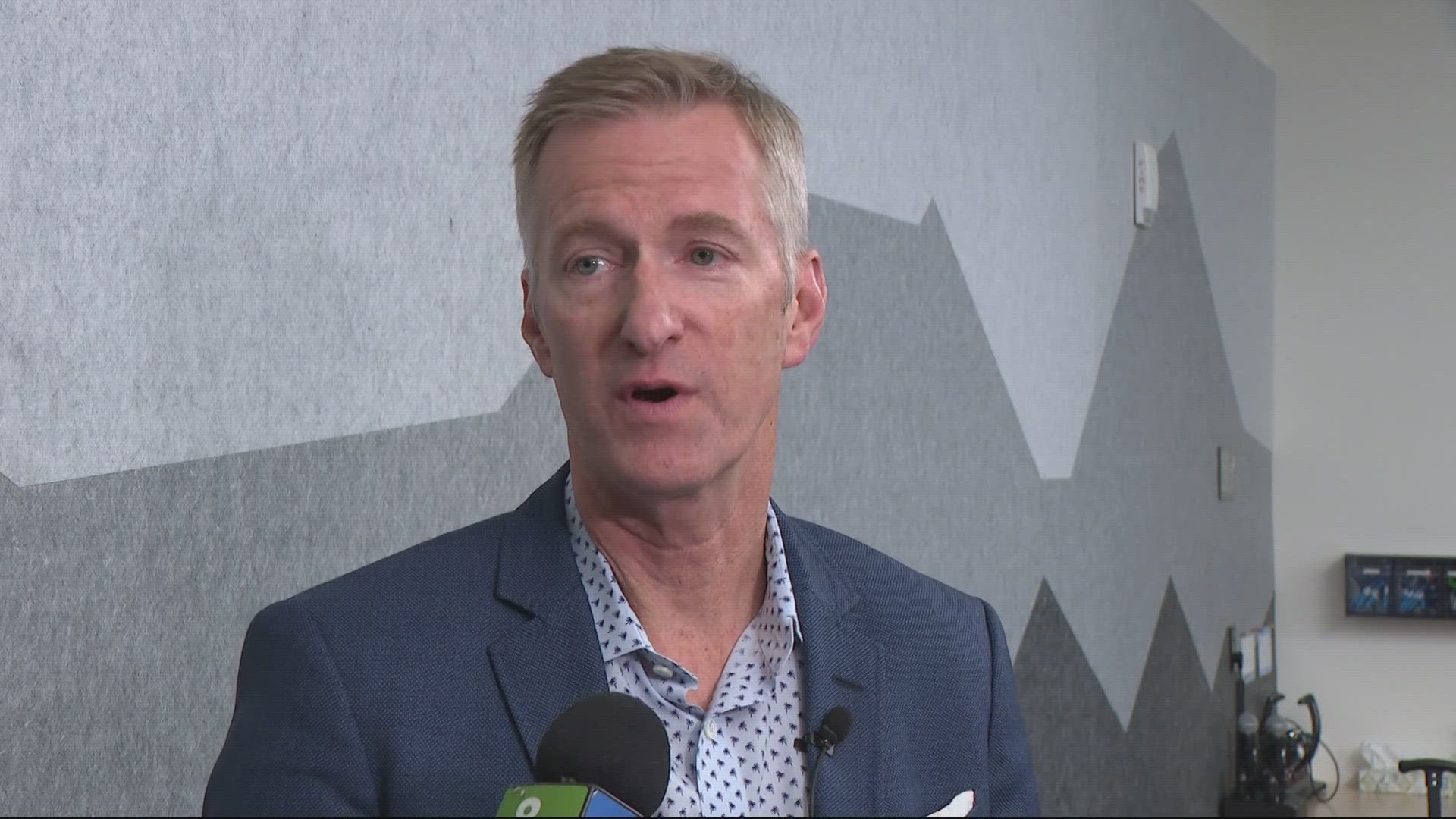

PORTLAND, Ore. — Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler has introduced a new plan for cracking down on homeless camps as an alternative to the city's current daytime ban on homeless camps, which remains on hold indefinitely while it makes its way through the courts.

Broadly speaking, the newly proposed ordinance would allow the city to punish homeless campers with fines or jail time if there is shelter space available and they refuse to accept it — closely tracking the letter of influential court decisions at the federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Two opinions, one of them stemming from the southern Oregon city of Grants Pass, currently restrict how municipalities in the western U.S. can enforce camping ordinances, requiring that there be shelter space available before someone receives criminal or civil punishments for sleeping outside.

