IDAHO, USA — Editor's note: The State of Idaho, through Latah County Prosecuting Attorney William Thompson, on June 26, 2023, filed a notice of intent to seek the death penalty for Bryan Kohberger, the man charged with the murders of four University of Idaho students.

The Ada County Coroner watched Jan Englund’s six-month-old baby in December of 1990 as she ran across the street to break the news to her parents that her younger brother was killed in a brutal beating. Thirty-two years later, Englund's wounds reopen every time she hears news about a murder – and she always thinks of a victim’s family members, who are feeling unimaginable, painful and unbearable grief.

Those same feelings resurfaced when she learned four University of Idaho students were found stabbed to death in their home in Moscow on Nov. 13, 2022. The University of Idaho is Englund’s alma mater, a place she always believed was safe.

The killings in Moscow still leave people wondering how the case against the man charged with students' murders, 28-year-old Bryan Kohberger, will move forward. Speculation about the case has run rampant on Twitter and other social media sites, with users questioning how long it'll take until the public will know what the state will do.

A 60-day clock began ticking on May 22 for Latah County Prosecutor Bill Thompson to file a notice of intent to seek the death penalty against Kohberger.

If Kohberger, a former Washington State University criminology student, is found guilty of the murders and the jury recommends a death sentence, it may be a very, very long road – a road that Englund says will always bring grief, pain and sorrow to the families of the victims.

The man who murdered Englund’s brother was executed for his crimes fairly quickly in comparison to other members on Idaho’s death row. It doesn’t change anything, she said, even though she wanted her brother’s killer to die.

There will never be closure.

