SALEM, Ore. — For months, Oregon lawmakers from both parties have been working on ways to tackle the state's drug problems. They rolled out a more complete result of those efforts Monday night in Salem, during the first day of what promises to be a whirlwind 35-day legislative session.

At the center of the drug policy proposal are changes to Measure 110, the landmark voter-approved initiative that decriminalized drugs starting in 2021. While lawmakers' proposals go well beyond what Measure 110 impacted, tweaks to the law make up the core of the bill.

The Joint Committee on Addiction and Community Safety Response met at 5 p.m. to roll out the details of House Bill 4002, which was outlined in a pre-session meeting last month. While the committee itself is bipartisan, HB 4002 is largely the brainchild of Democrats on the committee — Republicans previewed their own more drastic bill weeks ago.

The co-chairs of the committee are both Democrats and former prosecutors. Rep. Jason Kropf hails from Bend, and his career includes work as a public defender in Portland and later as a deputy district attorney in Deschutes County. Sen. Kate Lieber is from the Beaverton area and spent time as a prosecutor in Multnomah County.

Both lawmakers believe that that drug decriminalization under Measure 110 did not work as intended, and certainly not how voters expected.

Under Measure 110, possession of small amounts of drugs became a Class E violation, essentially a $100 ticket that can be waived if the violator contacts a substance use helpline. Quantities vary somewhat by drug, but here are a few examples that qualify for the ticket:

- Less than 40 pills of hydrocodone, methadone or oxycodone

- Less than one gram of heroin

- Less than one gram or five user units of fentanyl (this was added to state law in 2023)

- Less than one gram or less than five pills of MDMA (ecstasy and/or molly)

- Less than two grams of cocaine or methamphetamine

The new proposal, HB 4002, would change all of these violations to a Class C misdemeanor, a crime punishable by a maximum sentence of 30 days in jail; a $1,250 fine; or both. It's the lowest level of misdemeanor, but it does represent a crime instead of a violation.

In short, everything decriminalized under Measure 110 would be re-criminalized, albeit at a low level. Republicans and other Measure 110 critics are arguing that it should be a greater charge: a Class A misdemeanor, which is the highest level of misdemeanor and one step below a felony. These carry a maximum sentence of up to 364 days in jail; a $6,250 fine; or both.

Both sides say that they want to build in ways for drug users to seek treatment instead of receiving a jail sentence. In HB 4002, this is called a "deflection program." It would be coordinated by a local mental health authority, would be free to the person using it, and would need to be available within 30 days of the person being referred there by police.

For those who attend the deflection program — receiving a behavioral health assessment and showing up to a follow-up appointment — the entire Class C misdemeanor would go away, although the mechanism for doing so isn't as simple as just waving a magic wand.

Jessica Minifie is with the Office of the Legislative Counsel, which helps write the actual laws and explains it back to lawmakers. She described in painstaking detail how people who go through the deflection program would then earn an "affirmative defense."

"Basically, there is a defense — an affirmative defense — for this new Class C misdemeanor if the person completed a qualified diversion or deflection program that they were referred to when they were contacted by the police officer concerning the conduct constituting possession," Minifie said, "or if they were never referred to a qualified deflection program when they had that contact with the police.

"That second defense can only be asserted by the defendant if the police officer had probable cause for no other charges at the time. There is a notice requirement for the defense, so the defendant would need to provide notice to the state of the intent to assert the defense at least 21 days before the first trial setting. The notice needs to be accompanied by any document that the defendant intends to rely on in improving the defense; the terms 'completion' and 'qualified deflection program' are defined terms in the bill. ... Completion basically means that you conducted a screening and one additional contact with the deflection program."

The idea behind the change is to get drug users caught in possession to engage more concretely with the Oregon behavioral health system, such as it is, or face some criminal consequences. Right now, law enforcement officials complain that the Class E violations are largely treated as a joke — and all the evidence thus far has shown that practically no one contacts the Measure 110 helpline.

HB 4002 would also set up a task force to study Oregon's mental health system and attempt to build in more accountability. That portion prompted a question from Republican Sen. Fred Girod of Stayton.

