BEND, Ore. — The pond is full again at Upingaksraq Spring Alaska Schreiner’s high desert farm. It’s a welcome sight for Schreiner, who owns Sakari Farms north of Bend, Oregon.

Last summer, as drought punished Central Oregon, Schreiner’s irrigation district stopped delivering water. She watched as the pond gradually disappeared, leaving a mud puddle behind.

“I cried last year when I walked through the dry canal,” Schreiner told Oregon Public Broadcasting. “I was pissed. I was like, ‘There’s nothing we can do.’”

Schreiner has rights to a little over two acre-feet of water, which makes its way to the farm from the Deschutes River through a series of pipes and canals.

She only got a fraction of that amount last year.

This year is looking worse.

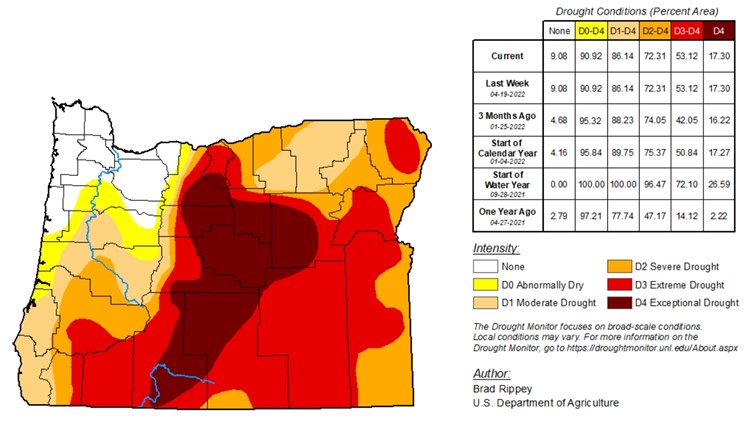

Gov. Kate Brown has already declared drought emergencies in 16 Oregon counties, including Deschutes. That’s the most ever for this time of year, and Oregon farmers like Schreiner are on edge.

“I’m not sure how to cope with going in this year knowing that there’s less water or no water,” Schreiner said.

Schreiner is Inupiaq, a member of the Valdez Native Tribe of Alaska and Chugach Alaska Native Corporation. Her tribal name is Upingaksraq, which means “the time when the ice breaks.” She opened Sakari Botanicals in 2012 and Sakari Farms in 2018 to bolster and restore access to traditional foods for Indigenous people locally in Central Oregon and across the country.

Native people will send seeds to Sakari, which means “sweet.” The farm will grow the plants, collect the new seeds and send them back, keeping Indigenous plant varieties going strong. Sakari also hosts farm education, tribal cooking classes and tribal community events.

Water has sustained that vision to this point, but now Schreiner knows that water is no longer a guarantee.

“All I can do is implement it practically,” she said.

She’s channeling the frustration she felt last year into solutions.

RELATED: Portland General Electric prepares for possible power shutoffs this summer to prevent wildfires

On a hill behind the farmhouse are four old chain-link fence panels surrounding a bare patch of dirt. Beneath the surface is an elaborate pattern of squash seeds, beans and corn — the three sisters.

Schreiner won’t water the plot, but said she’s hoping seedlings will soon emerge from the dirt. She said the moment will surely bring her to tears.

“It’s literally your ancestors telling you thank you for trying this,” Schreiner said.

The hilltop plot represents one of the best hopes for Sakari’s future. Indigenous people, particularly the Hopi, have practiced dryland farming for thousands of years in semi-arid regions, relying solely on rain and snowmelt to grow crops.

“It’s imperative that we look for guidance from Indigenous people on fire management, climate change, water usage, how we grow our crops, when, why,” Schreiner said. “No one asks us how to do things. They just kinda push us in the corner. And that’ll bite them, I think.”

Schreiner is also installing more drip irrigation at Sakari and securing grant money to implement new technologies like weather stations and water sensors on-farm to improve efficiency.

She said she’s learned lessons on what not to do by watching other farmers fail. For example, Schreiner won’t truck in water from elsewhere if her pond goes dry again this year.

“I’m still promoting all the farmers to grow as much food as they can and extend the seasons,” Schreiner said. “But it’s not natural, so that’s where we’re going to be ahead of the game.”

Sakari is almost fully planted and will only plant once this year. Farm workers Harrison Hill and Kobe Stites were busy putting bean starts in the ground on a hot Wednesday in late May.

“The water that we did have to start out the season isn’t always going to be here,” Hill said. “We’re going to have to learn how to use it most effectively.”

Schreiner said if the water’s shut off again, she’ll cut off the farm plot-by-plot and seek financial relief for failed crops.

Still, the plants’ resilience and that of the people who have grown those plants since time immemorial give Schreiner confidence — even in the face of Oregon’s drier future.