PORTLAND, Ore. — Alzheimer's disease is a devastating yet common condition, made all the more painful by the fact that there's no cure and the disease is difficult to study. But after seven years of work, researchers at Oregon Health and Science University say they've discovered a new cause of Alzheimer's and vascular dementia.

"A big surprise, and we spent seven years doing this study because we had a hard time believing that the field as a whole, worldwide, could have missed such a significant finding," said Dr. Stephen Back, a lead researcher.

The study was published in the journal Annals of Neurology in August.

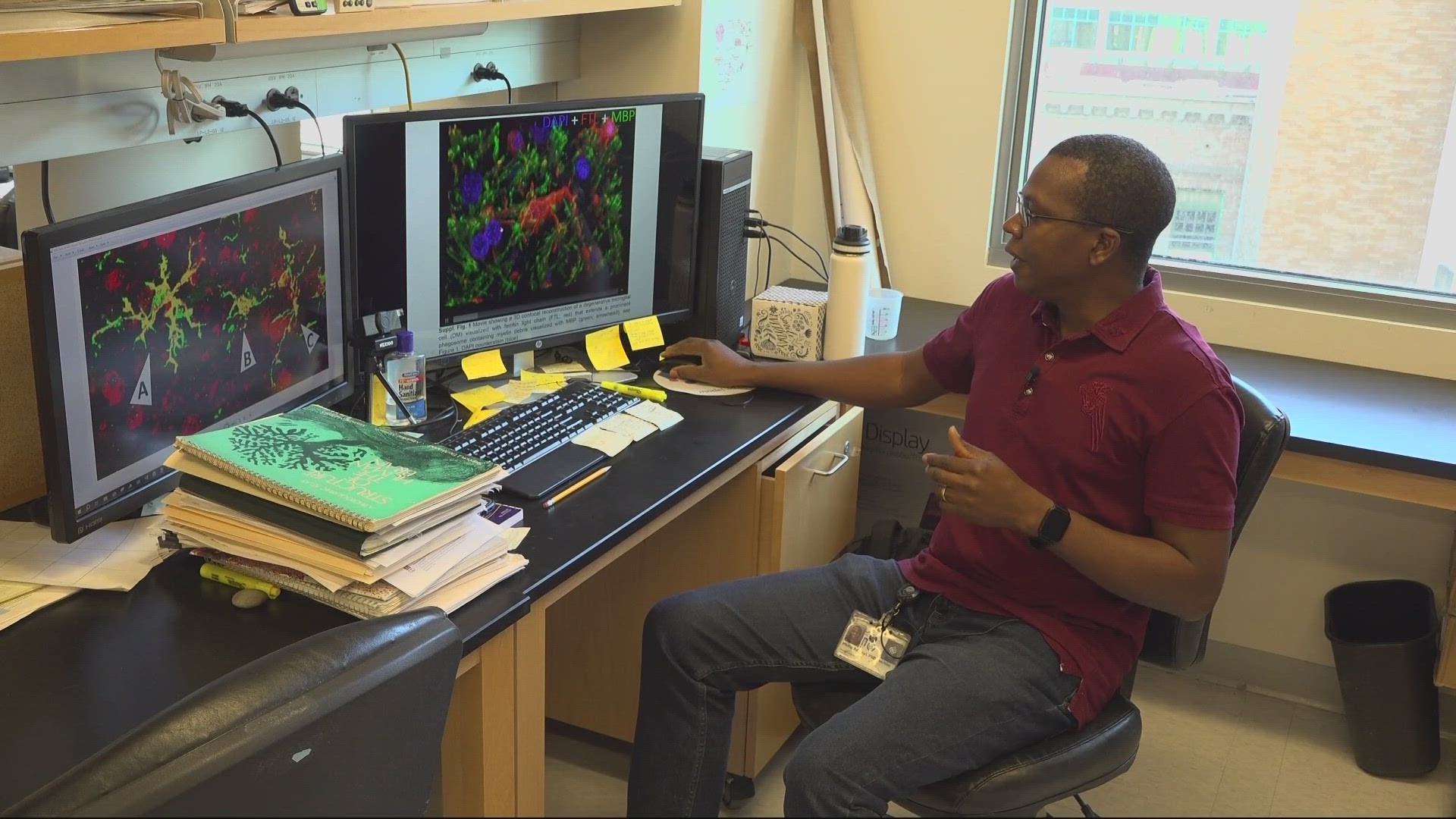

Back said it was one of the study's co-authors who first noticed unexpected activity in a sample of microglia cells in 2017. Microglia cells are involved in immune responses in the brain, clearing out cell debris. But the cells under observation didn't activate; instead, they were dying.

"[I] sat down at the microscope for a couple of days, studying all of the slides, and (the more I watched), the more astonished I was that yeah, she’s on to something here," Back said of the discovery.

The study examined post-mortem brain tissue of patients with dementia and found that the microglia cells had degenerated in the white matter of the brains of patients with Alzheimer's and vascular dementia.

One of the jobs of microglia cells is to clear out debris from damaged myelin, which is an insulation-like sheath around nerve fibers in the brain. The study discovered a form of neurodegeneration triggered by myelin deterioration, in which microglia cells swarm in to clear out iron-rich myelin debris, only for the microglia themselves to be killed in the process.

Back and his team could see that the microglia cells were being damaged by the excess iron, and once filled with iron, the cells began to die off. The cells were doing what they're supposed to do by clearing out the myelin debris, but they were essentially "dying in the line of duty," according to a news release from OHSU, setting off a cascading effect that appears to contribute to the progression of Alzheimer's and vascular dementia.

"Large numbers of these cells are just not available to do their job in the brain," Back explained.

Previous research hadn't uncovered the link between this specific form of iron-related microglia cell death — known as ferroptosis — and Alzheimer's. Back and his team conducted their study on human brains, and he said that's one reason why they were able to make the discovery.

"We had 40 of these brains that we studied to try to understand the range of responses that these cells might have," Back said.

Back said he expects these findings to inspire new pharmaceutical research aimed at reducing microglial degeneration.

"There are a whole class of new drugs that drug companies are starting to think about and develop to target these sorts of problems," he said.

He speculated that the underlying cause of the degeneration could involve periods of low blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain due to stroke, hypertension or diabetes.

"Dementia is a process that goes on for years and years," he said. "We have to tackle this from the early days to have an impact so that it doesn't spin out of control."