"What I would like to see in that bill is something to the effect of the dollar amount we're spending on something versus the efficacy, and that would give you the dollars per success," Girod said. "Because we can throw a lot of money at the wall, and if we're not getting any successes out of it, then it's really money not well-spent. I'm a big opportunity-cost sort of person. We got an Oregon Opportunity Grant we're not funding, and so I want to make sure that if we're gonna spend all this money, then we are actually going to get some success out of that."

That's been a growing concern for many Oregonians, particularly in Multnomah County — not questioning whether the money needs to be spent, necessarily, but whether it's being spent on programs that are making a measurable difference.

Sen. Elizabeth Steiner, a Democrat from the Beaverton area who co-chairs the legislative committee that essentially holds the state's purse strings, said she asked the same question earlier in the day.

"They brought up the very interesting point that it's hard to define success in substance-use disorder treatment," Steiner said. "In part, for example, if you have somebody who was using opioids and is now only using cannabis — is that a success or a failure? Well, we don't really know. And there's not clear standards in the literature ... and how we collect data on some of these programs — for example, community outreach programs where people go out and try to build trust with people living on the street so they can eventually get them into treatment — how do we measure that? ... You know that I am a staunch supporter of evidence-based policy, Sen. Girod, and that's why I was struggling to ask these questions."

Lawmakers covered much more ground during Monday night's hearing, and they'll cover even more during subsequent hearings as the session unfolds. It's likely that aspects of HB 4002 as introduced will be amended before it comes to a vote in either chamber.

Taking the measure of Measure 110

Though Oregon voters overwhelmingly approved Measure 110 back in November 2020, public sentiment has clearly shifted in the intervening years amid rising homelessness, deadly fentanyl overdoses and growing visibility of public drug use. It's considerably less clear, however, that those can be attributed to Measure 110, coinciding as they did with the COVID-19 pandemic and a major sea change in the street drug supply.

In January, a group of researchers gathered in Salem to present some of the studies that have been done on Measure 110 thus far. It was led by an organization called RTI international, a nonprofit research firm often contracted by the federal government.

Researchers wanted to look at whether Measure 110 has moved the needle on things like fatal overdoses, drug treatment and law enforcement response in Oregon.

Since drug decriminalization happened well before funding for treatment got out the door, the research that looked at overdoses and policing over the space of several years are perhaps the most useful for looking at the outcomes of Measure 110.

