TILLAMOOK, Ore. — Twelve years ago, news of a never-seen-before phenomenon in the waters off the Oregon coast sent shock waves through coastal communities.

Scientists took note, as did state legislators.

Juvenile oysters were dying by the billions. It was as if something was eating away at them.

The multi-million dollar Pacific oyster industry was on the brink of collapse.

Now more than a decade later, oyster farmers are still dealing with the problem and scientists are still struggling to better understand it.

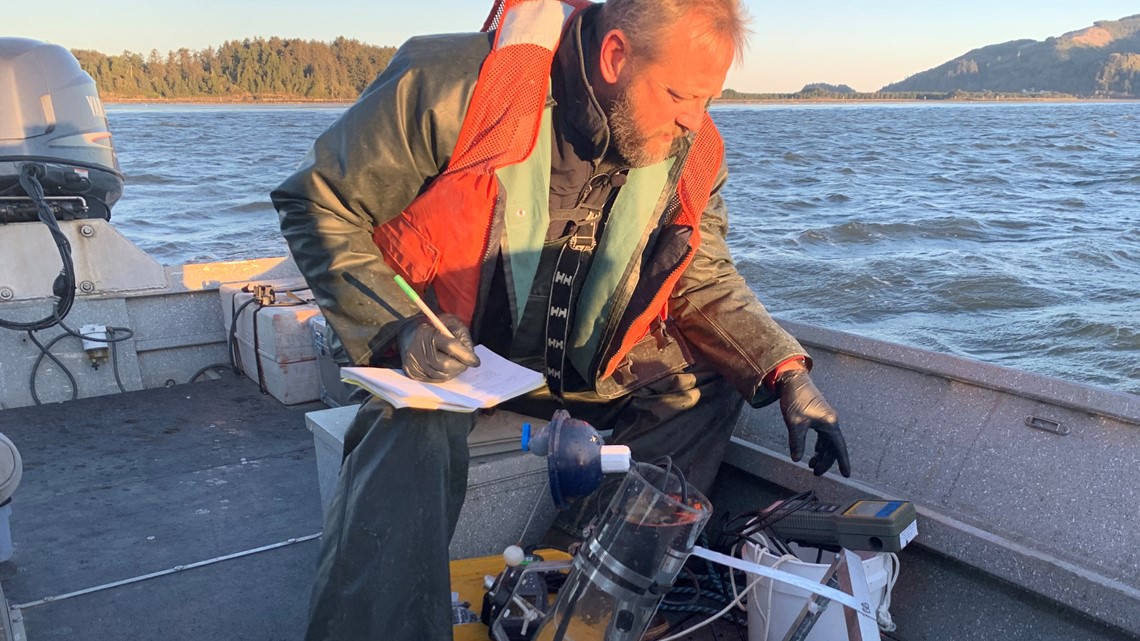

This past fall, researcher York Johnson and biologist Ron Rehn set out on their last research exhibition of the season in Tillamook Bay studying the problem. The scientists invited us to come along.

“We're headed south down the west channel of Tillamook Bay right now to get to our first monitoring location,” Johnson said as we set out.

It was about a 10-minute boat ride from the marina out to the test site. It was late October.

“This was the day I was worried about because it’s getting closer to the fall and winter season,” Johnson said.

But when so much depends on your research, a little sub-freezing wind and near freezing temperatures don't really matter. What these scientists are studying is a big deal.

“It’s really important,” Johnson said .

To truly understand just how important, we'll have to rewind this story about 12 years and head a few miles down the coast to a different bay: Netarts Bay and the Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery – the largest operation of its kind in the Pacific Northwest.

In 2007, the decades-old business experienced something it had never seen before.

It was a time shellfish farmer Mark Wiegardt remembers vividly.

“We came in here one day and we had billions of larvae that died overnight,” he explained. “Nothing in this facility was alive … mass mortality.”

Wiegardt recalled having no idea what was going on. But he did notice something strange.

“The shells weren't forming, they were just damaged from the get-go,” he said. “We thought it was a bacteria. We had no idea what it was.

“Within a week we had people from the governor’s office here, we had Oregon state scientists here.”

Researchers eventually traced the die-off not to any bacteria or disease, but to the water in the bay; the water the hatchery uses to grow the oysters in the tanks is pumped in directly from the bay.

So scientists got to work testing that water and quickly discovered high levels of carbon dioxide.

When carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels, about a third of it gets absorbed by the ocean.

Once dissolved, the CO2 combines with the water and forms something called carbonic acid.

The more the CO2, the more acidic the water.

The water in Netarts Bay had gotten so acidic, the juvenile oysters could not form shells – and died.

“The next thing you know someone says its ocean acidification, we really didn't know what that meant,” Wiegardt said.

But they would soon learn and eventually find a solution.

“The reality became – we can’t fix the ocean, we've got to fix the water coming into the hatchery,” he said.

Now all the water that comes into the hatchery is treated with soda ash which is used as a buffering agent to increase the pH levels of the water so the juvenile oysters can form shells and survive.

“It’s like a morphine drip, it’s taking the pain out of the water,” Wiegardt said.

The hatchery constantly monitors the water coming in from the bay. It even set up a special room just for researchers. Which brings us back to Tillamook Bay and onboard that small research boat.

“This was kind of an eye-opener for Oregon and the West Coast,” Johnson said. “Basically Oregon decided it needed to set up a monitoring network to track changes in ocean conditions. The goal of this effort is to try and establish a cost effective way to monitor ocean acidification over the long term.”

For the last year, Johnson has been tracking just how acidic the water is in the bay.

On the day we went along, he was collecting the final samples of this testing season. All the samples taken would be sent to researchers around the state to help figure out what's really happening with the water in this bay.

They already know the ocean is acidifying. That data is clear. What they are hoping to learn with projects like these is how fast it’s changing and how marine life will adapt.

The problems that started with the oysters are already impacting Oregon’s mussels.

While the adults are able to survive, the young mussels are struggling.

Researchers believe Dungeness crab could be next.

Then there are the salmon. Studies have shown acidic water impairs the ability of fish to find their way home.

Researchers understand that acidic water is reshaping our ocean.

The question now is: What will it look like in ten maybe 20 years?

“I think that is one of the questions we would like to answer,” said Johnson. “But I think the hope is yes there is.”

In the 12 years since this crisis began, Whiskey Creek has become somewhat of a poster child for the problem.

“The Whiskey Creek story about ocean acidification, it never seems to go away, people want to hear about it a lot, of course we live it… sometimes we’d like to have it go away.”

But Wiegardt knows this story will be told for a long time.

It’s story about a vast and beautiful ocean that is sick.

“There's things we can do, each and every one of us to make it better,” he said.

“Someday we'll all get to that point where we don't have much time left in this world and you're going to sit there and you're going to wonder did I do enough.”