PORTLAND, Ore. —

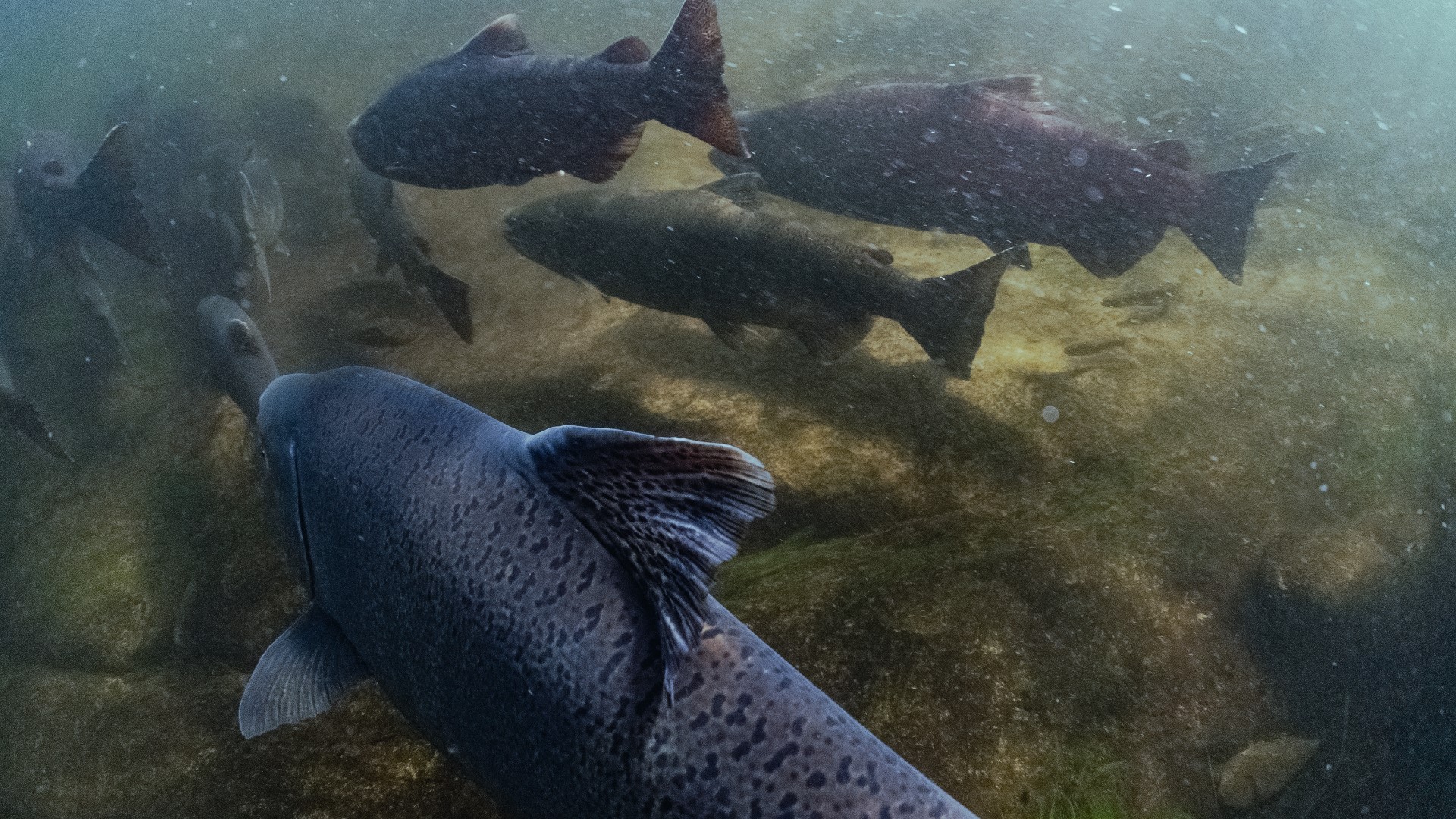

Dangerously low levels of fall run Chinook salmon in two California rivers have forced wildlife officials to shut down fishing off much of the West Coast.

The closure currently runs through May 15 and affects a length of the coast stretching from Oregon’s Cape Falcon, near Cannon Beach, south to the Mexican border. And it could be extended, officials said, as the imperiled species struggles amid a long-running drought.

Further closures are likely, said Eric Schindler, head of the Oregon Department of Wildlife’s Ocean Salmon Program.

“It doesn't look good for this year or next year, and possibly the year after that, because of the drought conditions in California,” Schindler said. “We have to make sure that we're not undermining our ability to produce salmon for the next go around.”

The problem stems back several years when water in California’s Central Valley was diverted from rivers for irrigation, said Glen Spain, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations.

“This was all predictable,” he said, noting that his organization raised concerns about low water levels and poor water quality at the time. “The water that was left for them was way too hot and killed a lot of the eggs.”

The main problems are in the Sacramento and Klamath rivers, Spain said, where Chinook populations have dropped precipitously as the region’s drought has worsened. Salmon live in a 3-year life cycle; hatching in rivers then migrating to the ocean before returning to those same rivers to spawn.

Returning Chinook are expected to be near record lows, according to state officials.

The closure didn't originate with government officials, though. Spain’s organization, and others, petitioned the government to close the fishery to protect the future of salmon in the state.

“We are stewards of the fisheries. If we're going to provide for any fisheries in the future, we cannot be fishing on a stock that is so few in numbers that they're not even going to be able to replace this generation,” he said.

Oregon quickly followed suit, closing ocean fishing for Chinook, both commercial and recreational, through May 15 along the entire coast — with the exception of Clatsop County, where Chinook are more likely to come from the Columbia River.

The economic effects will be felt hard along the coast, according to Steve Fick, owner of Fishhawk Fisheries, a processing company with facilities in Astoria and Alaska.

“People come to the coast to eat fresh salmon in the restaurants. That's going to be a challenge this year,” Fick said. “You take just one 15-pound Chinook salmon caught off the Oregon coast. That’s about 15 meals at $25 to $30 a meal, so that's $600 to $700.”

Spain said it will be difficult for most salmon fishermen to pivot to fishing for other species. There are only a limited number of permits and the fishing industry is highly regulated.

Instead, he’s hoping that the federal government will step in.

“What we need is a declaration from the Secretary of Commerce, who runs our federally managed fisheries that this is a disaster, a fishery disaster,” Spain said.

That declaration would free up federal money to support fishermen and the infrastructure they rely on so it’s available when the Chinook recover.

Just when they will recover is an open question, though.

Schindler said the Pacific Fisheries Management Council, which oversees fishing on the West Coast, will be considering several alternatives in early April.

But with forecasts showing a gloomy picture, he said it’s not guaranteed that there will be any salmon fishing on most of the West Coast this year or perhaps even next year.

“We're in a little bit of a pickle there as far as being able to look forward with an optimistic view for where we'll be next year,” he said.

It all boils down to poor water management in California several years ago, Spain said, and decisions made in the name of “politics” over science.

“We're managed under not only the laws of the states and the federal management system, but under the laws of biology. They are much stricter,” he said. “You violate those at your peril, and that's what happened.”