ASTORIA, Ore. —

Jim Holcroft doesn’t have many boring days at the office.

Holcroft is the captain of the Essayons, a 350-foot dredging vessel run by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. And his office, at least at this time of year, is the Columbia River Bar, where the West’s mightiest river collides with the powerful swells of the Pacific Ocean.

“They call it the 'graveyard of the Pacific,'” said Holcroft. “You got the wind, you got the swells, you got the monster ebbs coming out and it just creates a pretty hectic, dynamic environment.”

Holcroft, and the crew that runs the Essayons, are charged with maintaining a clear shipping channel through the Columbia River Bar, where cargo ship captains have to navigate not only the currents and winds, but also the shifting seafloor.

As the Columbia River traverses more than 1,200 miles from its headwaters in the Canadian Rockies to its mouth near Astoria, it gathers tremendous amounts of sediment. That silt and sand is deposited just outside the mouth of the river, making for an ever-changing undersea landscape.

That means the Essayons must keep a minimum depth of at least 43 feet in the main shipping channel.

“At least if they can count on the channel being down to depth, that's one variable they don't have to worry about,” Holcroft said.

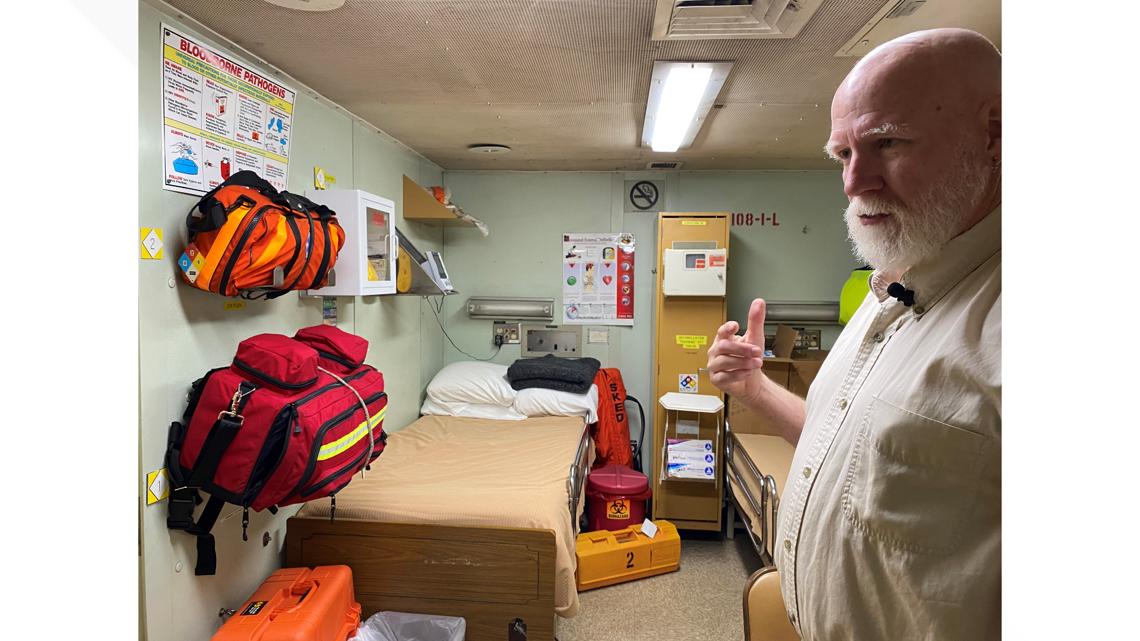

The Essayons is like its own little floating city, complete with a fire department, hospital, gym and full kitchen to keep the 25-person crew fed. They work on alternating 12-hour shifts, from noon to midnight and midnight to noon, running 24 hours a day for two weeks at a time before another crew takes over for the two weeks they have off.

The ship is equipped with two 120-ton suction pipes, called "drag arms," fixed to articulating joints that allow them to drop into the water. Each arm has a powerful pump and a contraption called a drag head that scours the bottom of the sea, able to knock down any high points where sediment has accumulated on the ocean floor.

Once the arms are lowered and the pumps are turned on, the drag heads deliver a slurry of water, sand and silt into the ship’s hopper, a cavernous expanse in the middle of the ship capable of holding up to 6,000 cubic yards of dredged material.

Keeping the navigation channel clear for commerce is important — it's the Essayons’ primary mission, after all — but Holcroft said there’s another aspect of his work that often goes under-appreciated.

“Commerce is big, but so is the environment,” he said. “We've got to be precise about what we take out, but then you also have to be very precisely about where you put it.”

The sand he pulls from the sea floor is valuable, said Holcroft, who has worked on dredging vessels all over the country. It’s clean, especially compared to some of the more contaminated ports on the East Coast, and the sand is coarse, meaning it compacts well.

With a resource like that, you don’t just go dump it in the middle of the ocean.

“The near shore beaches are called 'beneficial use sites' and we try to put everything in beneficial use sites so that it can be reused and kept in the environment,” Holcroft said. “Very rarely do we take everything offshore and get rid of it.”

When the high-value sand is dispersed in beneficial use sites, natural ocean currents wash it up on nearby beaches, replenishing areas that have been depleted by erosion and sea level rise.

“Instead of getting it out there where it's gone and out of sight, out of mind, now we just move it to where it stays in the system and it can go where it's supposed to go,” he said.

While it might seem like Holcroft’s job is to fight against Mother Nature, he’s actually doing his best to work in concert with it.

“Mother Nature disperses it like it's supposed to,” he said. “We're just aiding the migration to the sea. We put it near the beaches, the currents put it back up on the beach.”