Idaho’s only voluntary execution

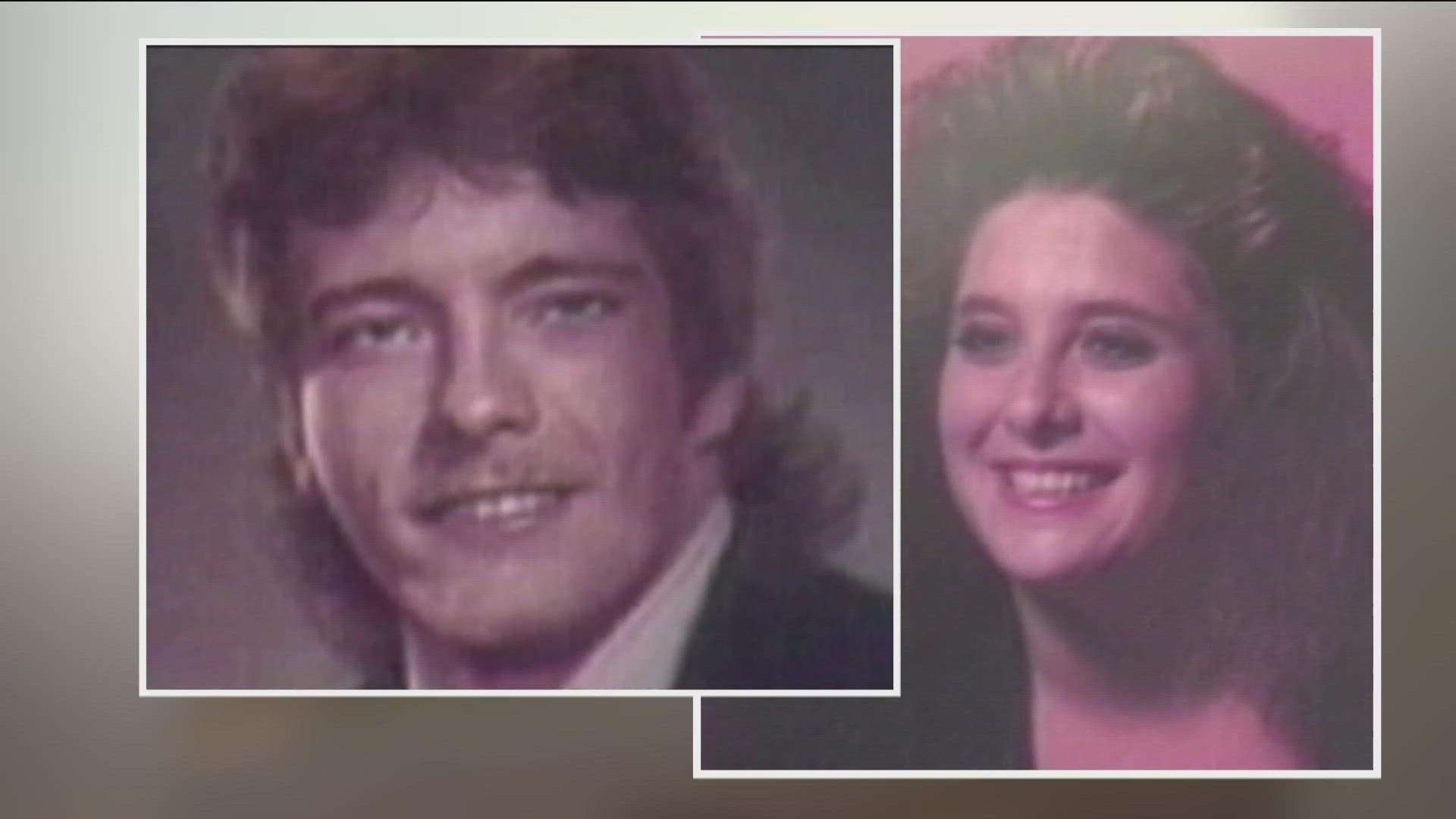

On a below-freezing, blizzarding night at the Rose Pub in Boise on Dec. 20, 1990, Englund’s brother, 23-year-old John Justad, was a customer sitting in the pub waiting for the bartender, Brandi Rains, to close early due to weather. As former Boise Police Det. Dave Smith described it, Justad was “in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

That’s when a 31-year-old man out on parole for robbery walked in the bar and began violently beating Justad over the back of the head, Smith said.

When bartender Brandi Rains came to see what all the commotion was about, she was also brutally murdered. Englund said law enforcement told her a man had walked into the bar, saw the bodies on the floor and ran to a business nearby to call the police.

Smith arrived at the pub, where he observed a chaotic, horrific scene.

“I saw a lot of death scenes working homicides for 20 years,” Smith said via text message. “But not many with that much blood.”

Englund said there were bruises up and down Justad’s hands from trying to defend himself from the blows. He was still alive when police got to him, Englund said, but he was taken to the hospital “just waiting to die.”

At the time, DNA testing was barely in its infancy, and there was little indication as to who murdered Justad and Rains – or why.

“(Justad) was kind of just starting his life out… He was getting ready to move in with a roommate. I just had a baby, he was all excited about that – he came over all the time to see him. It was just such a loss because he was so young, it was so violent. And so abrupt,” Englund said. “You wonder if he would’ve gotten married, how many kids he would have, typical things. He was such a nice, nice young man.”

