PORTLAND, Ore. — Within the last 9 years, Oregon has tinkered three times with laws surrounding low-level drug possession, the kind aimed at drug users rather than dealers. Most members of law enforcement will say that the first two did not majorly impact the way they enforce drug crimes. The third was Measure 110, approved by voters in 2020.

For the uninitiated, Measure 110 decriminalized drug possession at user amounts. It also directed a significant amount of Oregon's revenue from cannabis taxes toward an array of drug treatment-related programs.

According to those law enforcement officers, Measure 110 has single-handedly done a number on the justice system in Oregon communities.

Researchers at Portland State University are partway through a 3-year study on Measure 110, and their first report just came out. That's where we're learning more about law enforcement sentiments surrounding the measure.

The results probably won't come as a surprise to anyone, no matter what side of the issue they fall on. Cops in Oregon feel that Measure 110 has been a complete failure. But the PSU researchers are withholding judgment, saying it's too soon to know for sure.

The study

The PSU study is the work of three researchers, bankrolled by the U.S. Department of Justice for this 3-year effort. The first year focused on talking with law enforcement officers from 10 agencies in six different counties, half urban and half rural. Multnomah County is one of them.

The Story's Pat Dooris had a chance to talk with one of the PSU professors, Christopher Campbell. According to Campbell, most officers don't think Measure 110 is working because people with drug problems are not getting help at the necessary rates.

"One of the things we found is that officers are skeptical of how decriminalization can motivate people to voluntarily seek treatment, which is manifested into officers being far less willing to hand out citations," Campbell said. "For instance, one officer we spoke to from an urban sheriff's office suggested that they believe Measure 110 took away the system's ability to recognize their rock bottom, so to speak, and kickstart a new life void of drug use. So this, along with many other reasons, leave officers feeling like giving out citations isn't really worth their time. This issue was really mentioned by about every interview — about 96% of every interview — and it really bears out in the data when we look at arrests and citations."

RELATED: Oregon modeled Measure 110 on Portugal's drug decriminalization. They aren't remotely the same

Researchers came away with five main themes after talking with police. First, officers feel that Measure 110 took away their probable cause to search for crimes related to addiction and drug use, like theft — and because of that they are not stopping as much crime.

Also, the officers said, it's harder to find informants willing to help them take down the big drug dealers and distributors since they've lost leverage with the users. After Measure 110, police say they can't threaten drug users with prosecution if they don't cooperate. Those two issues led to a drop in proactive policing, the officers reported.

Police also feel that Measure 110 is all carrot and no stick. People found using drugs can be cited and encouraged to seek treatment, but they don't face much in the way of punishment for failing to do so. So some officers are hesitant to even issue the citations allowable under Measure 110 — they think it's a waste of time.

RELATED: Portland police increase 'walking patrols' downtown in response to increase in overdoses and crime

The researchers said police are frustrated, feeling that there's no way to stop people from committing drug-related crimes.

"Many officers believe that without that traditional system of carrots — that is, dropping charges so to speak, in a drug court sense — and sticks — that is, the use of jails — then there's no way to stop people from committing crimes related to drug use," Campbell said. "So the concern now is, where do we get that point-of-contact of treatment? Where do we get folks engaged with treatment if not through the criminal justice system, which was drug court typically, or just using the charges to hold over their head?"

