What you need to know before Jeremy Christian's trial begins

The self-described white nationalist is accused of stabbing three men aboard a MAX train in May 2017, following a hate-filled tirade at two teenage girls.

Nearly three years have passed since a deadly stabbing aboard a MAX light rail train changed Portland forever.

Two people were killed, one was severely injured, and the tragic incident brought increased concern over - and a national spotlight on - hate-filled tension in Oregon, a state with a history of racial division.

Fast-forward to the present - the trial for the man accused in that attack, Jeremy Christian, is set to begin Jan. 28, 2020. Here's what you need to know about the attack, and what has happened since then.

Attack on a train Chapter 1

It was a brisk but clear spring day in late May 2017. Dozens of people boarded a crowded Green Line MAX train in downtown Portland as the commuter line headed east toward Clackamas Town Center.

According to police, after a day of drinking sangria wine, a white man named Jeremy Christian, then 35, started hurling hate speech and “biased language” at two black teenage girls, one of whom is Muslim and was wearing a hijab.

According to witness reports, Christian went on to yell about "decapitating heads." The train operator told passengers on the train several times, “if you don’t knock it off in the first car, I’m calling the cops.”

As the train pulled up to Hollywood Transit Center, passengers, including Micah Fletcher and Taliesin Myrddin Namkai-Meche, urged Christian to stop yelling at the girls.

Witnesses said the two men approached Christian, and according to a psychological evaluation requested by Christian's legal team, an unreleased video of the incident "reflected all three [men] being chest to chest."

According to that same evaluation, Christian then recalled "challenging" Fletcher and Namkai-Meche by asking them repeatedly, "What are you going to do?"

Christian then says he pushed one of the men in the chest and Fletcher told him to get off the MAX, before Fletcher "grabbed him and pushed him down onto a seat multiple times."

That interaction is confirmed through video evidence, according to the evaluation.

Quickly, the situation escalated and documents say within just 11 seconds, Christian took out a knife and stabbed Fletcher, Namkai-Meche and a third passenger, Ricky Best.

Police officers and EMTs quickly arrived at Hollywood Transit Center, finding half a dozen good Samaritans attempting to resuscitate Namkai-Meche and Best.

Namkai-Meche was taken to the hospital, where he later died. Best died at the scene. Fletcher was hospitalized with a large slash across his throat.

Christian ran off the train into a nearby neighborhood and tried to ditch the knife he used in the attack, but he was quickly arrested, according to documents. Inside an officer's car, police say Christian quickly admitted to the stabbings.

The victims Chapter 2

Taliesin Myrddin Namkai-Meche, 23, was a Reed College graduate from Ashland, Oregon.

His mother posted the following message online after the attack: "My dear baby boy passed on yesterday while protecting two young Muslim girls from a racist man on the train in Portland. He was a hero and will remain a hero on the other side of the veil. Shining bright star I love you forever."

Ricky Best, 53, was an Army veteran and a City of Portland employee with the Bureau of Development Services.

Immediately after the attacks, his son said he wanted people to hear a phrase his dad said a lot during his life: “I can’t stand by and do nothing.”

Micah Fletcher, 21, was a Portland State University student at the time of the attacks. He was hospitalized for several days, and released from the hospital.

In an interview with KGW shortly after the attack in 2017, he spoke about how Portland is "supposed to be a city where people can be safe."

Fletcher and Christian actually crossed paths about a month before the attack at a tumultuous protest in Southeast Portland.

The two girls who police say Christian verbally attacked have mostly stayed out of the media spotlight, but have spoken with the online publication LitHub. Both said they received threatening calls and messages immediately following the attack.

"As of now, we’ve been quiet about everything. We haven’t talked about it much, not even with each other. I feel like at some point Walia [Mohamed] and I should talk about it more and go to therapy together," Destinee Mangum said. "Post-traumatic stress disorder is real. I don’t want to wait and be scarred for life. I also don’t want that for Walia. I want us to do it together, not separately. We’ve tried to forget about it. But we can’t forget about it. We’re reminded of it every day."

Christian's outbursts and trouble behind bars Chapter 3

Jeremy Christian was initially charged with two counts of aggravated murder, one count of attempted murder, two counts of second-degree intimidation, one count of being a felon possessing a restricted weapon.

As his court appearances have unfolded over the past couple of years, Christian, who has described himself as a white nationalist, has used them as an opportunity to shout political commentary, and even target one of his alleged victims.

Just days after the stabbing at his first court appearance, Christian yelled "death to the enemies of America" and said, "You call it terrorism, I call it patriotism. You hear me? Die."

Shortly after the attack, a Portland woman named Demetria Hester came forward and said she encountered Christian on the night before the deadly stabbings, also on a MAX train.

