PORTLAND, Ore. — Despite a record number of people living in tents and RVs throughout Portland, hundreds of the city's shelter rooms and beds aren’t being used.

In June, publicly supported shelters in Multnomah County had an occupancy rate of 81%, according to data from the Joint Office of Homeless Services. The county has a total of 1,402 shelter units, which means on any given night, roughly 264 spaces are vacant.

“I don’t want to go to a shelter,” explained Dave Cooper, an unhoused Portlander who sleeps outdoors at Sewallcrest Park in Southeast Portland or other public spaces.

Cooper said shelters aren’t a viable option because of concerns over privacy, personal safety and a strict curfew.

“I couldn’t do it,” said Cooper, sitting next to a shopping cart filled with his sleeping bag and other belongings. “Being out here, it’s freedom.”

Shelter vacancies

Publicly funded shelter beds can include both traditional congregated sleeping spaces and alternative unit styles such as tiny homes or converted motel rooms.

In June, thirteen shelters in Multnomah County had occupancy rates below 75%. Walnut Park had an occupancy of 55%, which means on average 27 of 60 available beds were not used on any given night at the Northeast Portland shelter.

Arbor Lodge Shelter, operating out of a former Rite Aid in North Portland, had an occupancy rate of 64%, meaning 25 of 70 units weren’t used.

“Ideally, we’d like shelters to be at 100% utilization. We also realize that is not going to be the average,” said Shannon Singleton, interim director of the Joint Office of Homeless Services.

Some beds might sit empty because they’ve been reserved for the night and the person didn’t show up, Singleton said. Many shelters operate on a reservation system, similar to a restaurant or hotel.

“This system means if we put somebody on a waitlist, they get assigned a bed. We give them time to show up. There are going to be nights when a bed is assigned to somebody, but they may not show up,” she said.

For many years, homeless shelters required people to line up for a bed each night on a first come, first served basis. That system has been phased out because it was deemed inequitable and unfair, Singleton said.

“A lot of people who were more vulnerable, maybe had disabling conditions, didn’t get a bed because they weren’t able to push to the front of the line,” she said.

Homeless residents skeptical

Many people experiencing homelessness have expressed skepticism about the shelters.

“I have not been in a shelter since a warming shelter four years ago, when it snowed so hard,” said Timothy Varner, who has been sleeping outside in Portland for 15 years.

“I prefer to be outside because that way I can get up and move,” Varner said, while resting in the grass at Sewallcrest Park. “I can sleep in a nice area.”

A 2019 survey of 180 people experiencing homelessness in Oregon, conducted as part of an Oregon Statewide Shelter Study by Oregon Housing and Community Services, found that the top barriers for using shelters were personal safety and privacy concerns, restrictive check-in and check-out times and overcrowding and unsanitary conditions.

A 2017 KGW investigation titled “Tent City, USA” identified similar concerns, including worries about shelter conditions and rules. A KGW survey of 100 people living in tents in Portland found 89% would rather stay in a tent over a shelter.

Michael Brunner’s sprawling tent encampment sits next to Edwards Elementary in Southeast Portland. The 54-year-old Portlander said he prefers living in outdoor conditions, even during the cold, wet winter months.

“I think that shelters are too temporary and there’s too much stimulation. I’m high functioning autistic. I just couldn’t. It’s not something for me. There’s too much going on,” he said.

