HERMISTON, Ore. — For decades, thousands of eastern Oregon residents have relied on private wells to supply them with drinking water — but now a crisis is unfolding, with a growing number of homeowners discovering that their well water has begun to carry dangerous levels of nitrates, which may cause miscarriages, birth defects and cancer.

The explanation is straightforward up to a point: the wells all tap into a massive aquifer beneath the Lower Umatilla Basin, a regional hub of commercial farming and food production. Fertilizer and animal waste are big sources of nitrates, which can seep into the groundwater. But tracking the nitrates back to their sources — and stopping them — is more complicated.

KGW's The Story traveled to eastern Oregon this summer to learn more about the problem. The first part of this multi-day story focused on the residents who say their health has been impacted by the increasing contamination. Part two focuses on where the pollution comes from, speaking to the region's farmers and industrial food producers.

This is the second of four parts of The Story's investigative series Tainted Waters. Check out the rest here:

Nitrates leaching into groundwater

In the rolling hills near Echo, about 8 miles southeast of Hermiston, the red onion harvest gets underway in early September. Jake Madison owns a farming operation that spans 10,000 acres, and he explained that the onions go through multiple rounds of testing over the summer.

"So like on these onions, we come out and pull tissue tests," he said. "We pulled like eight to 10 tissue tests during the key periods, from the first of June to the end of July."

The tests are to figure out how much fertilizer the onions need — or how much they don't need. If too much liquid fertilizer is applied, it can easily drain into deeper ground and reach the aquifer.

The surrounding countryside was carved by the great floods during the last ice age that left behind a combination of sand and silt and gravel. It's great soil for growing potatoes and onions, but it's not so good at filtering out nitrates.

"Not any one farm is the problem," said Mitch Wolgamott, a retired Oregon Department of Environmental Quality official who once oversaw the eastern region. "But when you have thousands of acres that are being irrigated fairly heavily and fertilizer put in these really porous sand soils in the area, it's very difficult to keep it from leaching down into the aquifer."

The risk is highest near Boardman, Irrigon and Umatilla due to local soil conditions. It's more moderate at Madison's farm, but he still does extensive testing because he participates in a special program.

"We know every kind of nitrogen that's going on the field. We know where it's going," he said. "We've got soil tests on the front and back end to make sure we can prove we're not leaching it everywhere."

The problem is that Madison's farm is the exception. For most of the 180,000 acres of irrigated farmland above the fragile aquifer, there are no restrictions on how much liquid fertilizer can be put on the land, and no restrictions on when it can be applied.

And without regulation, there's no way to track how much actually gets used.

Who polluted the aquifer?

As Wolgamott mentioned, there's no individual culprit, but the fact remains that groundwater under a large part of the Lower Umatilla Basin is contaminated with nitrates, with some areas containing hazardous levels.

