Jury selection, defense strategy: What to expect during the Jeremy Christian trial

KGW is working with three experts to analyze what we should expect in the coming weeks as Jeremy Christian, the man accused in the MAX stabbings, goes to trial.

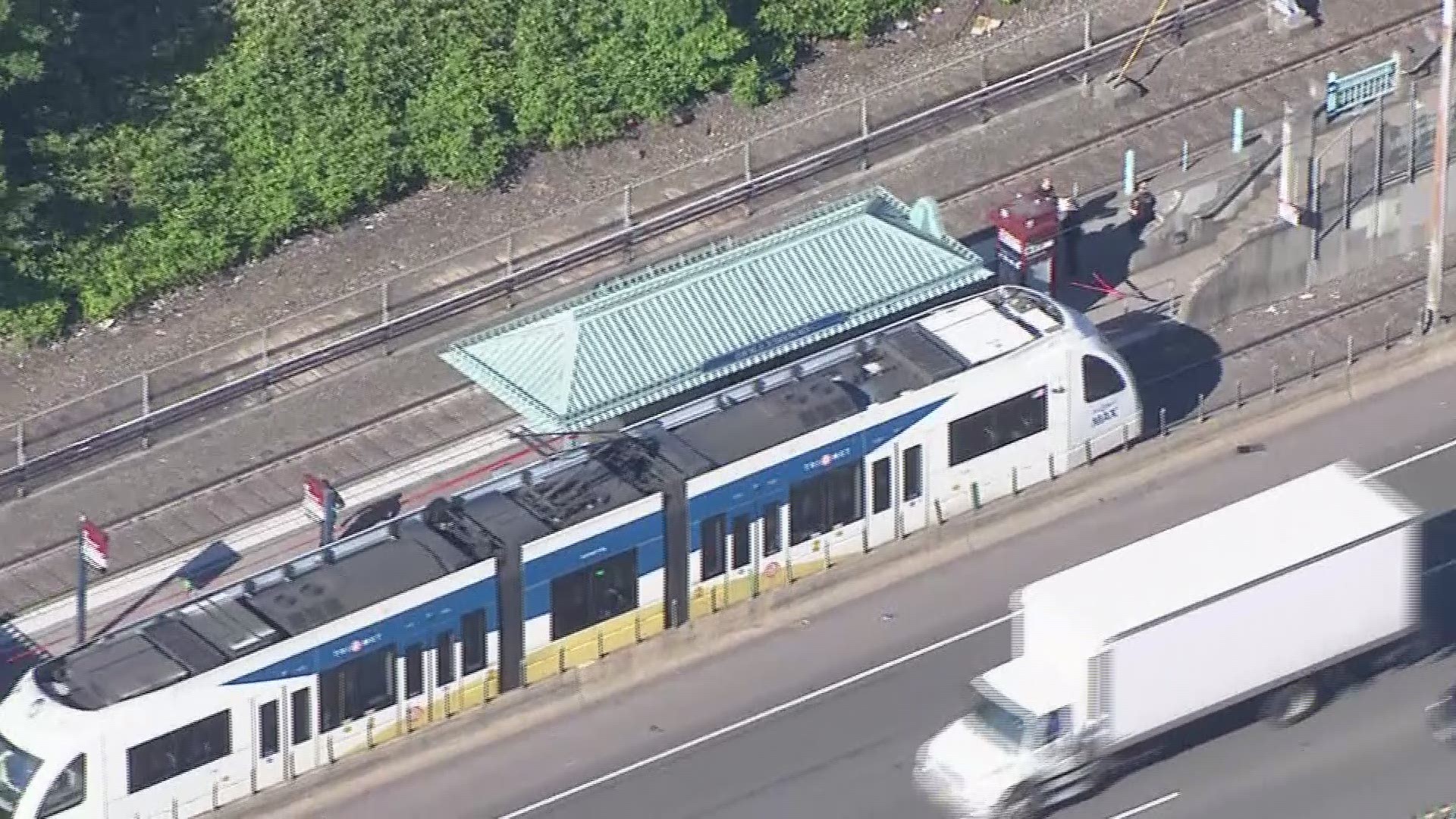

Jury selection begins this week in the double murder trial of Jeremy Christian, a Portland man accused of boarding a crowded MAX train in May, 2017 and aiming a racist, hate-filled rant at two black teenage girls, one of whom was wearing a hijab.

