PORTLAND, Ore. — Amid back-to-back weeks of heavy rain in April, it seemed a bit incongruous to see Gov. Tina Kotek's office issuing local drought declarations for some Oregon counties.

It's never been a good idea to use Portland's weather as a yardstick for conditions in the rest of Oregon, but the wetter weather this winter and spring hasn't been limited to the northwest corner of the state. The state's snowpack has made big gains, more than it saw last year.

This isn't the first time Oregonians have emerged in the spring only to find that drought conditions are still very much present in the state, but the intensity of the past few months seems like enough to raise the question again.

THE QUESTION

Has Oregon had a wet enough winter and spring to pull itself out of drought?

THE SOURCES

- Larry O'Neill, Oregon State Climatologist

- Ryan Andrews, Hydrologist, Oregon Water Resources Department

- U.S. Drought Monitor

THE ANSWER

No, this past winter and current spring hasn't been enough to end Oregon's drought. Recent cool and wet weather has led to improved conditions in much of the state, but parts of eastern Oregon can still expect to face water supply problems this summer. It will likely take several years with favorable weather to truly end the drought.

WHAT WE FOUND

Individual rounds of heavy rain can certainly help ease drought conditions, according to state climatologist Larry O'Neill, especially in areas with mild or recent drought. But the drier parts of Oregon are enduring a multi-year water deficit that's become too big to be fully cancelled out by one wet episode.

"The drought did not come about because of a lack of a single storm, and so it won't take a single storm to completely recover from the drought conditions," he said. "There are large parts of central Oregon where since 2019 it's missed out on a complete year's worth of rain there."

Oregon also has a pretty stark geographic divide when it comes to drought conditions, and wet weather benefits tend to be similarly uneven. Above-average rainfall has left much of western Oregon in pretty good shape for the summer, O'Neill said, but the same can't be said east of the Cascades.

"Out near Crook County is kind of the epicenter of the drought the last few years, and then Deschutes County and down into the Klamath... and this year we did not receive enough rain, not even a normal amount of rain that we usually get during our wet season in that region," he said.

Some of the winter benefits have been shared statewide — most notably snowpack levels, which are in great shape everywhere — but other drought indicators like soil moisture remain in trouble in central and eastern Oregon.

"When we have a good snowpack, the first place that that's going to go when it starts to melt out is it's going to replenish the soil moisture," said Ryan Andrews, a hydrologist with the Oregon Department of Water Resources. "So what that does is it reduces the amount that's available to translate into runoff and stream flow to help water users meet their demands."

Drought conditions also exacerbate wildfire risks, and O'Neill noted that the latest data from the Northwest Interagency Coordination Center shows the drier parts of central and eastern Oregon also face the highest fire risk this summer.

Counterintuitively, a wet winter can exacerbate wildfire risks in drought-prone areas, he added, because it allows small undergrowth to bounce back, only to become fresh kindling later in the summer.

"As long as the ground stays wet and everything, that will help reduce wildfire risk, but at the same time it actually grows a lot more fuel, and so when it dries out... it is a little bit of a paradox," he said.

The good news

All that being said, the past winter has definitely made a dent in the drought. In fact, this year is a good example of what it takes to get out of drought, Andrews said — it's just that it's too big a problem to be solved by a single good year.

