CORVALLIS, Ore. — There aren’t a lot of people who get excited to see cockroaches. George Poinar is one of them.

The renowned entomologist and Oregon State University professor has spent his professional career finding new and novel plants and insects encased in fossilized tree resin.

He discovered a new genus of legume frozen in amber, as well a parasitic wasp fossilized next to a flower that no one had ever seen before. He helped unearth the first example of a pinecone preserved just as it was sprouting.

Now, he’s found a new species of cockroach, fossilized 20 to 30 million years ago.

“Cockroaches aren't that common in amber and so this was beautifully preserved. We wanted to study it and describe it,” he said.

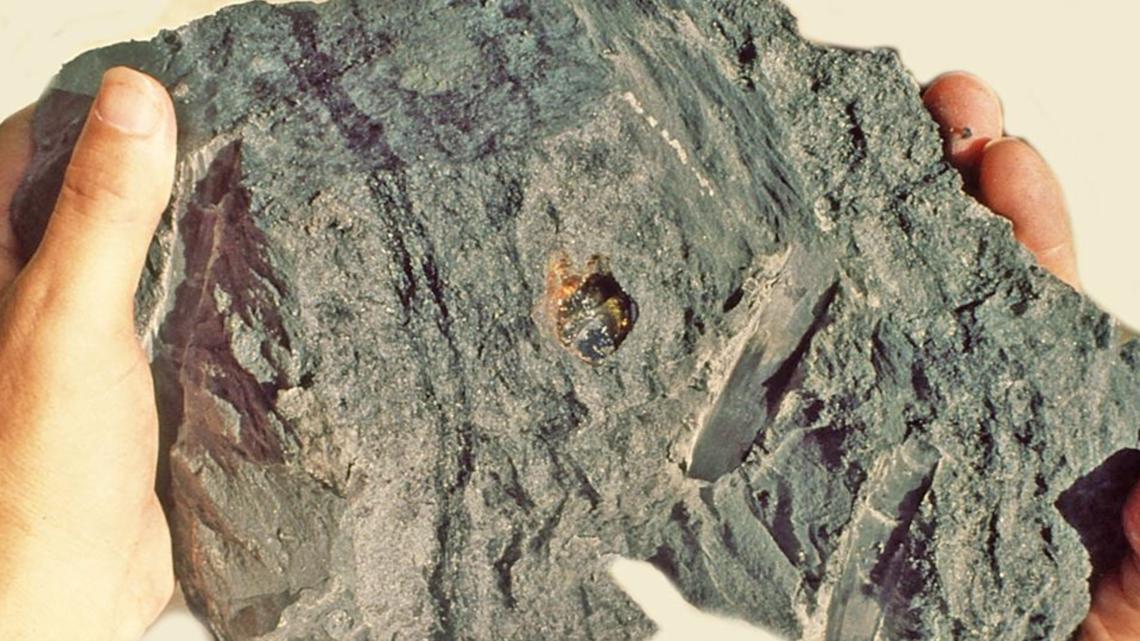

This particular specimen had been waiting to be discovered in Poinar’s lab for decades. He retrieved it on an expedition to an amber mine in the Dominican Republic in the 1980s and just got around to processing it this year.