Oregon ranks comparatively high for shelter occupancy rates

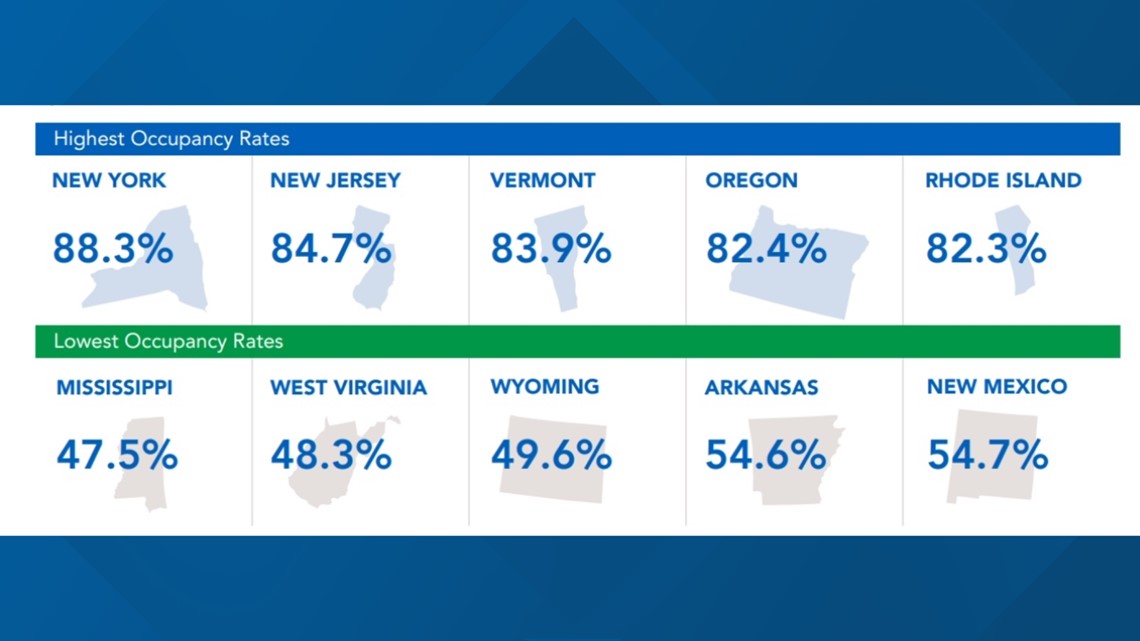

In 2021, Oregon had one of the nation’s highest shelter occupancy rates at 82.3%, behind New York at 88.3%, New Jersey at 84.7% and Vermont at 83.9%. All five states with the highest occupancy rates on the night of the point-in-time count were in colder climates.

Nationwide, the number of shelter beds remained relatively flat between 2020 and 2021, although occupancy rates declined. 73% of shelter beds were occupied in 2021, down from 82% in 2020, according to a report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Making shelters more appealing

Community leaders and advocates have pushed to increase the supply of shelter beds for people experiencing homelessness in Portland.

In June, Multnomah County approved a $3 billion budget for fiscal year 2023, including $130 million for shelters and outreach to support over 2,000 beds of year-round adult shelter services.

Advocates admit creating more shelter beds doesn’t automatically mean people will use them. Instead, the government and non-profits running shelters need to make them more accommodating. Many shelters allow pets, allow residents to stay for extended periods of time and let them securely store their belongings during the day.

Instead of large rooms, where people sleep on cots or mats, many congregate shelters now have rooms divided by private bays and offer spaces like kitchens, bathrooms and laundry rooms.

Multnomah County also has a variety of alternative shelters, including private sleeping pods.

The Kenton Women’s Village offers small sleeping pods — each is roughly the size of a household shed — for 20 women. The village offers a kitchen and shower facilities, water delivery and garbage pick-up, access to legal and financial services, along with mental health and physical healthcare.

In June, Kenton Women’s Village had 4 of 16 units utilized, or 25% occupancy.

“What we hope to really look at now that we have these multiple types of shelters is, what is the length of stay by different shelter type? What is the outcome by different shelter type? How many people go into permanent housing versus transitional or back to the street?” explained Singleton.

Several people experiencing homelessness told KGW there should be less emphasis on emergency shelters and more focus on affordable housing, mental health and drug treatment.

“I just think that if they focused more on prevention, instead of post — what do we do now, it could turn around. It’s the only way it could turn around,” said Brunner, outside his tent.

Housing advocates agree that shelters are only a piece of the puzzle in helping to curb homelessness.

“I think over time that is the goal. It is a system that is much more about keeping people in their affordable housing and our shelter system should start to shrink,” said Singleton. “We’re just not at that point.”