OLYMPIA, Wash. — It has been 320 years since the last major earthquake hit the Cascadia subduction zone. The Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) wants to help communities along Washington's coast prepare for the next one.

On Jan. 26, 1700, an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 9.0 struck the fault, causing the coastline to drop several feet and producing a tsunami that crashed onto land, leaving sand deposits and drowned forests.

Geological evidence shows these large quakes happen about every 250 years, which means one could happen at any time.

The DNR wants Washingtonians to be able to visualize what another tsunami could do to the state.

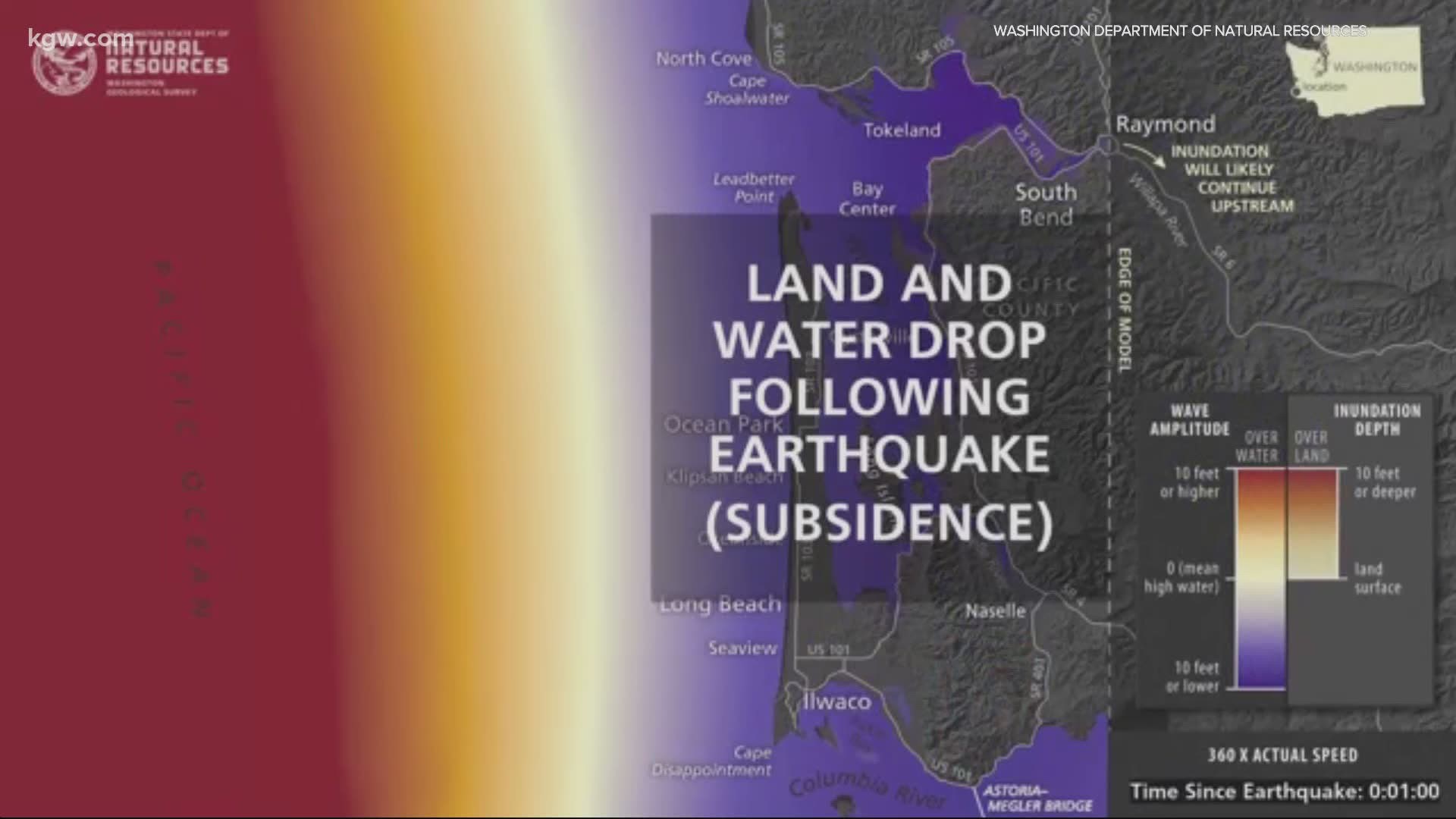

The department released a series of tsunami simulation videos that show the estimated height and speed of waves that would strike the southwest Washington coast following a magnitude 9.0 earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone. Geologists at DNR, home to the Washington Geological Survey, produced the simulations using detailed tsunami models.

"Tsunamis have struck Washington’s coast many times over our geologic history," said Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz. "It’s a question of when, not if, the next one will hit ... These videos are designed to give the communities that would be most impacted by tsunamis a visualization of what areas are likely to face the most damage so they can make sure their residents, businesses and institutions are secure and resilient."

The videos show Cascadia tsunami wave simulations for the southwest Washington coast, with detailed, localized impacts shown for Grays Harbor and the Long Beach Peninsula, areas where damage from the tsunami in 1700 can still be seen.

For example, the simulations show what would happen to the Long Beach Peninsula. Less than 20 minutes after the earthquake started, the first wave would hit Long Beach. Minutes later, almost the entire peninsula would be under water. And the waves would keep coming.

"The first wave reaches the outer coast in about 15-20 minutes depending on where you are and it quickly travels inland over land through the bays up the Columbia River," said Corina Allen, chief hazards geologist with DNR.

Allen said the waves would move up the Columbia River, but nothing more than a strong current would make it all the way to Portland.

The DNR said these simulations are designed to give emergency planners and communities the best possible visualized information about tsunami impacts and timing so they can plan accordingly.

You can read more about these tsunami simulations and learn about how and where tsunamis occur on the DNR's website.