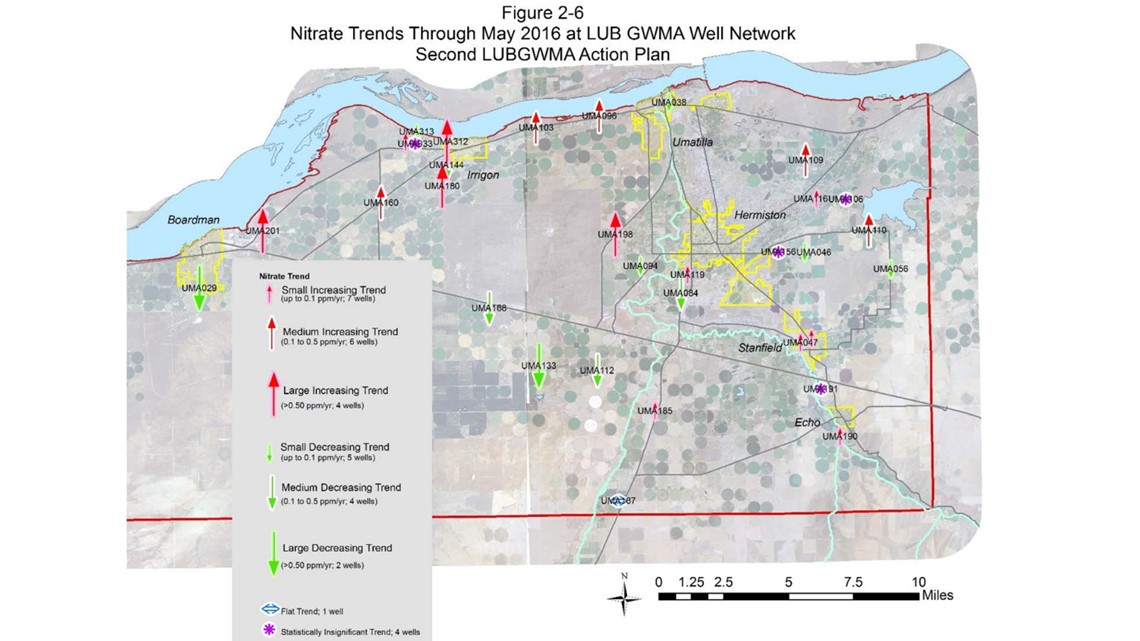

The potential contamination stretches over 562 square miles, putting as many as 12,000 residents in danger. State maps illustrating test well results from 1991 through May 2016 show that 52% of wells in the region had increasing trends of pollution, while 33% had decreasing trends and 12% had no change.

A trio of state agencies studied the issue back in 2011 and found three main contributors: irrigated agriculture, pastures — most likely in the form of animal waste — and food processors where companies wash produce brought in from the field. Irrigated agriculture was the biggest source, accounting for roughly 82% of nitrate contamination. Pastures produced about 8%, and food processors about 4%.

"It started with the advent of large-scale irrigation in this area," Wolgamott said. "With the increase in agriculture, of course you get food processors to deal with the products that are being grown, and that creates wastewater that is also rich in nutrients, so we have both wastewater and fertilizer."

Researchers believe farmers played a big role in the contamination by putting too much liquid fertilizer on the ground in the past, but it's unclear if current farming practice are still making things worse. When scientists look at groundwater samples, there isn't a good way to tell if they're seeing nitrates from days ago or years ago — or where they came from.

Oregon has given lip service to doing something to help, but none of the involved agencies appears to have taken ownership of the overall problem, and the result is that the state has failed to make meaningful change for more than 30 years, and the problem has only gotten worse in the meantime.

The Port of Morrow

The Port of Morrow is another big source of nitrates, and it's easier to track because its water use is regulated. The port is a huge economic engine for Morrow County, with 46 companies located in its industrial parks paying more than $100 million in taxes. In a county with nearly 13,000 people, 6,300 jobs are directly or indirectly connected with the port, so any move to restrict the port's business is fraught with economic and political danger.

The port's largest tenants are food production companies that wash the onions, potatoes and other crops that pour in from local fields. The resulting wastewater contains nitrates, and the port collects and stores millions of gallons in holding ponds, while sending as much as 10 million gallons per day to farmers like Jake Madison.

Since the wastewater is already rich in nitrates, using it for irrigation allows farmers like Madison to cut down on their own fertilizer use — that's the special program mentioned above. Madison is such a valuable outlet that the port built a 16-mile pipeline directly from Boardman to his farm in Echo.

But while the process works for Madison, the port still has more wastewater than it can get rid of — and it's been reprimanded for dumping excess water on empty fields during the winter. In June, the Department of Environmental Quality fined the port more than $2 million for more than 2,000 dumping incidents.

The department recently amended the port's wastewater permit to allow it to keep spreading nitrate water during winter months for the next few years — but starting in November 2026, it has to stop between November and February.

The port refused KGW's request for an interview and tour, but public documents show the port has promised to invest $200 million to help solve the problem. It plans to build a huge storage lagoon and take other steps to strip much of the nitrates out of the water before it gets sent out. But fully solving the problem could be even more expensive.

"First off, to take care of our nitrate issues, regardless of whether others do anything, is going to cost the port upwards of 500 to 600 million bucks, maybe more than that," then-commissioner Marv Padberg said during a candidate forum event in May hosted by the Boardman Chamber of Commerce.

It's unclear where the port will get the money. And Madison noted that stripping nitrates out of the water won't solve the bigger problem, because the whole point of reusing the port's wastewater is to cut down on farming fertilizer.

"I still need nitrogen to grow the crops," he said. "So I'm gonna go buy fertilizer to put on the crops now. So it's like, 'Okay, it didn't really change anything.'"

This is part 2 of The Story's reporting. Part 1 aired Monday and focused on the residents impacted by well water contamination. Part 3 airs Wednesday and delves further into the history of the regulators tasked with protecting the region. Part 4 airs Thursday and examines efforts currently underway to solve the nitrate pollution problem.