She said Christian threw a water bottle at her at the Rose Quarter MAX station, and in turn, she maced him and called 911. Since the attack, she has expressed her disdain at Portland police for not arresting Christian that night.

While Demetria was testifying in court in April 2019, Christian had yet another outburst -- this time targeted at her.

"I'm the victim, you're on video macing me. You're on video macing me, liar. Liar!" Christian yelled before being escorted out.

According to jail misconduct reports obtained by KGW through a public records request, Christian got into trouble just four days after the stabbing, by telling a female inmate he was going to tear the cell door from the hinges and rip her head off. He then threatened a deputy.

“He told me, ‘I slash throats for a living,'” deputy Gretchen Rosa wrote in an incident report.

One day later, Christian was in trouble again for being disruptive and failing to follow orders after refusing to remove a jumpsuit covering his cell window.

Then, on June 1, 2017, Christian was written up for being disrespectful to a deputy after using a racial slur.

“Christian immediately asked if we were going to belly chain him when he came out on a walk, and said, ‘You and that n***** sergeant can go f*** yourselves,'” deputy Ryan Cook wrote in an incident report.

Christian was also involved in two fights behind bars, according to the jail reports.

On April 2, 2018 Christian scuffled with an inmate during a walk inside the jail. The other inmate was taken to the hospital to get stitches for a cut on his nose. Christian was not seriously injured. Christian was ordered on lock down for 35 days as punishment for the fight.

On July 29, 2018 deputies say Christian assaulted another inmate, Aundre Mills, in his cell. Prosecutors later dismissed a misdemeanor assault charge in the case.

A drawn-out process Chapter 4

The pre-trial process for Christian has crawled over the past couple of years, mostly due to hearings and defense motions.

In February 2019, Christian's lawyers announced they would intend to use the "mental disease or defect" defense.

A month later, they argued they wanted to move the trial out of Multnomah County, which was eventually rejected by the judge. In May 2019, the judge announced the trial was being delayed to 2020 to give the defense more time to prepare.

What remained up in the air for several months was the possibility that Christian could be given the death penalty if he was convicted of aggravated murder. Around the same time, Oregon legislators passed Senate Bill 1013, which narrowly defined the circumstances under which someone charged with aggravated murder could get the death penalty:

- Murdering two or more people as an act of organized terrorism

- Intentionally killing a child younger than 14

- Killing another person while in jail for a previous murder

- Killing a police, correctional or probation officer

In October 2019, the judge sided with Christian's lawyers: he was no longer eligible for the death penalty and his charges connected to Best and Namkai-Meche's deaths were changed to first-degree murder. If convicted, the longest sentence he can receive is life in prison.