He’s then accused of stabbing three men who intervened or stood nearby.

Two of the men, Ricky Best and Taliesin Namkai-Meche, died. The third, Micah Fletcher, was gravely wounded but survived.

Christian faces a long list of charges, including two counts of first-degree murder and one of attempted murder.

Christian has admitted to carrying out the stabbings, but has pleaded not guilty by reason of mental disease or defect, and according to a psychological evaluation requested by his attorneys, he claims he was on “auto-pilot” during the incident and “feared a physical attack” by the men.

In the years since, his attorneys fought successfully to eliminate the possibility of Christian being sentenced to death, by getting his two murder counts reduced from "aggravated" to "first-degree."

They also moved to have the case relocated out of Multnomah County, arguing that local press coverage would thwart Christian’s chances of receiving a fair trial. Judge Cheryl Albrecht denied that request, and the case will remain in Portland.

Opening statements are expected to begin Tuesday, Jan. 28.

In preparation for what’s expected to be a month-long trial, KGW has acquired the help of three local attorneys, retired and practicing, to offer expert analysis on arguments, motions and decisions made.

None of these analysts have worked on the Christian case, nor have they communicated with anyone involved in it.

Meet the experts Chapter 1

BOB WEAVER

- 45 years experience as a trial lawyer, working both as prosecutor and defense attorney; currently with Foster Garvey PC

- Former assistant U.S. Attorney in charge of the criminal division for Oregon

- Investigated and prosecuted the Rajneesh cult (as a result, was featured in Netflix’s documentary "Wild Wild Country")

- Represented Tonya Harding following the attack on rival skater Nancy Karrigan

STACY HEYWORTH

- 31 years experience as a Multnomah County prosecutor (now retired)

- Tried “many” murder cases, including death penalty cases

- Led the Domestic Violence Unit, the Career Criminal Unit, the Gang Unit and the Pretrial Unit

LISA LUDWIG

- 24 years experience as a criminal defense lawyer

- Currently with Ludwig Runstein, LLC

- Has tried cases in state and federal court, with charges ranging from assault to aggravated murder

Choosing a jury Chapter 2

Jury selection begins Tuesday, following years of intense media coverage examining the stabbings and Christian himself. In a case like this, is it difficult, or even impossible, to find truly impartial jurors?

Weaver: I mean, there's no question that probably 99% of this jury pool will have seen, heard or read something about the case, but the test is whether or not they can put aside anything that they may have read, heard and seen and judge the case solely on the evidence that's produced during the course of the trial and follow the directions on ... what law applies to this case. There are a number of counts in the case, so I think it's possible to get jurors who are able to do that. A lot of it's going to depend upon the relationship that the judge in this case, Judge Albrecht who is an excellent judge, [has] with those jurors. Because I think particularly in long cases, jurors come in, and they're a little wary of the lawyers. But they really have a tendency to bond to the judge and to rise to the occasion to do what's the right thing to do.

Heyworth: I think a lot of the people might just say they can't be on the case because of the type of case that it is. I've had that happen in other aggravated murder trials where people are just far too upset about the facts that they choose not to be on the jury, and if they say that they can get off of the jury very easily because it can't be fair. And I suspect that a number of people are going to say that in this particular case.

Ludwig: I think that, in some ways, we don't give jurors quite enough credit. I mean, they take this job, in my experience, very seriously. And you know in this day and age, people are pretty sophisticated. I mean, it's not Walter Cronkite telling it to you anymore, you know, the one authoritative source of information. It's a lot of disparate sources of information, and people can kind of pick and choose what they listen to. So the first thing is, I'm not sure that you should expect that all the jurors in the panel have been exposed to media about this because that's not a guarantee. But even if they have been exposed to some media, it hasn't necessarily created in them a fixed and unmovable opinion about what took place.