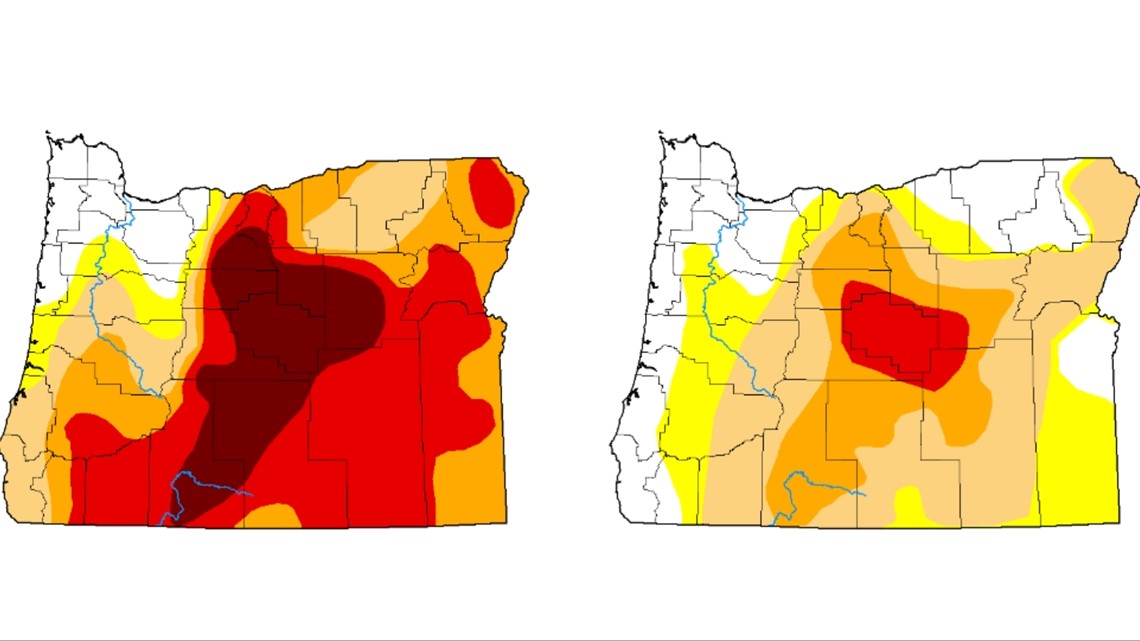

The U.S. Drought Monitor map shows a clear improvement in much of Oregon compared to conditions at this time last year. Most parts of the state that were experiencing drought in late April 2022 are still in drought today, but the severity has lessened nearly everywhere.

A large swath of central Oregon was previously experiencing Exceptional Drought — the most severe classification — but none of the state is in that category today. And a few pockets, including the southern Oregon coast, have dropped off the drought scale altogether.

Oregon started the current water year — which begins in October — in a precipitation deficit, Andrews said, but a series of atmospheric river events began arriving in January, and there have been notable improvements since then.

Precipitation is important, but persistent low temperatures this year have also played a critical role in improving conditions for Oregon, Andrews said, because they've allowed the state to build up its large snowpack and then sustain it farther into the year.

A drawn-out, gradual snow melt helps streams stay fed into the summer, and it reduces the demand for water for human uses.

And the gains haven't just been limited to western or northwest Oregon. Parts of eastern and south central Oregon have seen good precipitation at high elevations this year, Andrews said, and crucially, they've also seen cooler-than-average temperatures.

"All basins, so basically all places throughout the state, have seen well above their typical snowpack, the peak of snowpack," Andrews said. "In previous years, we've seen that we haven't reached the typical peak, but we've also melted out much earlier than we would like to see and much earlier than usual."

Long-term outlook

The current drought is occurring against a backdrop of accelerating climate change, raising questions about whether the current conditions might represent a new normal for Oregon. But it's hard to draw an exact causal line.

Oregon has historically gone through wet and dry periods, O'Neill said, and the current drought is one the longest dry periods on record, but the low precipitation is still largely a matter of natural variability, so it's quite possible that things could swing back.

"What we see in the climate models simulations is that we're not actually projecting a decrease in precipitation in Oregon due to climate change," he said. "So we're expecting about the same amount."

There are examples of drought recovery and drought-free periods in the state, Andrews said, and you don't have to look too far back to find them.

"There have been years in the past, and just in the past 10 years or so, where we haven't received any drought requests... and so I think there's certainly points where the state has been drought-free," he said.

Here's the catch: the impact of climate change is mainly felt through higher temperatures, which means it can lead to increased evaporation that dries out the soil, requiring progressively more water to replenish it, O'Neill said.

"What we're expecting is, because of the gradually increasing temperatures, we're going to get more evaporation in the summers," he said. "And so essentially what that means is the same amount of precipitation will not go as far to meet our water supply needs in the future as they did in the past."