MAX attack, one year later: 'It’s a wakeup call, but a wakeup call to what?’

One year after the most violent crime in TriMet history, Portland honors the victims with a vibrant mural and outpouring of support. But Portland's long-term response to the tragic attack is just starting to take shape.

PORTLAND, Ore. – On May 26, 2017, the most violent crime in TriMet’s history left Portland in shock when an attacker, spewing hate speech at two young women on a MAX train, allegedly stabbed three men who stepped in to intervene.

Two of the men died and a third was left with a gash from chest to chin. They would later be hailed as heroes as the city mourned the loss of life and grappled with the meaning of a horrific hate crime on Portland’s public transit system, which thousands of people ride every day.

One year later, the suspect is in jail awaiting trial and a vibrant mural honors the victims of the attack. The mural will be dedicated on Saturday, on the anniversary of the stabbing.

But the elusive question remains for a progressive city with a history of intolerance: How will Portland change after the attack on a MAX train?

Victims showered with donations; attacker awaits trial

On a Friday afternoon last year before Memorial Day weekend, 35-year-old Jeremy Christian was riding on a MAX train when witnesses say he yelled racial and religious epithets at two young black women on the train, one of whom was Muslim and wearing a hijab.

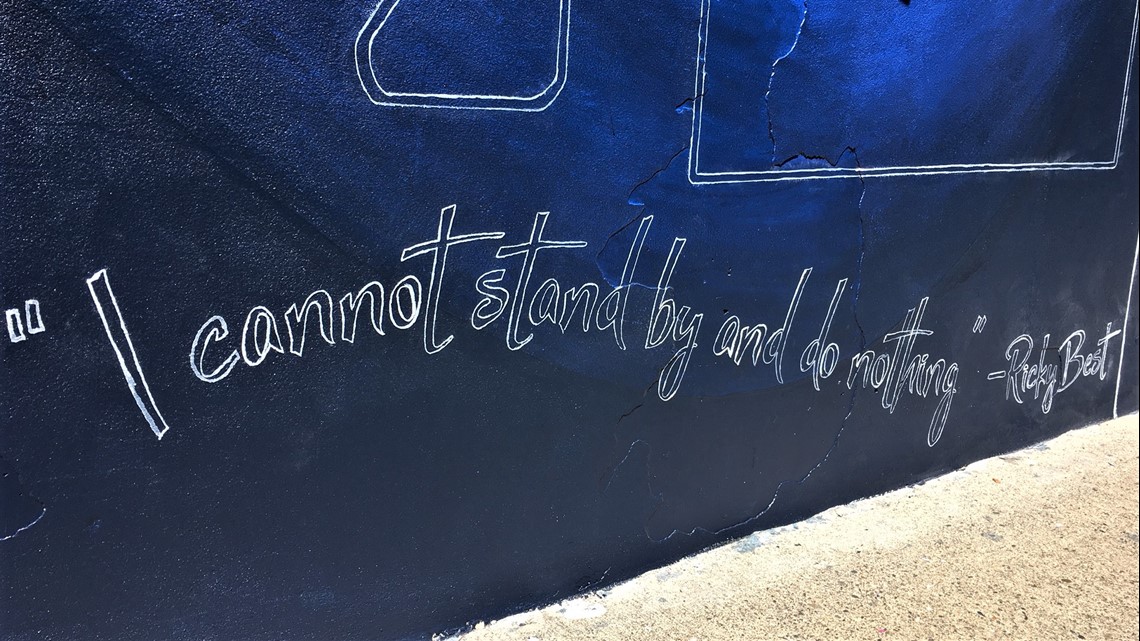

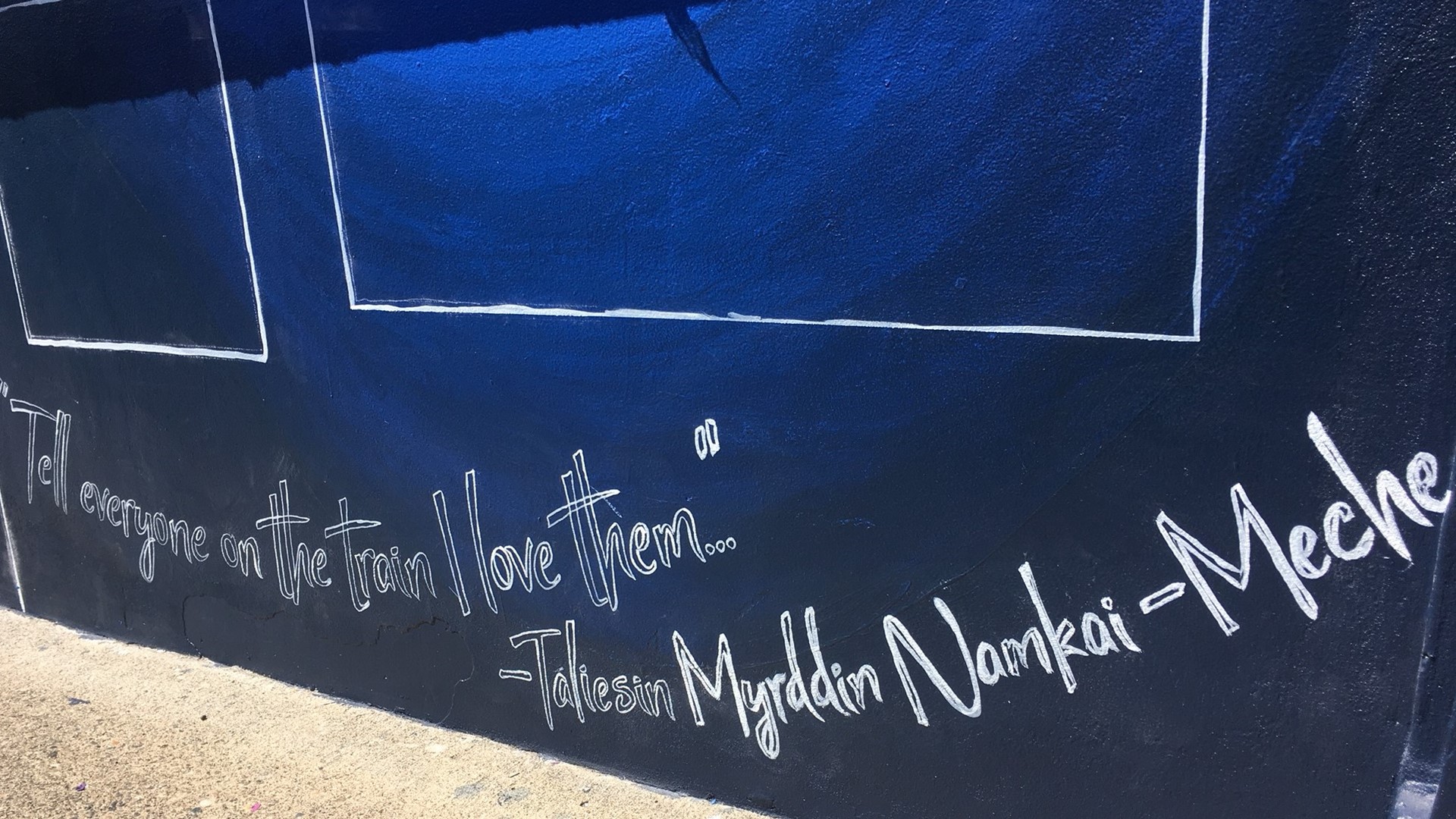

