LA GRANDE, Ore. —

When Jim Kreider first heard about the proposed transmission line, he was angry.

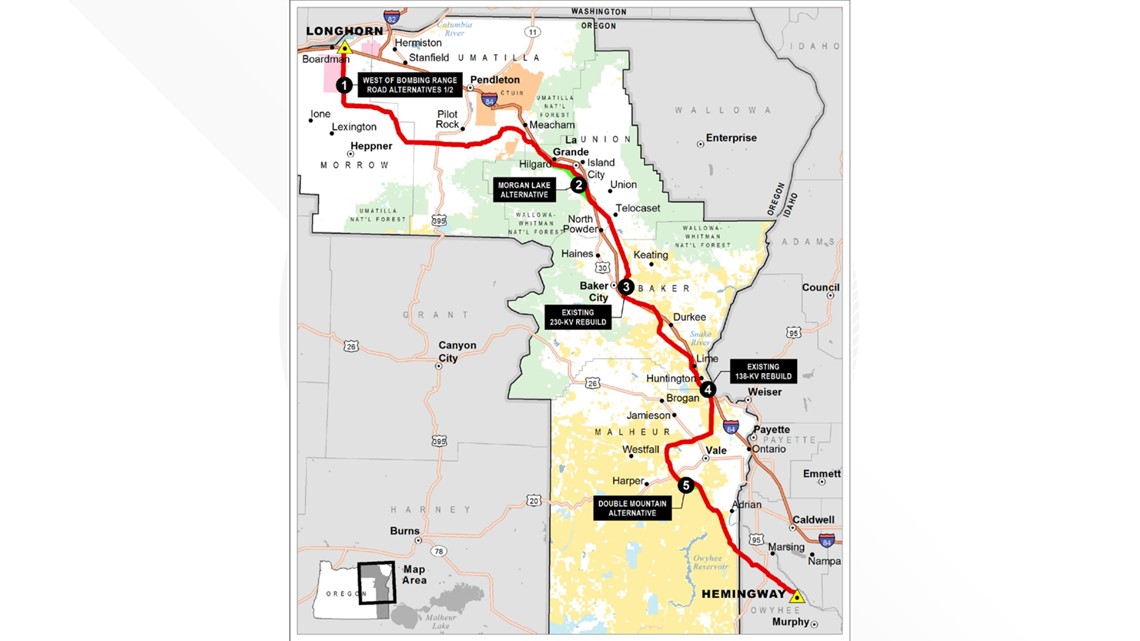

The Boardman-to-Hemingway line, known as B2H, would run 300 miles across five Eastern Oregon counties, including through the hills west of La Grande, where Kreider lives.

At first, Kreider and his neighbors fought with each other about whose property the line would cross.

But after a few tense meetings, they realized there was another option.

“As we came together, we agreed the only thing was to stop the damn thing,” said Kreider, who is co-chair of the STOP B2H Coalition, a grassroots organization that opposes the line.

The B2H line, a collaboration between the Bonneville Power Administration, PacifiCorp and Idaho Power, would transport 500 kilovolts, enough to power 150,000 homes at peak demand, between Boardman, on the Columbia River, and Hemingway, Idaho, southwest of Boise.

Proponents argue the line would be a crucial conduit for green energy and necessary for both utilities and states – Oregon legislation has mandated 100% renewable electricity by 2040 – to meet ambitious climate goals.

“I think a lot of the benefits will lie with the ability to transmit clean energy,” said Ryan Adelman, vice president of power supply with Idaho Power, which has taken the lead in the permitting process. “One of the benefits of the transmission line is that it really is a relatively minimal impact when it comes to, you know, the actual disturbance of the ground relative to what the project is able to do.”

But Kreider and the coalition, which has a mailing list of nearly 1,000 people across Eastern Oregon, say the environmental tradeoffs aren’t worth it for a line that would disrupt views along its entire route, could introduce harmful invasive species and, they say, could be rendered obsolete by changes in the way electricity is produced and distributed in coming years.

“Why would we have a a long-distance obsolete overhead transmission line when they can do smaller micro grids, more decentralized energy,” said Fuji Kreider, treasurer and secretary of the coalition, who noted that rooftop solar panels and battery storage are rapidly becoming more accessible.

“We believe the energy industry is changing so radically and so quickly that it's going to become a moot point,” Kreider said.

An inadequate grid

Oregon isn’t the only state to be pushing for clean power in the near future. Washington has legislation mandating 100% renewable energy by 2045 and Idaho power has set the same goal for itself.

As states and utilities work toward those benchmarks, they’re running up against a problem: even if there is enough wind, solar and hydropower to meet those needs, the grid used to transport that power from where it’s created to consumers, is woefully inadequate.

Emily Moore, director of climate and energy at the Sightline Institute, a sustainability thinktank based in Washington, said that bottleneck could put many of the region’s climate plans in jeopardy.

“The northwest grid is nearing capacity,” she said. “At a regional level, without some more transmission capacity, it's unlikely that Oregon or Washington will meet our clean electricity goals.”