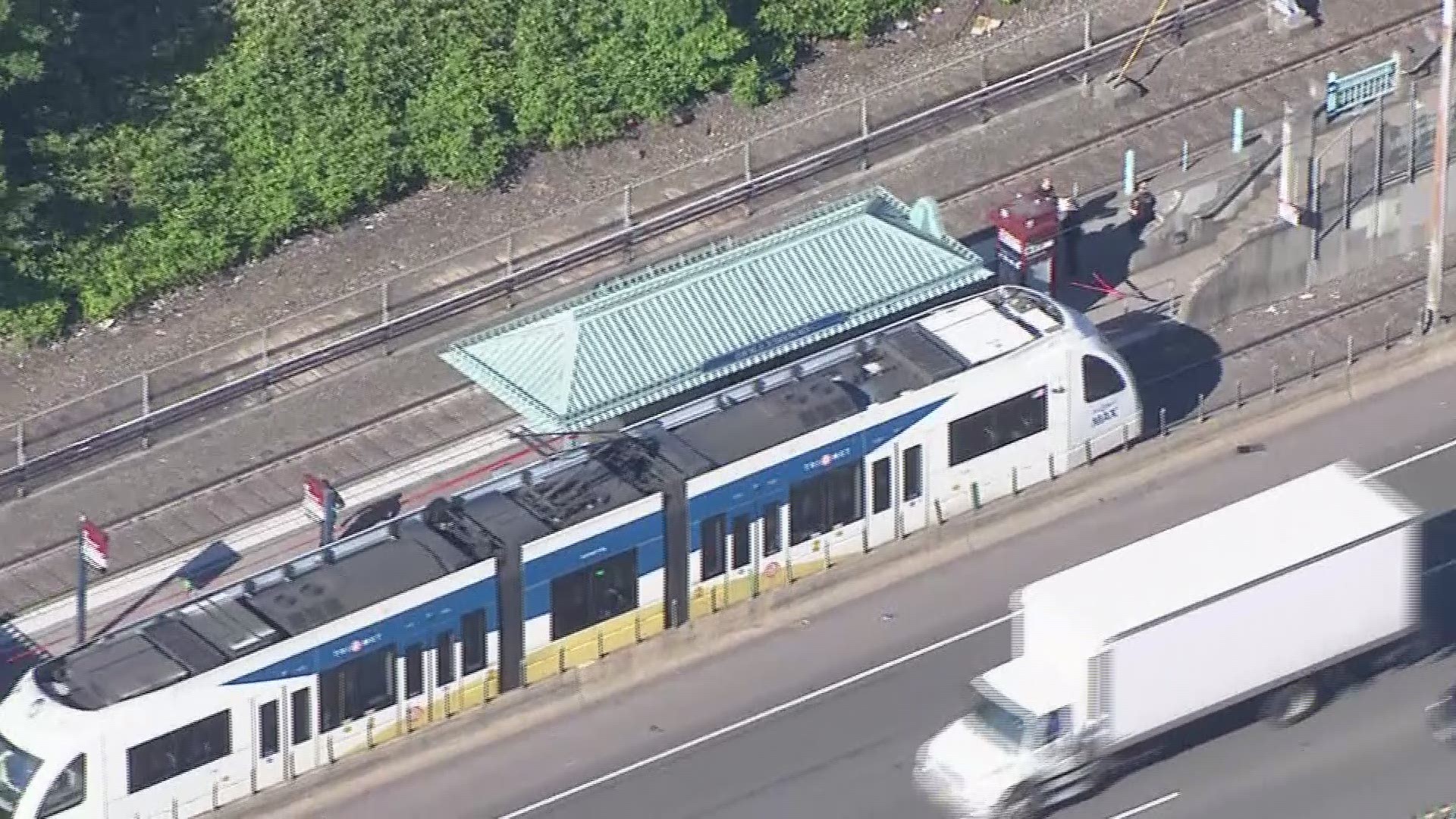

In early January 2020, the judge ruled she will allow jurors to tour a TriMet train similar to the one where the 2017 attack occurred, but isn't letting them see the actual train car where the stabbings occurred. The defense wanted Christian to be present that day during the trial but the judge denied that motion.

Hate crimes and extremism in Portland Chapter 5

In the months leading up to the stabbings - and after - Portland seemed to be a hotbed for extremist protests and rallies.

The rallies, often held downtown or near the Portland waterfront and heavily publicized among activist groups, pitted self-described far-right protesters from across the country against those who called themselves anti-fascists. The rallies painted the Rose City, much to the chagrin of many local civic leaders and groups, as a focal point for violent, political brawls on a national scale, and led to dozens of arrests.

The rallies began shortly after the 2016 presidential election and continued into the summer of 2019.

Political analysts have meditated on why Portland became a battleground for white supremacists and extremists, and the answer could be said to stem from the state's racist past.

When Oregon became a state in 1859, it forbid black people from living in the state. And the state refused to sign on to the 15th Amendment that gave black people the right to vote until 1959, nearly 90 years after it was ratified, making it a destination for racist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan.

In response to increased attacks by groups of white supremacists in Portland, the state passed a hate crime law in 1981, that charged perpetrators with intimidation, a misdemeanor. If two people were involved in carrying out the crime, it could be elevated to a felony.

One of the most high-profile hate crimes in Oregon was the murder of 28-year-old Mulugeta Seraw, an Ethiopian student who moved to the U.S. for college.

Seraw was beaten to death by a group of three white supremacists, and his attackers were charged with felony intimidation because they acted as a group.

Thirty-six years later, Christian's alleged violent rampage has in fact only led to one hate crime charge - two counts of intimidation for his behavior toward the two black teenagers on the MAX train. His murder and attempted murder charges do not fall under the hate crime statute.

The intimidation charge is a misdemeanor, a sign to some observers that Oregon's hate crime law is behind the times and in need of an update.

“It reflects a bit of a bygone era when hate violence was thought to be orchestrated by organized groups," Brian Levin, the director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino told the New York Times.

Oregon legislators updated the state's hate crime law in 2019, motivated by another high-profile killing of a black man, Larnell Bruce Jr.

The new law established hate crimes as felonies, created a hotline for victims to call, and changed how hate crimes are reported and tracked.

It's unknown precisely how much hate crimes have risen in Oregon year to year because many go unreported. The FBI keeps track of the reported cases, which show a clear uptick in 2016 from years prior:

- 2018 - 118 crimes

- 2017 - 146 crimes

- 2016 - 104 crimes

- 2015 - 56 crimes

- 2014 - 26 crimes