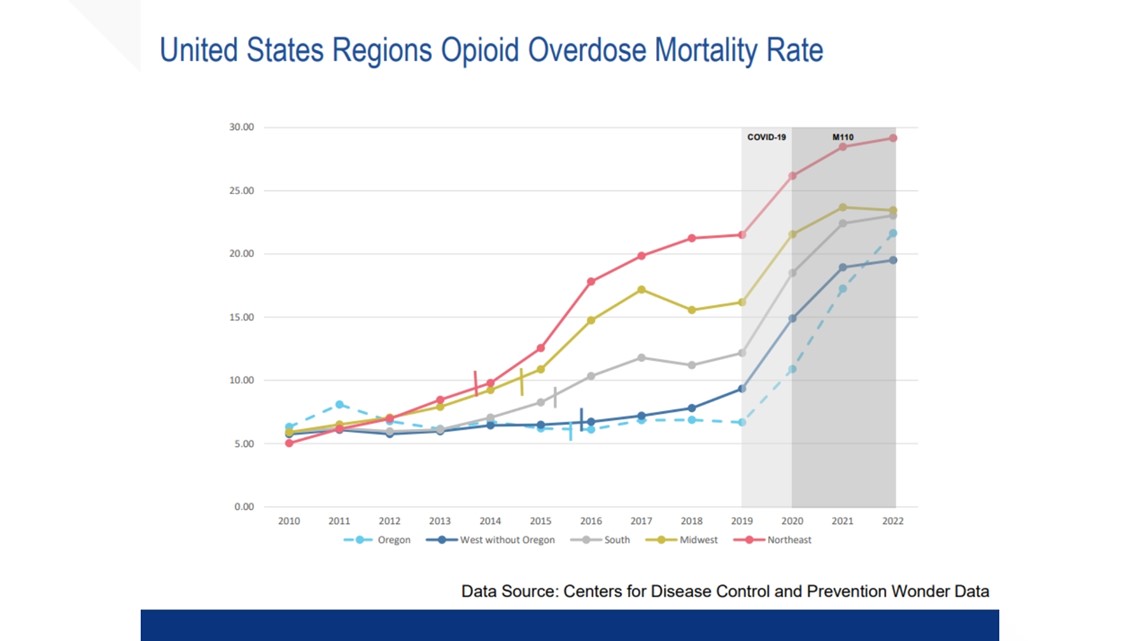

A study conducted by RTI looked at overdose mortality rates throughout the country. Rates began rising sharply in other parts of the country much earlier than in the western U.S. as synthetic opioids like fentanyl first made their appearance — as early as 2014 in some areas.

Deaths from synthetic opioids didn't begin climbing in western states, including Oregon, until around the time COVID-19 hit in 2020.

By then, fentanyl was beginning to take over the drug supply on the West Coast, and mortality rates from synthetic opioids skyrocketed. Drug decriminalization didn't take effect in Oregon until 2021, and overdose were already rising sharply by then.

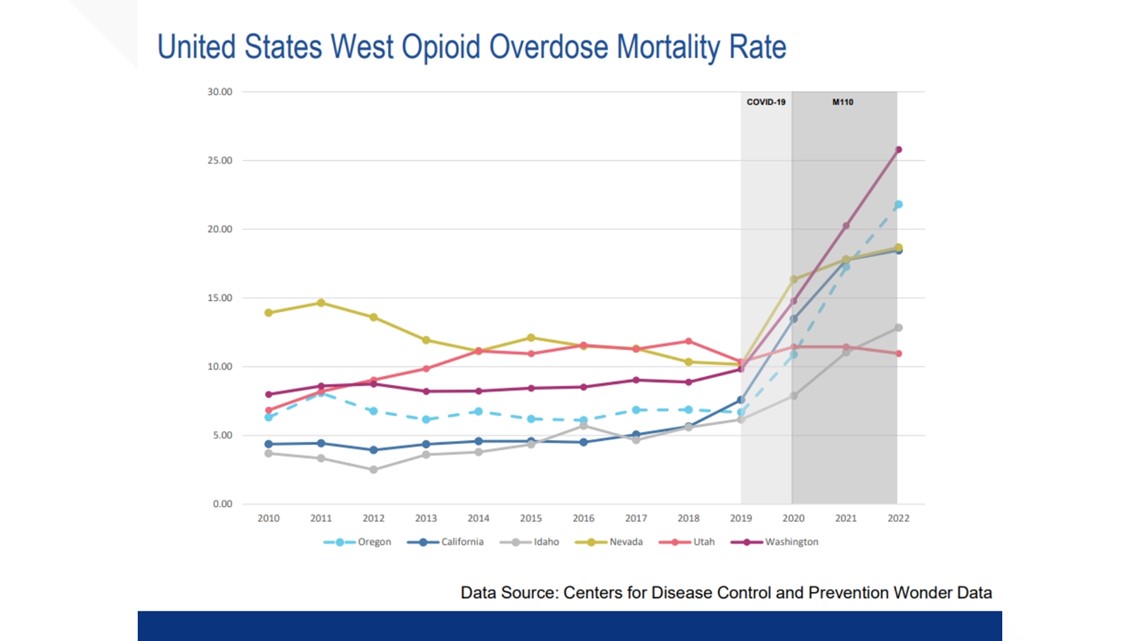

In some western states, opioid overdose deaths did begin to level off over the course of several years. In Oregon, they continued to climb into 2022 — but they were climbing in Washington as well, where the mortality rate has been consistently higher.

Drugs were briefly decriminalized in Washington after a 2021 court decision, but lawmakers quickly passed a temporary law making simple possession a misdemeanor. That law failed to curb the rise in overdoses, according to the RTI study.