What kinds of questions would you be asking potential jurors, and what qualities would you be looking for?

Weaver: You will want to question any juror who says that they can be fair to see whether or not there's an attitude or hidden bias that might about that kind of a thing that might prevent them from being fair. And at this stage… the evidence hasn't come in. So the lawyers have to cautiously describe or anticipate what may be coming in as evidence and not and direct their questions based upon that… I think the questions will go to the threshold of explosive answers in certain cases with certain perspective jurors, and this judge may need to take that a juror with the lawyers in camera to do an in camera review. So whatever that juror says in response to those questions is not heard by everybody else. So for example, if in response to a question, ‘What have you seen on KGW about this case?’ And a juror says something that sounds very prejudicial, then if those other jurors haven't heard that [on KGW], there's now a problem created by that answer with these other perspective jurors.

Heyworth: As an ex-prosecutor, I would want some intelligent people on there because indeed, if this "guilty except for insanity" case comes up, you have to parse through the law in order to determine whether or not that's an accurate defense or a viable defense… I would just want average Americans because those people know what it's like to live an average life. And they also watch television. They do all sorts of things… where they have seen things on the news about people who act in a vicious manner, and I suspect that that's not going to cause most people to want to disqualify themselves because we see all of this stuff in the media all the time.

Ludwig: Well, obviously questions about their exposure to individuals with mental health problems… People who've been incarcerated, people who've been in any kind of institutional setting, people who suffer from paranoia or distorted perceptions… and whether they believe that those people should be able to express those beliefs despite the fact that they're repugnant.

"Guilty except for insanity" defense Chapter 3

What's your take on Christian’s “guilty except for insanity” defense, and which factors tend to be especially key in that strategy?

Weaver: As I understand it, there will be some defense presented here that would really be the equivalent of trying to establish a severe emotional disorder that provoked Mr. Christian to attack the three people that he attacked. And it's going to be interesting to see if that's the case and if the defense lawyers are going to do that, whether that's going to be presented as a defense to the charges or in some way to obtain an instruction on a lesser included offense. So for example, the difference between first-degree and second-degree murder is that someone committed to the act under a severe emotional disorder, And if that's established, then you are entitled to an instruction to the jury of second-degree murder and you would be allowed to argue in front of the jurors that because of this, maybe he's guilty of something, but it's not first-degree murder.

Ludwig: When you're trying to, to demonstrate, for example, a “guilty except for insanity” defense, you look at of course the incident itself [and] add to that the previous conduct: his kind of prior environmental circumstances. Eight years of incarceration is significant. And if a lot of it was spent in solitary confinement, that's very significant. And then, you know, whatever other information is available. I suspect there's probably something out there about his mental health that will come out during the trial, and then they would certainly do testing and that sort of thing. But if an expert witness says that either his capacity was diminished or he was literally unable to appreciate the nature of his conduct, then you've met that burden.

Heyworth: I think the one thing that's probably going to require significant attention by the jury is, you know, the definition of “guilty except for insane”… I think people get it wrong frequently. An individual has to be essentially impaired. They have to qualify for an accepted mental health defense like schizophrenia, Schizoid Personality, all sorts of things. There are a number of certain psychological problems that would fit in that care category, but they have to show that particular defense is viable and that the person either couldn't appreciate the criminality of their conduct or couldn't conform their conduct to the requirements of the law… I think people have this sort of notion that because people engage in behavior that the average person would not engage in, that they're mentally ill. Really what it means is that they can be an angry person, a person riddled with a personality disorder. Those are people who continue to engage in antisocial behavior for much of their lives. And I suspect that's going to be what the state's expert is going to say… you know, in reading some of the things from the press about his conduct and also seen some clips on news briefs, I don't see him as somebody who is up there in the high end of any type of mental disorder. I see more of a personality disorder, which does not mean insane. It actually in the statute says it's not insane. You can't use that as an insanity defense.