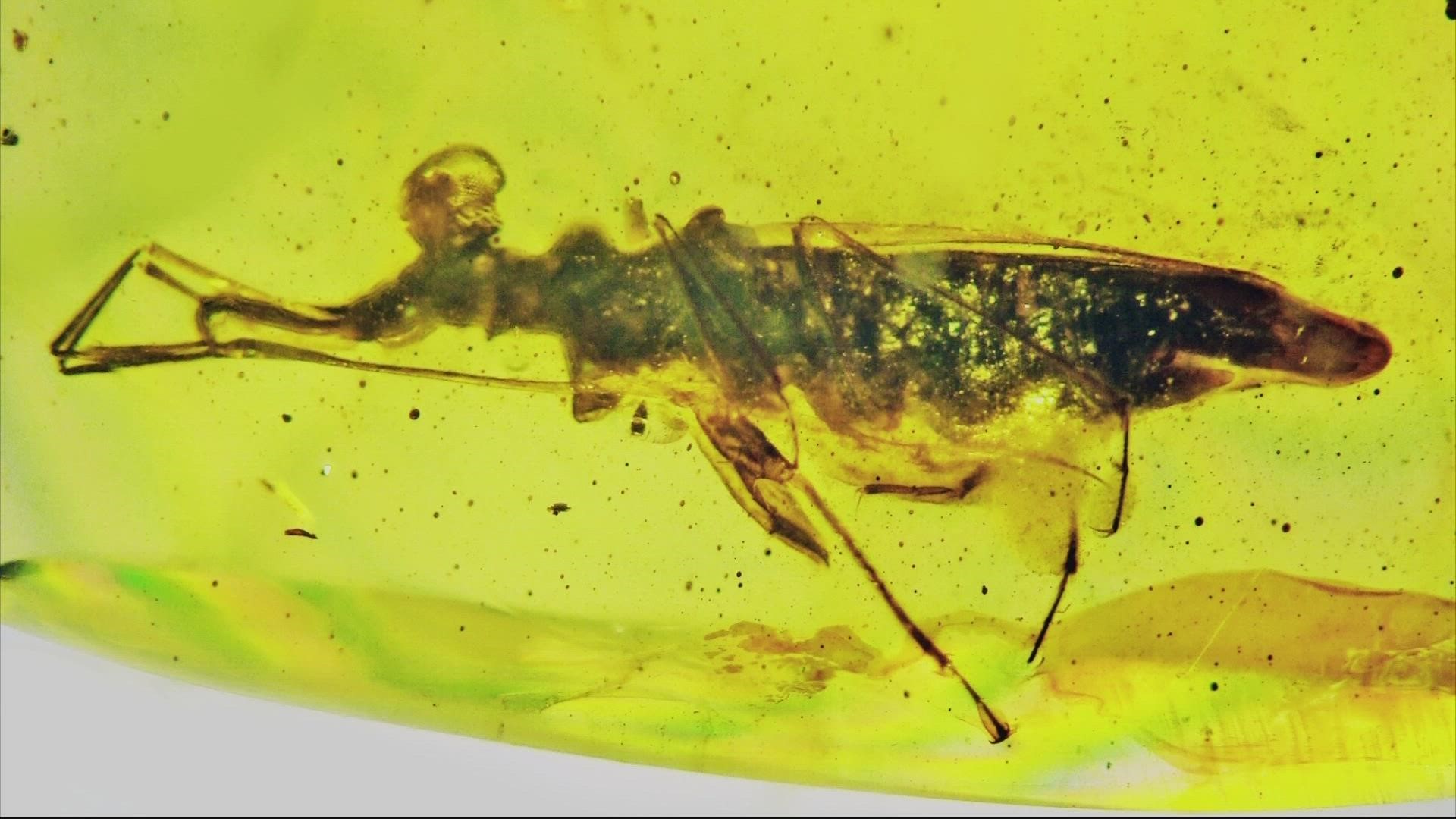

After trimming the amber on a small table saw, sanding it down and polishing it to a gleam, Poinar thought he might be looking at a new species. To be sure, he enlisted a Slovakian roach expert who confirmed that what would come to be named Supella dominica was indeed a new species.

“The coloration of it, the yellow band that went through the center, which seemed to divide the cockroach in two parts,” Poinar said, noting what sets this roach apart from some of its modern counterparts. “Then there was another cross band on it too, which was fairly unique in some of the cockroaches.”

This particular roach no longer has any descendants in the Dominican Republic, Poinar said, with its closest relatives now living in Africa and Asia. It was unclear exactly what killed off Supella dominicana, but Poinar said he thought it could have been a change in the tropical climate many millions of years ago.

The specimen also contained another surprise for Poinar, the male roach had an intact sperm pouch attached to one of its legs.

“In this case, I think the male felt this might be the last thing he was doing,” he said. “We haven't been able to find any other record of it and so that's what made it interesting. You could actually see the little sperm caps on top of the sperm.”

Cockroaches aren’t exactly popular creatures, Poinar conceded. They are amazingly resilient and hard to kill. They can withstand vast amounts of pressure so crushing them is difficult. Some have been known to live for days after being decapitated and they can withstand temperatures well below freezing.

They’re fast, at maximum scurry, roaches can move with the speed-to-body ratio equivalent to a human running at 200 mph.

They can also spread disease by traipsing through dead or decaying matter and then walking across food or countertops.

That’s why Poinar prefers his roaches encased in resin.

“The best place for a cockroach might be in resin,” he said.