Most of the existing transmission lines in the northwest are owned and operated by the Bonneville Power Administration, which is part of the Department of Energy. Each year, developers and utilities hoping to use the lines must request permission from the administration. Moore’s research shows that, in 2022, 144 such requests were submitted, more than double the amount submitted in 2020.

Of those 144, the administration was only able to guarantee transmission rights to 11 of the requesters, with another 96 getting conditional approval.

“Most of those can't [be] accommodated on the current grid, so they're ending up on long waitlists,” Moore said, noting that many of the projects left in limbo are large wind and solar energy projects aimed at filling the demand for clean energy.

There were more than 600 requests on that waitlist as of September 2022, according to Moore’s research, some dating back as far as 2010, representing 44 gigawatts of power, almost as much as the combined generating capacity of all the power plants, including hydropower and gas power plants, in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana combined.

But building new transmission lines, especially over long distances, is no easy feat. In fact, there’s only one such line anywhere close to construction anywhere in the Pacific Northwest: the B2H project.

A saga 16 years in the making

The B2H line was first proposed in 2007 and has been working its way through the various state and federal permitting agencies including the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service and the Oregon Department of Energy.

When and if it’s completed, the line would be able to send wind power from as far away as Wyoming to the Pacific Northwest in the winter when it’s needed for heating. The line would be bi-directional, also able to send wind, solar and hydropower in from Oregon to Idaho in the summer, when demand spikes in the region because of irrigation and cooling.

“It's necessary for the long-term supply of clean energy to Idaho, and it's the least cost resource for our customers,” said Adelman, of Idaho Power, adding that the utility is expecting to add roughly 250,000 customers in its service area over the next 20 years. “We continue to see year-over-year growth when it comes to sales. We continue to see significant growth in residential customers coming into the Treasure Valley.”

Over the last 16 years, the route has been mapped and changed and mapped again, with community meetings and multiple environmental impact studies conducted throughout the process.

Joe Stippel, principal project manager for Idaho Power, said all relevant agencies have signed off on the plan at every step of the way.

“Both the federal government and the state have thoroughly reviewed our work and concluded that there are no unreasonable impacts,” he said.

Jim Kreider and the rest of the folks with the B2H Coalition have a decidedly different view of the project.

‘An absolute disaster for the ecosystem’

As a young person, Joel Rice saw many of the natural areas he loved destroyed by development and he’s worked ever since to preserve what he can in and around his home near La Grande.

“Before I graduated from high school, I decided I wanted to preserve 2,000 acres at least of land that would stay as a natural habitat,” said Rice, who works as a psychiatrist and addiction treatment specialist. “The idea was to block development and protect that land in perpetuity and the local community could hike and recreate.”

He now owns nearly 2,000 acres, most of which has been set aside for protection by conservation groups, in an area just west of La Grande known as Glass Hill. The proposed route of the B2H land would cut directly through his property.

“My life’s work would basically be destroyed and it’s hard to talk about without wanting to cry,” he said. “The power line would just be an absolute disaster for the ecosystem.”

Along the entirety of the 300-mile route, there would be more than 1,000 steel towers, each standing between 100 and 200 feet tall. Construction plans also call for 200 miles of new access roads and another 222 miles of improvements to existing roads along with 10 new communications buildings.

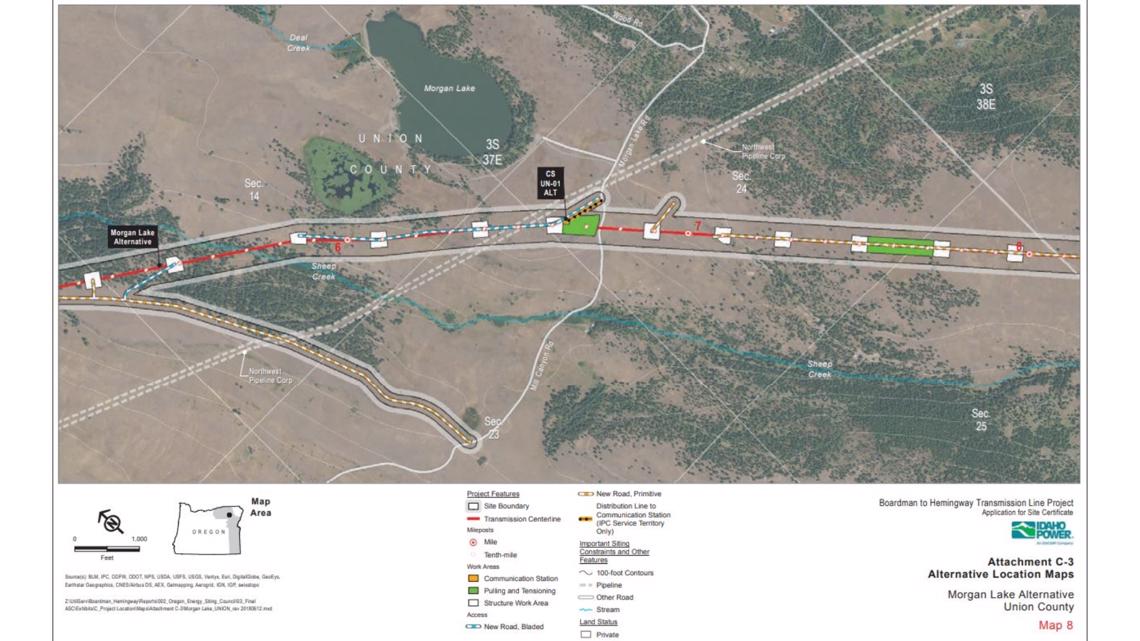

In Union county, the route would take the line just west of La Grande tucked behind a hill and out of sight from the city itself, but it would be right along the edge of Morgan Lake Park, which locals cherish as one of the few dedicated recreation areas just outside of town.

