PORTLAND, Ore. — Back in the mid-1800s, rich men were buying acres of land in downtown Portland, and many of the buyers' names now adorn street signs or parks throughout the city; names like Pettygrove, Lovejoy, Stark, Lownsdale and Chapman.

Pettygrove and Lovejoy were instrumental in helping name the city, and Stark was a businessman and politician. But what about the namesakes for Lownsdale Square and Chapman Square, which are part of a three-block string of park space in the middle of Portland's downtown government hub?

"Daniel Lownsdale and William Chapman, both very influential, powerful people here in the early days of Portland," said Kerry Tymchuk, executive director of the Oregon Historical Society.

Daniel Lownsdale was a politician, businessman and real estate investor. William Chapman was co-founder of The Oregonian newspaper. He was also Lownsdale's attorney and real estate partner.

Both Chapman and Lownsdale owned big swaths of property in what is now downtown Portland. In 1870, Chapman sold two blocks of land, known as block 53 and 54, to the city for $6,250.

In 1892, the two blocks would be named Lownsdale Square and Chapman Square.

"The original intent was for public parks, for beauty, for relaxation," Tymchuk said. "Then a scandal happened."

Before the turn of the century, the beautiful new parks had a problem.

"Men were hanging around these parks and they would talk to, whistle at, yell at young ladies going through the park," Tymchuk said.

This constant problem grabbed the mayor's and city council's attention, and prompted a change to be made. The city would make it against to law to aggressively flirt, whistle at or talk to women that didn't want the attention.

"A regulation that banned men from talking to women 14 years of age and over," Tymchuk said.

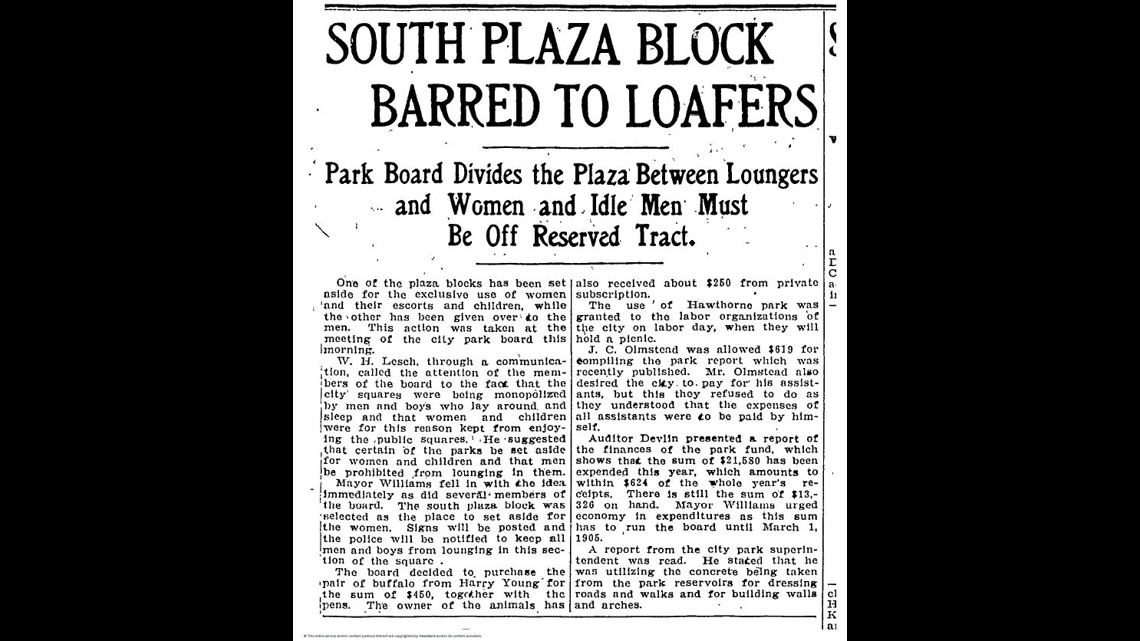

Tymchuk read from an 1894 Oregonian article that said, "The crowd of idle loafers, who for weeks past, have taken possession of the plaza blocks lounging about and sleeping on the grass will be compelled to move on."

Ten years later, it was still a problem. The city opted for a more drastic change, making Lownsdale only for men and Chapman only for women and children, unless they were escorted by a man.

So who were these loafers that were causing such a problem?

"A lot of people who were out of work looking for jobs. Folks who just had nothing to do and loll as they said in the park," Tymchuk said.

The city parks division put the new rules in place, with the possibility of fines or jail time for violators.

"It was called mashing, was the name they used back then," Tymchuk said.

The fine was set at $50 when the city enacted the rules through a 1924 ordinance. The restrictions would stand for decades, although they became less and less enforced as the years went on. But the signs remained at the park, reminding parkgoers about the rules for Chapman and Lownsdale until the 1970s.

The ordinance was formally repealed in 1990, but one relic of the policy remained visible to park visitors until quite recently: each park has a small restroom building, and until at least 2019, the Lownsdale one was designated as a men's restroom and the Chapman one was designated as a women's restroom. Both restrooms were updated to be gender-neutral at some point in the past few years, according to Google Maps Street View records.