastern Oregon this summer to learn about the problem. It seems like a situation where residents should be able to rely on Oregon's government to protect their water. But for more than 30 years, the state's regulatory agencies have done little more than wring their hands — and the problem has only gotten worse in the meantime.

This is the third of four parts of The Story's investigative series Tainted Waters. Check out the rest here:

'A voluntary approach'

Oregon officials have known for at least 33 years that pollutants have been building up in the aquifer. Back in 1989, the state passed the Oregon Groundwater Quality Protection Act, aimed at preserving and maintaining groundwater resources for future generations. The very next year, samples in northern Morrow and Umatilla counties showed nitrate levels above 10 parts per million, the maximum safe amount set by the EPA.

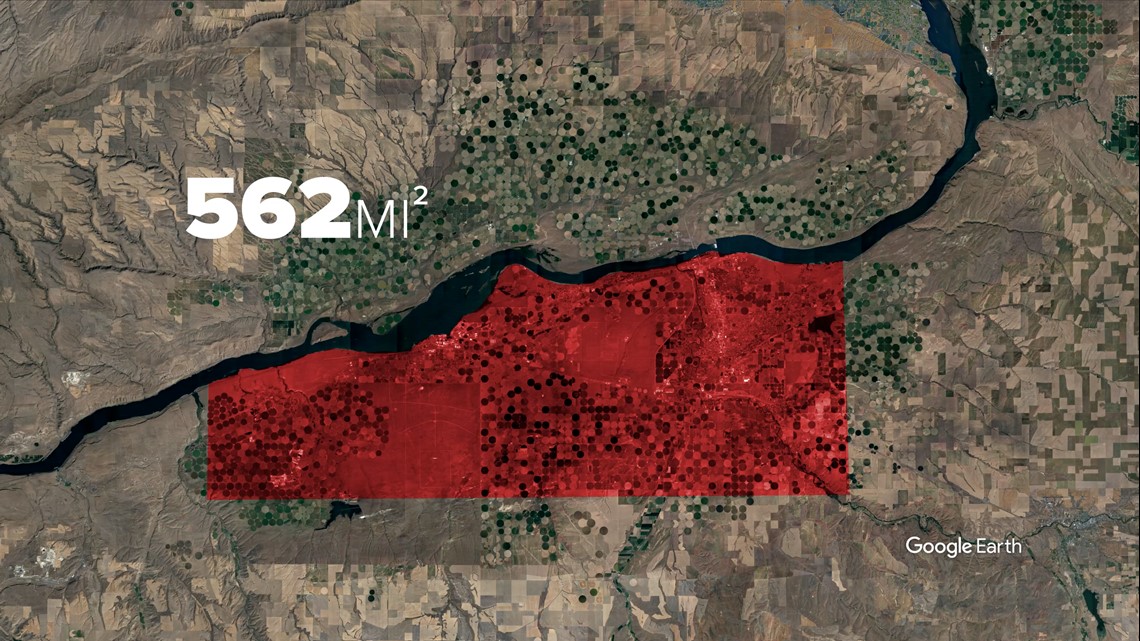

The result triggered the creation of the Lower Umatilla Basin Groundwater Management Area on 562 square miles above the aquifer, and a local committee was set up to "work with and advise state agencies who are required to develop an action plan that will reduce groundwater contamination" in the region.

The committee went through several years of studies and reports, including a study that determined the pollution came mainly from irrigated farming, pastures, confined animal feed lots and commercial food processors. But the committee's membership list — mostly industry and government officials — led to skepticism right from the start.

"It was made up of a hundred percent of folks that were invested in the riches it was bringing, right?" said Jim Doherty, a rancher who recently chaired the Morrow County Commission. "It was the fox guarding the henhouse, if I might."

"It frankly was dominated by food processors and irrigators," added Mitch Wolgamott, a now-retired DEQ official who served on the committee in 2000. "I learned quite early they weren't interested in having a lot of publicity, so people didn't know what was going on... they didn't really have much of an incentive to fix it because nobody was complaining."

In 1997, the committee finally reached a decision to move forward — but without an enforcement mechanism. The committee "agreed to promote a voluntary approach for addressing the groundwater contamination area." There would be no mandatory changes to any practices for any of the major industries that produced nitrate byproducts.

Unsurprisingly, the industry proceeded to keep doing what it had been doing. Outreach programs were created to warn residents with wells, and there were suggestions for industries on best practices — but no one suggested cutting back on nitrate emissions.

DEQ lacks enforcement power

A chronically weak and underfunded DEQ has been able to do little more than watch and make suggestions. Wolgamott said he alerted lawmakers about the problem multiple times over the years and suggested mandatory restrictions might be needed, but nothing was done.

The agency did put out nine annual reports documenting the worsening pollution and outlining public education ideas and industry best practices, but even as that was going on, the Port of Morrow was revealing just how weak the DEQ enforcement mechanisms really were.

The port is bound by wastewater permits designed to protect the aquifer, but DEQ records show the port violated its permits more than 2,000 times from 2007 to 2022 by repeatedly dumping nitrate-contaminated water from food processors in empty fields during the winter. The agency fined the port $129,000 in 2015, but settled most of the other violations.

Finally in October 2023, the DEQ announced the port would pay nearly $2.4 million in fines. But even then, the agency did not require the port to slow or stop its wintertime wastewater discharges until late 2026.

Port leaders declined to talk about their wastewater management practices, but the port is just one of the players in the Umatilla region. DEQ director Richard Whitman discussed the full scope of the region's problem during a May 2022 DEQ commission meeting, and said that DEQ does not have the laws it needs to protect Oregon's groundwater.

"(The port is) by no means the only source of groundwater contamination in that area," he said. "We know that we also have groundwater contamination that's resulted from some of the confined animal feeding operations... we also and perhaps more broadly have issues with regard to fertilizer application by agricultural operators."

Residents left frustrated

Some Umatilla basin residents who spoke to KGW said they were surprised by recent unsafe well tests, but others said they just felt angry and disillusioned about the apparent unwillingness of local officials and inability of state regulators to do anything about it.

"Our county commissioners could stop it, but they don't. They could say no. The port commissioners could say, 'No, let's clean it up.' They don't," said Mike Pearson, who lives in the Umatilla Basin.

"I'm embarrassed for the leaders in our community," added Raymond Akers, who recently switched to bottled water after his well water tested at nearly three times the safe limit for nitrates. "Those who have covered it up and kicked it under the rug for so many years."

While chairing the Morrow County Commission in 2022, Doherty declared a countywide state of emergency after a round of testing found dangerous nitrate levels in water from wells that were previously deemed safe.

"Somebody had to stand up," he said. "You know, I said as a politician, you're always faced with a challenge, right? Is this the hill you're willing to die on? When I looked at this, I said, 'You know, this literally is the hill I'm willing to die on as a politician.'"

The first groundwater committee eventually gave way to a second, which was later shut down, and now, a third committee is studying the problem. In August 2023, that third committee gathered for a work session in Boardman — but the meeting ended up highlighting how little progress has been made so far.

"We have our groundwater database that doesn't talk to DEQ's groundwater database, that doesn't talk to what (the Oregon Health Authority) is doing, or what the counties are doing," summarized one exasperated attendee.

This is part 3 of The Story's reporting. Part 1 aired Monday and focused on the residents impacted by well water contamination. Part 2 aired Tuesday and focused on the sources of the Umatilla aquifer pollution. Part 4 airs Thursday and examines efforts currently underway to solve the nitrate pollution problem.