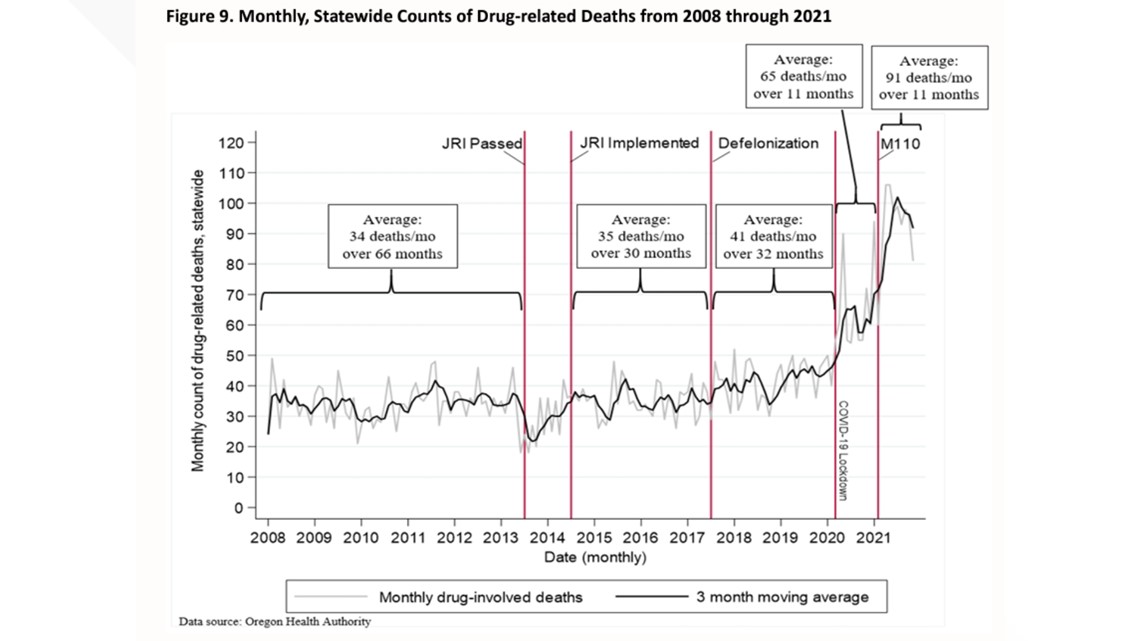

There's also the spike in drug-related deaths in Oregon. The study includes a graph that shows a climbing number of these deaths, beginning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those numbers continued to rise after the passage of Measure 110, though there are signs that the worst may be over. Drug deaths dropped in the latter half of 2021 after rising steadily for a year.

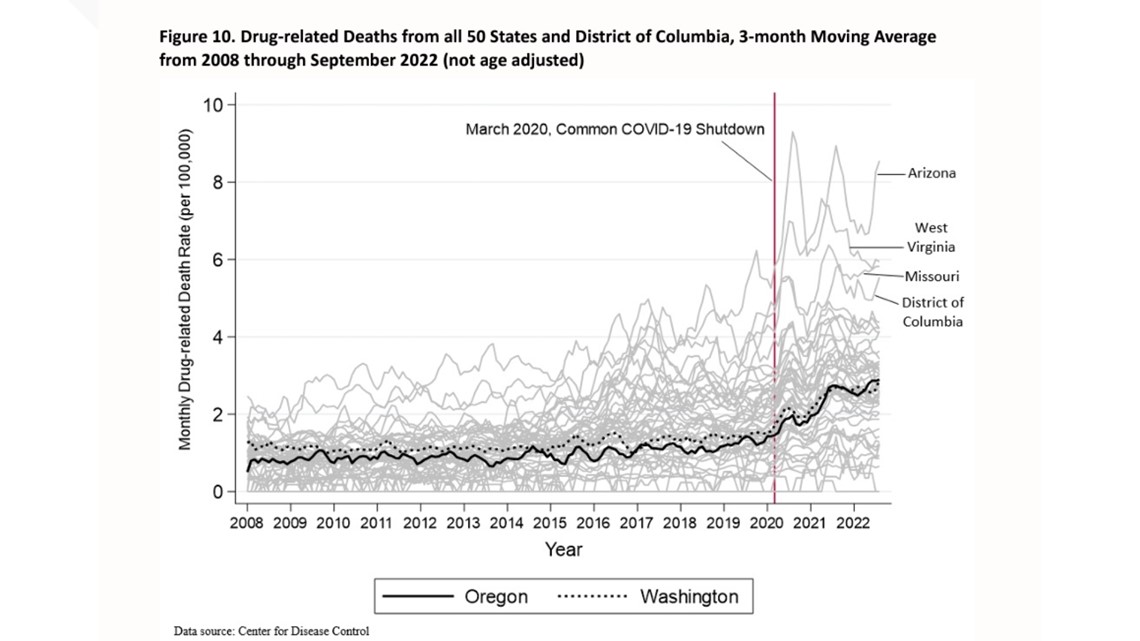

"We wanted to couch the fact that yes — Oregon, first of all, is experiencing a spike in drug-related deaths. And it is very critical and it is very important that we focus on that as a social problem," Campbell said. "However we also have to couch that in the fact that the rest of the nation is also experiencing a very similar rise in drug-related deaths. So it's not just Oregon. And if it's not just Oregon, then it can't just be Measure 110 ... So there's a number of factors that could be going into this. And that's one of the reasons why we say it's too early to say, because we just need a little bit more follow-up time from when Measure 110 occurred and then what happens after that."

Though Oregon is the only state in the country to have embarked on drug decriminalization of this scale, the study looked at data that showed the state broadly mirroring drug death trends in neighboring Washington.

While certainly higher than in previous years, Oregon's drug overdose mortality rate in 2021 was far from the highest in the nation. The worst states for drug overdose deaths that year per capita were West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee and Louisiana. In fact, Oregon and neighboring Washington and California were comparable, and all in the lower half of U.S. states for drug overdose mortality rate.

At the same time, there are signs that Oregon's drug crisis is worsening more quickly than in other states. Also in 2021, overdose deaths in Oregon rose 41%, compared to a nationwide increase of 16%. Those increases are fueled by fentanyl and more powerful forms of methamphetamine.