Judge's rulings so far Chapter 4

Christian’s defense team tried to have the case moved outside of Multnomah County, arguing, because of local media coverage, he couldn’t receive a fair trial here. How often are motions like that granted? And how effective would a move like that be, given the geographical reach of modern media?

Heyworth: I think that the media coverage in Portland is media coverage that's used throughout the state. This case has garnered so much media attention that, you know, you could send this case to Lincoln County and they would know as much as people in Portland know about it. It can't go to a different state. It has to be within the actual state in which the crime occurred. But it is so difficult to get a change in venue. It very, very rarely happens… I'm not sure that it ever happened during my time in my 31 years and three months of experience.

Ludwig: I think there are probably certain types of cases where it's so local… It's like, you know, if someone blew up the courthouse. There would be no way to separate the location from the conduct, and if the people involved were closely tied to everybody in the community, like a public figure or something like that… But for most cases, change of venue motions are so rarely successful there. And the hard part is, is that you really don't know how biased your jury panel is until you are in jury selection talking to them and asking them questions and finding out. And so it's kind of a chicken and egg thing.

The judge has decided jurors will be able to visit a MAX car identical to the one where the stabbings happened. How common is that, and what kind of impact does it have?

Weaver: It's not granted routinely, but in a case like this, I think it's important to both the prosecution and the defense. So what's the point of it? As I understand. there's going to be evidence about the conduct by Mr. Christian as well as conduct by other people, including the deceased's, who confronted him as he was, as is alleged, intimidating the two African American young women. So where people were standing in relationship to him, where the door was, where everybody was is going to be important to the issues of intimidation and menacing. And if there is a self-defense in this case, it's going to be important to that, too.

Heyworth: I've done some walk-throughs, and typically the walk-through is done without anybody saying anything. The judge might point out an area maybe where the bodies were found or something like that. But the prosecutors don't talk. Defense attorneys don't talk. Only the judge will say something… And it can be extraordinarily useful. I tried a case against a man by the name of Michael McNeely and he brutally raped, assaulted a woman over several days and then threw her body in a dumpster up there, Forest Park, and lit her on fire… We did a walk-through of that scene, and it's just this little berm above St. Helens Road. And I watched the jurors. I kind of sit back and watch the jurors, much like the judge did, and it had a huge impact. People, you know, were fine on the bus on the way there, gabbing away. And boy when you got them up there, it was complete stone silence… it's such a big part of the murder. Why shouldn't it be a big part of the juror’s experience?

Defense strategy Chapter 5

Jeremy Christian has admitted to carrying out the stabbings. He’s also no longer facing the possibility of being sentenced to death. What are defense attorneys aiming for in a case like this?

Ludwig: In a case where a person is charged with a double homicide and death is no longer an available penalty, what you're thinking about is, is this person not guilty at all because he was legally justified in acting the way he did in response to what other people were doing? In which case, you know, he should be found not guilty. Or was he impaired to the point that he couldn't make decisions for himself or make decisions about what was going on around him that were rational? In other words, is he not guilty by reason of insanity? Or is it a situation where his mental state impaired his ability to judge what was really going on, in which case he might be guilty of manslaughter, which is a lesser offense. And the penalty for two manslaughter [charges] is very different from the penalty for two murder in the first degree charges.

Because the crime was so public and Christian has been caught on camera making threats and racist statements, outside observers might expect this to be a “slam dunk case” for the prosecution. What’s your reaction to that?

Ludwig: I don't think there's any such thing as a "slam dunk" anyway. I mean, I've explained it before as it's like a football game. You know, the Super Bowl's is coming up, and you can know everything about your team. You can know everything about the opposing team, you can do the research, you know about the conditions on the field, but it's a dynamic conflict, and you cannot 100% know what the outcome is going to be because it's happening in real time. I don't really believe there's any such thing as a slam dunk. I mean, having done this this long… Yeah, I don't agree with that.

