JOHN DAY, Ore. — The vast expanses of eastern Oregon represent a rural oasis from the urban sprawl found in much of the Beaver State's western half. For months, many residents in Oregon's eastern counties have been contemplating a divorce from the west via the so-called "Greater Idaho" movement. They're fed up to the point that they want to move state borders and become Idahoans.

Many of these eastern Oregonians feel that the lawmakers and state officials in Salem aren't listening to their grievances and don't care, but often that's all we hear — we don't hear why they're so unhappy. So The Story recently launched a listening tour throughout northeastern Oregon to hear from the residents themselves.

The trek took KGW's Pat Dooris to the small city of John Day and a conversation with the Grant County Sheriff, then to the property of a Union County rancher who recently lost his dog to re-introduced gray wolves, with a number of stops along the way. But not everyone he spoke to expressed readiness to say goodbye to Oregon.

So, what are the issues causing such a fractured state of mind? Could there be middle ground? That's what Dooris and his crew tried to find out.

'A whole different mindset'

Out in eastern Oregon, the Greater Idaho movement is no joke. Eleven of Oregon's 15 eastern counties have voted in favor of considering the proposal to re-draw state boundaries between Oregon and Idaho. If successful, it would make the majority of eastern Oregon part of Idaho.

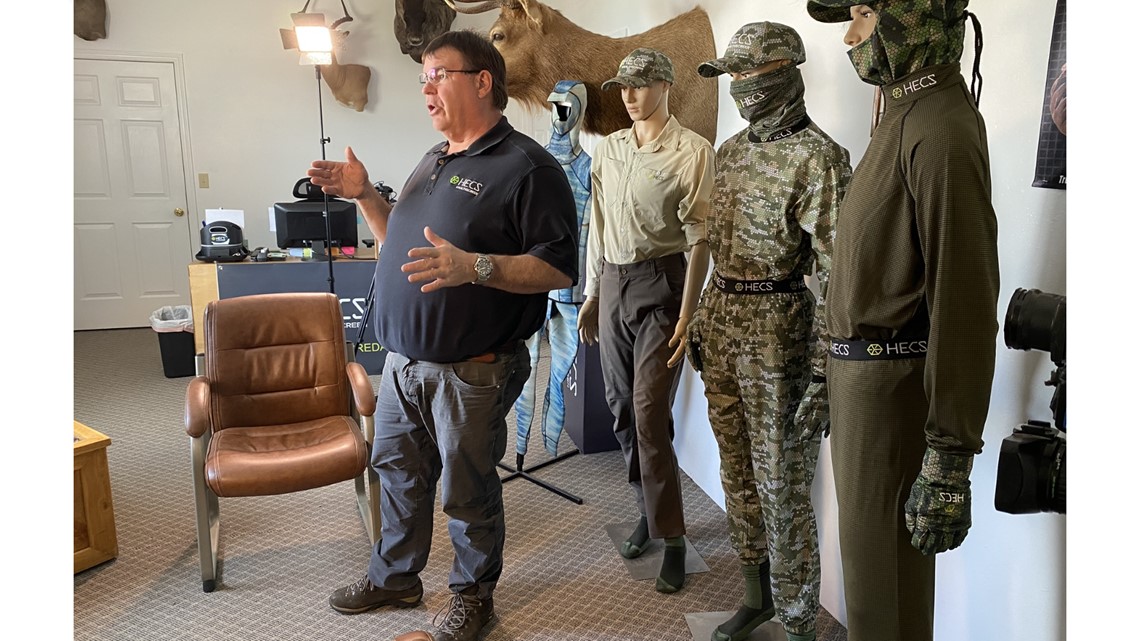

Mike Slinkard is a lifetime resident of Grant County. He's also an entrepreneur, and has his own bow hunting show that runs on cable channel.

"You know eastern Oregon’s filing for a divorce," Slinkard said, chuckling.

He's convinced that most who live in Oregon's big cities have no idea how different the culture is where he lives.

"What goes on here is night and day different than what goes on in Portland," he said. "It’s a whole different experience."

Slinkard's world headquarters are located on a bluff overlooking the town of John Day. The walls of his office boast trophy heads, animals he's killed as a bow hunter. He doesn't expect that urban viewers would understand.

"My grandfather and uncle actually were cattle ranchers in the Monument area which is north Grant County," he said. "And then my dad and his father were all loggers. So I’ve got both sides of the spectrum for eastern Oregon I guess."

Slinkard's a third generation Oregonian, he said. But when asked how he feels about the state these days, he got thoughtful.

"You know ... up until about 10 years ago I felt great about it. I was a proud Oregonian. Back in 2000, when I was starting my original business the state was actually very helpful," Slinkard said. "But now, to us, there’s a lot of craziness going on in the state. We’re getting laws passed that we don’t agree with. We feel like we really don’t have a lot of representation. We’re getting taxed way more than we ever have before. And as a business person it makes it very difficult to be located here. If I didn’t have my roots so deep in Grant County I’d probably already be in Idaho, to be honest with you. I have my elderly parents I’m taking care of here and things like that so … ”

Thirteen miles to the east of John Day sits the small town of Prairie City. Its only school houses kids from preschool through the 12th grade.

Many love the rural culture here. Teachers are understanding about kids showing up late; many live on ranches or farms and have morning chores, and sometimes the birth of a cow or goat makes them tardy.