Researchers on the RTI study concluded that the reason for the spike was because of the influx of fentanyl, not Measure 110. They suggested that if the western U.S. follows trends in other regions, overdose deaths will begin to level off over the space of several years. Two other studies came to similar conclusions.

Another group of studies tried to determine if Measure 110 was responsible for an uptick in crime. One study conducted at Portland State University looked at arrest data, finding that arrests of all kinds dropped sharply in Oregon during the pandemic. They've since begun to rise again but have yet to reach pre-pandemic levels.

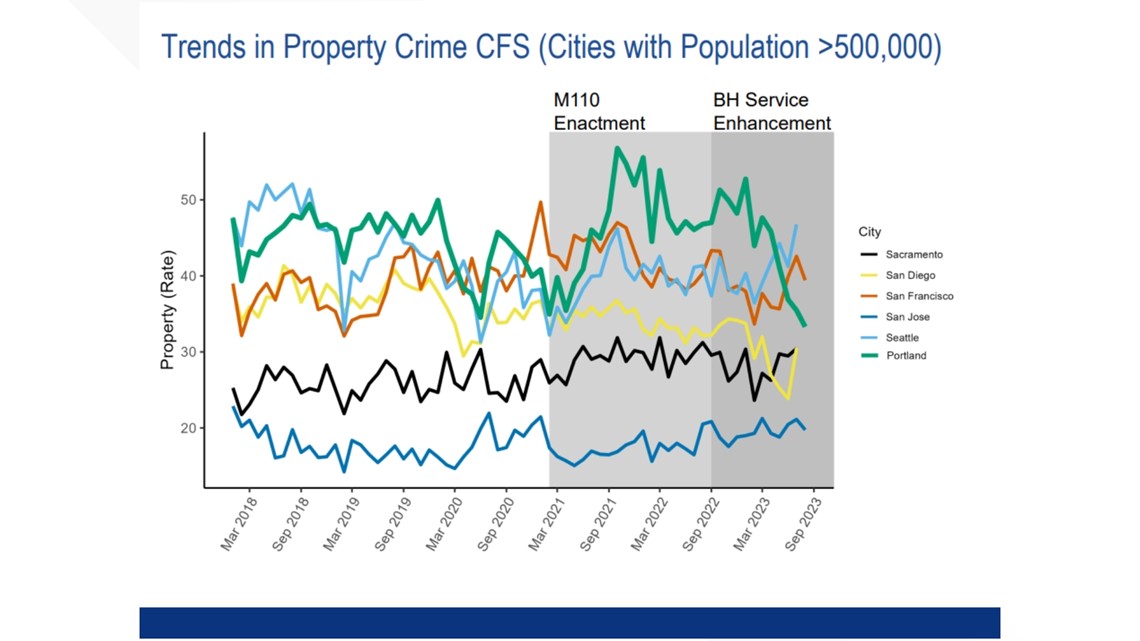

While Portland did see a spike in calls about property crimes — things like vandalism and theft — immediately after the passage of Measure 110, RTI International found, those began to drop again in 2023. None of the research found any association between Measure 110 and violent crime.

DID MEASURE 110 TAKE AWAY 'ROCK BOTTOM'? Oregon cops seem to think so

Researchers also attempted to dig into interactions between drug users and police. A survey of drug users in Oregon found that, in spite of Measure 110, 73% have some recent or ongoing involvement with the legal system — either through police stops, jail time or probation. More than half said that they've been stopped and searched, and nearly half said that police had seized drugs from them.

Many users reported being totally unfamiliar with the Class E citations that Measure 110 allows for, and users tended to report that interactions with police were inconsistent and unpredictable — either they reported being completely ignored by police despite using drugs in public, or they reported being searched and their drugs confiscated.

In one survey, a startling 7% of users reported knowing that Measure 110 had decriminalized fentanyl.

Meanwhile, a study by NYU Langone Health noted that racial disparities in arrests decreased in Oregon after Measure 110 but remain "extremely high." Arrests for drug possession among Black people fell more than their white counterparts — however, Black people were still over two times more likely to be arrested. Native American/Pacific Islanders were arrested at nearly four times the rate of whites.