Heyworth: I've had some slam dunk cases, and I know that some of the jurors might have thought, ‘Why is this going to trial?’ But we have a Constitution that says that defendants have a clear right to a trial, and, you know, in this case, he's going to be asking for the insanity defense or self-defense. And because of that, the jurors would not know about that sort of information pretrial. So it's important for that trial to go forward because they should be listening to all the facts of the case. But yeah, there are a number of times when I've prosecuted cases where it's been a slam dunk, but somebody wished to test the jury, and they have a right to do that.

Media's impact on the trial Chapter 6

Though live streaming will not be permitted, the judge is allowing one television camera in the courtroom, with a microphone placed on the witness stand. In your experience, what’s the impact of media presence?

Weaver: Well, I can tell you whatever small thrill a lawyer initially feels when they see their name in the paper associated with a big case evaporates in about 24 hours and gives way to a persistent sense of annoyance by all the media attention. It at best distracts you from your preparation, and at worst it, might report facts or circumstances that would prejudice your client's ability to get a fair trial. And that kind of reporting… it is not always just reporting things that are false, but reporting anticipated evidence in a way that does not present the other side of it. So you're constantly worrying as a lawyer in these circumstances, "What is out there that is going to prejudice my client's right to get a fair trial? What are these perspective jurors likely to see?"

Heyworth: I don't think it had any impact on the decisions made because you're so full-focused in what you're doing as an attorney. It just wouldn't interfere. For the witnesses… [they] could be very startled by the fact that the press was there. There are the nuts and bolts of preparing your witnesses for virtually anything. I never would say much other than, "Look, the camera's going to be there. Just pretend like it's not going to be there." So it really was not a very difficult thing to express to a witness or to a victim.

Ludwig: I would say my experience has been that the first day or so that there's media present… People notice it, and they might, you know, kind of focus on it, and after a while they forget all about it, and they don't even notice anymore… In general, I think that having a high profile trial might just make everybody, you know, work a little bit harder to do their best work. I mean, I was involved in the Bundy trial three years ago, and the media had a lot of interest in that case. I thought the lawyers and the court and everybody did some of their best work. You know, they rose to the occasion. And so I like to think that that's the ultimate effect that sunshine has on the process.

What to watch for Chapter 7

Final thoughts or factors to watch?

Weaver: I think there are some very interesting evidence questions that lie before this that are still unresolved in this case, as best I understand it now. I have not spoken to either the prosecutors or the defense lawyers in this case. So I'm only gathering what I can from the public record. But there were statements that Mr. Christian has been alleged to have said that are of an offensive racial nature. Whether those come in or not, I think, is going to be an important decision in the case. I think that, frankly, the most important part of this case is going to be jury selection and what occurs by the defense lawyers and the prosecutors during that selection process is probably going to decide, I think, they have a lot to say about the outcome of the case.

Ludwig: I think the government is going to lean hard into, you know, his repugnant beliefs. They have a really strong case that he had really repugnant beliefs, and it's a narrative that's very compelling, Right? I mean, it has a lot of emotional impact on everyone that hears it, that, you know, he was this racist who was targeting these blameless girls who were just trying to ride the train home. And the good Samaritans got involved. I mean, that's a powerful narrative, right? But it's a narrative ... about things outside of the facts that need to be decided in this trial. It might be an important commentary on what's going on, on a larger level in our community.

Heyworth: I'm interested in how the whole defense of “guilty except for insanity” is going to proceed. That one, to me, is an interesting, an interesting area of this case. I have done a number of those types of cases in the past myself, including the KOIN tower, Jimmy Rinker case that involved probably 10 psychiatrists. So I'd be interested in seeing how people cross examine those psychiatrists and what those psychiatrists testified to me because if that really is a defense that the defense is going to put on, it will require a number of people to testify. And I know a lot of those people who work in the field of forensic psychiatry, forensic psychology. So I'm kind of interested in seeing what they have to say.