When the train stopped at the Hollywood Transit Center in Northeast Portland, three men stepped in to try and calm Christian down. Christian allegedly slashed the throats of all three men. Army veteran and city employee Ricky John Best, 53, and recent Reed College graduate Taliesin Myrddin Namkai-Meche, 23, were killed. Portland State University student Micah Fletcher, 21, was wounded but survived.

Christian confessed to the killings, police said. His murder trial is set for 2019.

The attack left Portland residents in shock. The apparent randomness, racially fueled violence and sudden deaths of two people who stood up to hate shook the Portland community. A makeshift memorial overflowing with messages to the victims and assurances of love and acceptance blossomed at the Hollywood Transit Center.

Fundraising campaigns also proliferated, with more than $1.5 million raised for the men who were stabbed and the two girls who were berated.

Some of the money has already been distributed to the victims. But two pots of about $600,000 each that were raised for the three men, in a GoFundMe account and a local Muslim group’s fundraiser, were tied up in a legal battle. A lawyer hired by the Best family argued that the family should get more than an equal share, according to an Oregonian report.

A state of Oregon judge is privately distributing the money from the GoFundMe account. A spokesman for the Muslim group, the Muslim Educational Trust, told the Oregonian it distributed the funds equally between Micah Fletcher and the families of Ricky Best and Taliesin Namkai-Meche.

The Best family has publicly remained quiet following the attack.