And there are other cultural differences from the west side, urban schools. Here livestock, including the school's cows, are not pets.

"They know that those animals are going to go to a butcher shop — they know that someone's gonna eat them — so it’s a whole different mindset," said Amanda Rockhill. "As opposed to something you’d have in your backyard. It's just different.”

Rockhill is a teacher and leader of the school's Future Farmers of America program. Her students raise the school's cows and pigs.

"Its JC’s dad — the girl we just talked to," Rockhill said. "Her dad donated these hogs for our program. These two will be butchered and the meat will be going to our cafeteria for our entire school to eat."

One stoplight town

The differences between eastern and western Oregon are many. Locals say that everybody knows everybody else — which means you can't get away with anything unnoticed. Even on Main Street, you can leave your F-150 running with no one inside. In all of Grant County there is just one stoplight, found in the middle of John Day.

Cathy Gill is a server in town. She has a second job working with adults with disabilities. She loves her part of Oregon.

"I honestly feel we should just have our own eastern Oregon," Gill said. "When you come over to eastern Oregon people say, 'Oh! This is really pretty — it's Oregon.' No. We’re eastern Oregon. That’s where we’re at. That's what we call it. And its … God’s country. That’s what we’ve always called it."

Gill said that she's on the fence about whether she supports the Greater Idaho movement. Like many people KGW met, she says she's certain that urban leaders, including the governor, don't care about east side opinions.

"I think she should come and listen — and listen to everyone and get everyone’s opinions," Gill said. "But I don’t think it will change their mind. I don’t. I think they take care of the city people. The votes are there. You can see it. We don’t have much of a say when it comes to any part of voting."

Perhaps aware of the stark division in her state, Governor Tina Kotek announced a statewide listening tour shortly after the election, with the goal of hitting each county in the state within her first year in office. She just visited her fifth county, but has yet to venture east of the Cascades.

From a political perspective, Gill is correct that Oregon's urban areas tend to decide who will fill the governor's office and other statewide roles. During the 2022 election, Republican Christine Drazan got 3,145 votes in Grant County, or 75% of the total. Kotek got just 576 votes, or 14%. But the lopsided percentages don't matter much in the grand scheme of things. Oregon's blue counties, with their densely packed populations, overwhelmingly went for Kotek over Drazan.

In Multnomah County alone, Kotek received nearly 266,000 votes — far more than the entire populations of the eight counties that the Oregon Employment Department considers to be eastern Oregon. In total, those counties hold just 191,000 people.

For bow hunter Mike Slinkard and others like him, those numbers mean that Oregon passes statewide laws that make sense in the cities, but not in the country.

"We’re hard-working people. We use diesel trucks. It’s a long ways between places and we have to travel," Slinkard said. "And some of things coming down the pike would be hard to deal with — impossible to deal with out here."

He's referring in part to bills in the Oregon legislature that focus on diesel fuel. Diesel powers a lot of the pickup trucks on the east side, but also the farm and logging equipment. And it's a big target for people who want to cut carbon emissions and fight climate change.

Two of the three bills in question will not become law this legislative session, they simply didn't gain enough traction. But the third bill, Senate Bill 803, worries a lot of people out here. With a few exceptions, it would outlaw regular diesel statewide in Oregon, requiring the sale of renewable diesel only by 2030.

"We care about the environment as much as anybody. We live in it. We’re probably closer to the land than most urban people as well. So we care about it," Slinkard said. "But at the same time, you’ve gotta, you know, recognize cultural differences and recognize how people have to make a living in different places, you know?”

Is listening enough?

To these folks, Oregon feels like a marriage that has been in trouble for a long time.

"It really angers people, 'cause we’re just not listened to," said Cathy Gill. "They might come and visit and see it. But they don’t wanna solve the issues or the problems."

Slinkard isn't sure what Oregon leaders could do to make eastern Oregonians feel differently about the state of affairs.

"If there was something we could do I think we’d be trying to do it. And I’m not sure what that is," he said. "I think the divide just feels so huge ... it's just like, it's just like we don’t agree on what's white and what's red, almost. We can't agree on anything, seems like."

"If there was some effort ... I think our side would be willing to put forth effort, but right now we don’t feel like there's a reason for them to give effort, 'cause like I say it really is an 'us and them' thing."

Slinkard named some other things that he's angry about, including Oregon's capital gains tax, the passage of the gun control initiative Measure 114 and Measure 110, the initiative that decriminalized user amounts of drugs.

Whether they wanted to join Idaho or not, many of the people KGW spoke with expressed similar frustrations. It seemed to boil down to this: The culture is dramatically different in rural areas, and the people who live there have no political power to protect themselves from statewide laws that they don't support.

This story is part one of a series of stories on eastern Oregon. On Tuesday, The Story will take a deeper dive into the Greater Idaho movement, meeting the organization's vice chair, and explore the rural/urban divide.

- PART ONE: Eastern Oregonians say they've been ignored by state leaders for too long

- PART TWO: What's the appeal of 'Greater Idaho' for eastern Oregonians?

- PART THREE: Idaho isn't such a great idea for some disgruntled eastern Oregonians

- PART FOUR: 'We still have hope': Eastern Oregon sheriff isn't ready to endorse 'Greater Idaho' movement

- PART FIVE: Union County rancher describes the cost of living in Oregon's wolf country