RELATED: Oregon town lays out argument to US Supreme Court in case that could empower homeless camping bans

"The City Attorney’s Office believes these new proposed regulations would survive a legal challenge while providing the City the tools to change the status quo in Portland," said City Attorney Robert Taylor.

The new proposal from Wheeler's office hinges on the availability of "alternate shelter," which the ordinance gives a relatively broad definition and would include congregate shelters. Those shelters tend to have availability that varies by the day, since people seeking overnight accommodations usually have to get their name on a list to reserve a spot for each night.

"I want to be clear, this time, place, manner ordinance is a sliver of a much larger strategy to address homelessness in the city of Portland," Wheeler said Thursday. "Our primary strategy is to provide alternative shelters to reduce the reliance on unsanctioned camps on our streets as … My goal is to ultimately have no unsanctioned camping on our streets."

Under the new proposal, camping on public property would be illegal if the person has access to alternate shelter, or has been "offered and rejected reasonable alternate shelter." It's unclear how the city would determine the availability of shelter space throughout the city at any given time, which has historically been a challenge to accurately account for.

Congregate shelters are also particularly unpopular among many of Portland's unsheltered homeless residents, who cite the risk of theft or assault, lack of privacy, rigid hours, inconsistent availability, and rules prohibiting pets, weapons or drug use. City surveys have borne out that a number of homeless Portlanders prefer to camp outside, which Wheeler has cited as one motivation for the construction of larger outdoor shelter spaces like the Temporary Alternative Shelter Sites.

But even with these overnight shelters as an option, Wheeler acknowledged Thursday that the city does not have enough shelter space at present to provide beds for everyone.

"The truth is, we do not have enough shelter beds for every single person who is counted as homeless," he said. "And so, what this ordinance makes very clear is if we do not have adequate shelter available, then we cannot enforce either the fines or the potential jail sentence that comes with this ordinance."

On top of shelter-dependent enforcement, the ordinance would add that it is illegal to camp at any time in a way that obstructs a pedestrian use zone, restricts access to private property or blocks businesses next to the public right-of-way. Cook fires, gas heaters or anything approaching permanent structures would also be banned.

The ordinance likewise bans behavior that causes any environmental damage around a campsite, storing objects more than two feet outside a tent, accumulating debris or garbage, and accumulating vehicles, bikes or parts of either.

Violations would be punishable by a maximum fine of $100 or 7 days in jail — a much-streamlined penalty structure with lower consequences compared to the previous ordinance. The proposed ordinance also encourages the Multnomah County District Attorney to divert these criminal cases for "assessment, emergency shelter or housing, or other services" instead of seeking convictions.

"The goal is not to lead with law enforcement, it is to lead with a compassionate approach," Wheeler said. "It also does give us law enforcement tools, but those tools are contingent upon us having shelter space, and contingent upon people minding, if you will, the manner restrictions that are written into the ordinance."

City commissioners approved the existing daytime camping ban in June of last year, but pledged to delay enforcement until the fall to allow for several months of "education and outreach." Just days before enforcement was set to begin in November, a Multnomah County judge called a halt in response to a class action lawsuit filed on behalf of homeless Portlanders. The case has yet to go to trial.

That ordinance — still technically on the books — banned camping full-time in parks, along high-crash corridors, and near schools and shelters. It also banned camping on all public property between the hours of 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. While violations of the ordinance likewise offered a potential fine of $100, they also carried a maximum sentence of 30 days in jail after several warnings.

Wheeler's office argues that the city of Portland may be obligated to take up a new ordinance, since a state law passed in 2021 required that cities align their camping ordinances with state requirements by July of last year. The daytime camping ban was ostensibly the city's effort to comply, although the class action lawsuit filed last year alleges that Portland's ordinance violated that very state law.

"I do not think that the public is going to see a dramatic change in appearance based on this particular ordinance," Wheeler said of the new proposal. "The public is already noticing an improvement — they are already seeing the difference because of the increased shelter opportunities, the increased services that we have been providing, the partnerships that we have been developing, the outreach that we have been creating with the homeless population."

This new ordinance is expected to go before Portland City Council for a first reading on Thursday, April 18, according to a release from Wheeler's office. It could come up for a vote by the following week.