“If you've ever been up here on a Saturday afternoon in the summer when the fish are biting...the community loves this place,” Karen Antell told KGW while standing in the snow at the park in February. “The community loves this park. The community loves having access to wild places.”

The hilltop park is home to two spring-fed lakes along the ridge top as well as a number of rare plants and vulnerable animal species, said Antell, a retired botany professor, former manager of a nearby research forest and member of the STOP B2H Coalition.

“It's just a unique place along this whole ridge top,” Antell said. “There’s really interesting botanical diversity and interesting aquatic plants, but also it’s an important stopover location for migratory birds, because of the mature Ponderosa pine forest that's here as well, it's a prime habitat for a wide diversity of avian species.”

One of Antell’s primary concerns is the potential that all the new and improved roads could introduce invasive species. Construction plans for the line include stipulations that crews watch for vulnerable or endangered species and create buffers when they’re found, but Antell isn’t convinced that will provide any meaningful protection.

“The thing about rare species is they're rare for reasons,” Antell said. “It’s virtually impossible to transplant these kinds of rare species into other places and expect them to thrive and survive.”

But the reasons the coalition has for opposing the line are almost as varied as its members -- which include conservatives, liberals, environmentalists, hunters, farmers and activists.

In Morrow County, members worry about wildfire risk. In Umatilla County, sheep ranchers are concerned about how the line will impact their livelihoods. In Baker County, the route would take the line directly in front of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center, across one of the more scenic views in the area. And, in Malheur County, the line would go directly across the mouth of the Owyhee Canyon before it crosses into Idaho.

“The process was designed to come up with the best, least environmentally damaging," Antell said. “And then we ended up with probably the most environmentally damaging route that they could have chosen.”

The STOP B2H Coalition has opposed the line in every venue available, through federal and state regulatory agencies, over the last several years, but Jim Kreider stressed that the group does not oppose renewable energy.

“We all understand we need to electrify the country, but we need to do it the right way,” he said.

The coalition’s last stand

Having exhausted all their other options, the coalition argued their case in front of the Oregon Supreme Court in December, taking issue with the Oregon Department of Energy’s approval of the route despite it seeming to conflict with rules about noise pollution and other issues.

Fuji Kreider said she isn’t under any false pretenses that a small group of motivated residents will actually stop the $1.3 billion project, but she hopes that with enough delays, the utilities will recognize the coalition’s argument about decentralized energy production.

“It's not a strategy just to delay like we think they will stop or drop the ball,” she said. “The longer I think that we give them the opportunity to do the right thing, they more likely they will do the right thing.”

Fuji Kreider was proven right on Thursday when the Supreme Court ruled against the coalition, allowing the project to move forward.

Moore, the energy expert from the Sightline Institute, said there is indeed a tremendous amount of untapped potential for rooftop solar and battery storage to fill some of the energy needs of the Pacific Northwest without the need for long-distance transmission lines.

“About a third of Oregon's electricity demand could be met by rooftop solar, and we're nowhere near that, so there's a lot of room for growth there,” Moore said. “And I think we absolutely should be doing everything that we can to scale those up to their maximum capacity and doing so will reduce the amount of new transmission that we need.”

But even with advances in energy production and storage, Moore said it was unlikely that small-scale solar and battery storage will be able to meet the power needs of the Pacific Northwest, especially as more people switch to electric vehicles and swap gas-powered home appliances for electric.

So that leaves much of the region at an impasse, Moore said, with new sources of renewable energy coming online, but no way to get the power they produce to the people that need it.

And blame for that falls not on the people who oppose projects like B2H, but on the failure of politicians and utilities who haven’t adequately planned for the coming transition.

“One of the big challenges that I've seen through my research is that there's actually no regional or state level transmission plan in the northwest,” Moore said. “We need to develop a 20-year plan to identify exactly how much more transmission we need and to be able to start siting it in a thoughtful, responsible way and minimize unnecessary build out and harm to potentially sensitive ecosystems.”

As for B2H, with the Supreme Court's ruling on Thursday, Idaho Power plans to move forward and the line should be fully operational by 2026.

But Fuji Kreider is still holding onto hope that changes in the energy industry will force the utility to reconsider before the first towers go up.

“I'm not so grandiose to think we're going to stop the line,” she said. “But the energy industry will stop this line and we believe in that. We believe in the changes that are coming.”