VANCOUVER, Wash. — Archaeology students from Portland State University, Washington State University Vancouver and a handful of other universities are learning hands-on by digging through small sections of Vancouver's waterfront.

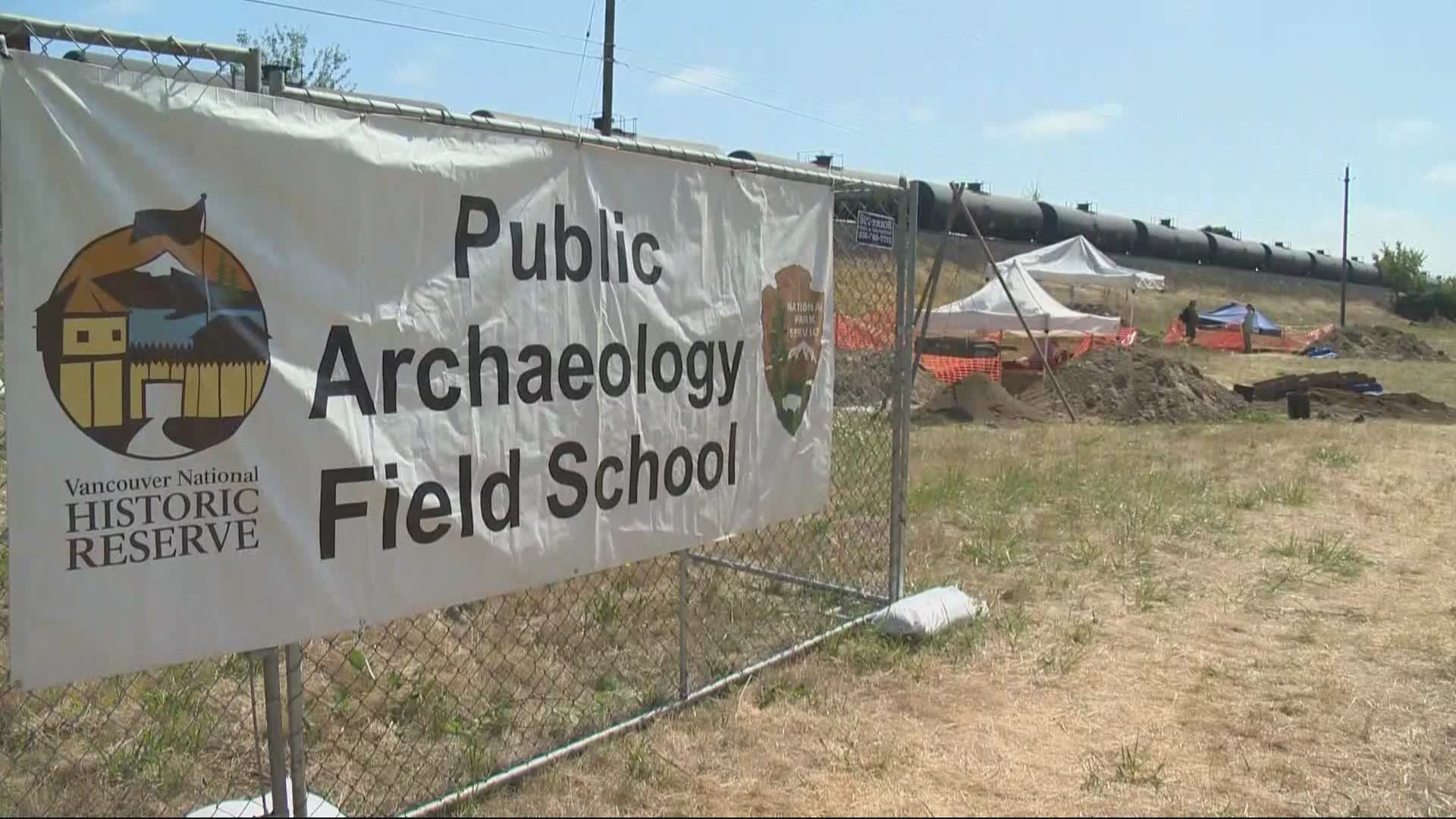

The students are participating in a six-week class as part of Fort Vancouver's 2021 Public Archaeology Field School.

"It's an area that we have not intensively studied," said Doug Wilson, an archaeologist with the National Park Service. "This place is particularly special. It's a place where they had a whole complex of buildings. There were the docks, there was a boatworks, there was a hospital. That hospital was associated with the epidemic of malaria that hit this area in the 1830s."

Wilson said they'd like to learn more about what happened and how people lived during that time period.

"We can look at more of the common people and their daily practices and learn more about the incredible diversity of people that made up the fur trade community here at Fort Vancouver," said Wilson.

At least four sites along Columbia Boulevard in Vancouver are being excavated during the school's course. While most people use history books or documents to learn, students in this course use shovels, spades and buckets with hopes of unearthing a piece of history.

"By studying their tangible belongings, we can learn more about who they were as a people, and sometimes it contradicts what the historical record says," said Wilson.

At one site, students like Sarah Storm were searching for remnants of an old pond site. Storm pointed out evidence of burned ground about 4 feet beneath the surface.

"We're finding throughout this level, there's been kind of charcoal and burned dirt. And this rock here on the edge is black on this edge, so you can tell it's been cracked by a fire. There's a charcoal piece over here," Storm said while pointing out rocks and burnt spots on the ground.

When the railroad was built in the early 1900s, 3 to 4 feet of dirt was brought in to build up the ground, which adds an extra layer of work when trying to find the edges of an old hospital.

"From our standpoint, we want to find that location because of its ties to this time of tremendous change to the colonial period." Wilson said. "Back then, the malaria epidemic, it swept through the indigenous people of the lower Columbia. 90% mortality, so just an incredibly devastating disease that hit the people here at Fort Vancouver. It hit the fur traders, but many of them recovered because they had medicines. Most of the indigenous people, many of them were almost wiped out."

Cassandra Spillane from The State University of New York (SUNY) came out to the Fort Vancouver site specifically for this course. She was digging at the hospital site, removing excess fill dirt.

"Out here with the fort, there's really interesting history with continued occupation that not a lot of places have," Spillane said. "You have Native American sites, then you have colonial history, then you have Army history up until modern, and you don't get that a lot."

Over the course of the field school, students will learn archaeological field techniques, identify and process artifacts and learn how to properly document their findings.

"It's an interesting feeling pulling stuff up out of the ground and wondering you know like, that belonged to somebody," Storm said. "The things that you pull up — what happened the last time that somebody touched this? Why did it get thrown away? The personal stories are kind of what attracts me to the archaeology and getting to tell those stories."

The public is invited to watch the students dig, interact and ask questions. The field school runs from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. until July 30.