The family of Namkai-Meche spent the past year honoring his legacy by spreading messages of love. His brothers walked the Camino trail in Spain to spread some of his ashes. His mother, Asha Deliverance, also used ashes to create sacred Buddhist statues called Tsatsas.

Deliverance told KGW she is also working on a book “about this profound event that rippled in hearts across the globe.”

Micah Fletcher has taken a leadership role following the stabbing. Fletcher was elected to a neighborhood association board in October. Fletcher, a poet, also continues to speak about the impact of the attack and the difficulties he faces as he works to recover from that day.

A vibrant tribute

This Saturday, a dedication ceremony will celebrate a new tribute mural at the scene of the attack. The mural, painted in rich hues with text sweeping in waves up the walls of the Hollywood Transit Center, will be commemorated at 4 p.m.

An interfaith service at the Muslim Educational Trust center in Tigard will take place at 6:30 p.m. Fletcher, Deliverance and several others will speak.

The transit center mural honors the victims of the attack, as well as the makeshift memorials left by mourners at the transit center in the days following the stabbing.

The mural was designed by artist Sarah Farahat. It is called “We Choose Love.”

A commemorative plaque is being designed by John Laursen. Work for the plaque was put on hold until after Christian’s trial.

Laursen, who also worked on the Holocaust Memorial in Portland’s Washington Park, said Christian’s impending trial leaves the story unresolved and the historical significance of the attack has not yet been determined.

“The timing turned out to feel too rushed to do a thoughtful, careful remembrance of what happened -- of the loss of life, of the impact on Portland and the community, the community outpouring of grief, and also the love that was demonstrated in all those words that were chalked onto the walls, the candles, the flowers -- there was this tremendous community response that was unifying and heartwarming,” Laursen said. “It will be a goal that will be more easily approached a year or two years from now.”

Has Portland changed?

The attack happened twelve months ago, and pieces of the story remain untied but soon that will change. Christian will go to trial. The donations will be distributed. The victims and their families will find the best way they can to move on. But the individual journeys of those immediately impacted by the attack are not the only ones that will take place. Portland must reckon with the attack and what it signified, and decide what lessons to learn from.

That work is just starting.

“The crime opened up some old wounds that go way back to the founding of this state,” said sociologist Randy Blazak, who served on the TriMet advisory board to pick mural artist Sarah Farahat. “It’s a hard metric to measure. How healed are we later? There’s not really a good barometer to measure that. There’s still hate happening in the city.”

Hate in Portland is part of its past and its current state. Hate crimes increased in 2017 over 2016. The Portland Police Bureau confirmed five bias crimes since the MAX attack, and is reviewing 14 more cases to determine whether or not they are hate crimes.

Crime on TriMet is also higher in 2017, even though ridership is down. There were 714 reported crimes on the MAX last year, 129 more than 2016. Sixty-five of those crimes happened between the Hollywood Transit Center and Northeast 82nd Avenue, nearly double the reported crimes from 2016.

Downtown Portland saw the most crimes on the MAX by location, with 123.

Public safety fears are also rising: A ridership survey found 73 percent of people who ride the MAX feel safe, compared to 78 percent last year. The transit agency said it attributes that sentiment to the MAX attack.

Riders at the Hollywood Transit Center told KGW they usually feel safe, but some have witnessed hate crimes on the MAX since the attack.

One rider named Raphael said a man yelled racial slurs at him after his kids bumped the man on the train. Another rider named Daniel said he saw a man on a MAX train yell racial slurs and punch an Asian man in the face.

For many in a predominantly white city, the MAX attack was a wakeup call to a culture that has always been rippling under the surface.

“The awareness has moved toward the front of people’s consciousness,” Blazak said. “A lot of white people were shocked, but a lot of nonwhite people were not shocked. What that crime allowed us to do is have that conversation.”

The conversation and ones like it prompted by other hate crimes, Blazak said, are important in shaping the attitudes of residents in Portland and beyond.

“We’re much more conscious of the level of trauma people of color and immigrant populations go thorough. It’s a silver lining. It’s not that we’re better about it, but we’re more aware it exists.”

For John Laursen, who will write the plaque commemorating the victims and community response to the MAX attack, those conversations will help determine the lasting impact of what was either a singular event or the start of something more sinister that will unfold over time.

“It’s a wakeup call, but a wakeup call to what exactly? Does something like that make you more likely to stand up or less likely to stand up? We don’t know,” he said. “We don’t know if this was just the really bad thing that happened in Portland, or is this the beginning of really awful stuff. We don’t really know. I’m not sure if we’ll know in a year, either.”