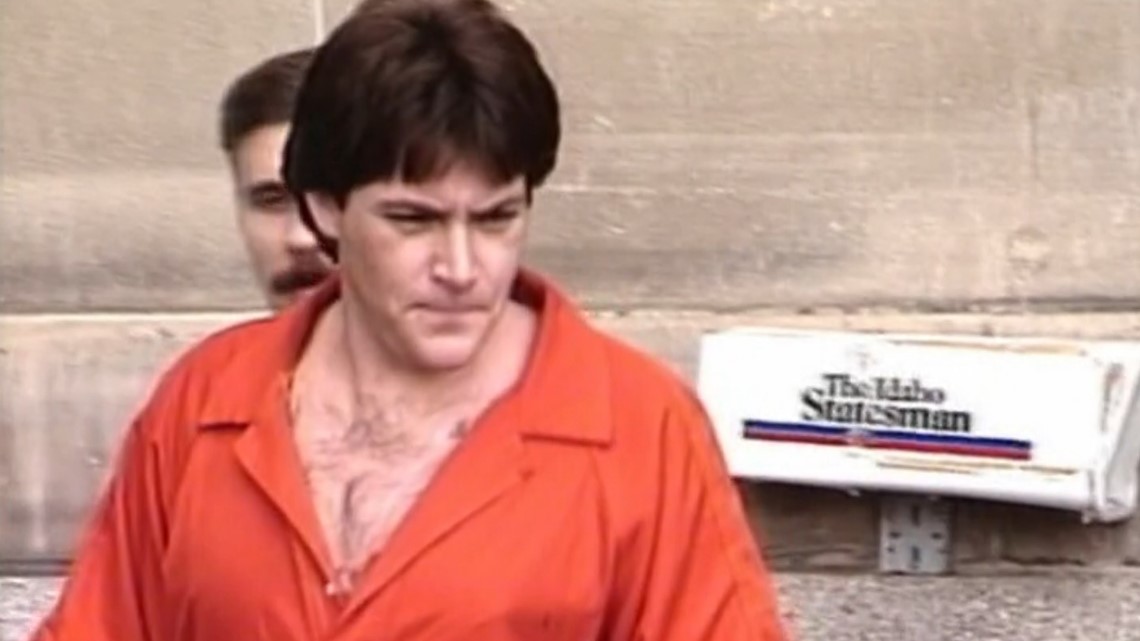

Thirty-one-year-old Keith Wells, who was on parole for robbery, was arrested and charged with their murders nearly five months later. Those months waiting for an arrest were agonizing, Englund said.

“You know, your mind does really strange things when something violent like that happens and you don't have an explanation for it…I wouldn't even go outside and start my car because I kept thinking, ‘What if somebody's after my family? What if I go out to my car, and someone's gonna knock me over the head and kill me?’ Your mind just does the most bizarre things,” she said. “And we just needed to know because I thought I was losing my mind. I think I'm pretty well grounded. But during that period it was insane how it can create so much trauma for your brain."

So how did law enforcement track down Wells?

Smith had few words to describe the process: “Damn good police work.”

After Wells pleaded not guilty to the murders and his trial began, Englund said her family was present, but not her father. It caused him too much pain, she said. And when Wells was found guilty, her father died before he could be sentenced.

He never knew his son’s killer was given the death penalty.

In Idaho, every person sentenced to death is given an automatic post-conviction appeal to the district court and a hearing within 90 days of the appeal. Of course, Wells was able to file his appeal. But that’s when something out of the ordinary happened.

In 1993, Wells asked to drop all of his appeals so he could be put to death, the Associated Press reported. Englund said she wasn’t shocked at the time.

“It was selfish on his part. He had mentioned to someone that he didn't want to sit in a cell for 20, 30, 40 years if he's on death row with a chance you might get executed… Maybe in Idaho, but you still might sit there ‘til you die,” she said.

Wells was scheduled to be executed around midnight on Jan. 6, 1994. Reporters, people from the governor’s office, police and prison staff all crowded inside the viewing room for the execution. Englund wasn’t there – there were too many people inside – but she was watching the news, along with a few Boise Police officers who had decided to stay with the family that night for a sense of comfort.

A phone call

An hour before Wells’ would lie down and the lethal injection needle would be administered, he told his spiritual advisor he wanted to pass along a message to the victims’ families – but he didn’t know how to do it.

The spiritual advisor immediately thought of one person who may be able to spread that message, and that was KTVB anchor and reporter, Dee Sarton.

Sarton told KTVB she had just put her children to bed when her phone rang around 11 p.m. On the other line was her friend, a pastor who was advising Wells before his death. He relayed to her that Wells would like to have a conversation – and she agreed to it.

“It was a short conversation,” Sarton said. “He sounded very sincere.”

However, she added, it was not very emotional.

Wells wanted the families to know he was sorry for his actions, and was asking for forgiveness even though he knew he didn’t deserve it, Sarton said.

Once Wells hung up, Sarton raced to the news station, where she was thrown on set to relay what had happened during the phone call.

“Any time you come that close to death… It has a profound effect," Sarton said. "We often push death to the side… What would it really be like to know you’re going to die? It was a very thought-provoking experience.”

Looking back, Sarton said, she felt privileged to be in that place as a journalist.

However, Englund just wanted the entire process to be over. For many families of victims, that doesn’t ever end. Out of the eight people on Idaho’s death row, the average time they’ve spent waiting for execution is around 27 years, counting the first death sentence that was given to Thomas Creech -- he has spent 47 years off and on Idaho's death row, the longest in the state.

To Englund, this means a long, painful process for the people who wait for an end to the pain they’ve endured with the death of a family member.

A death penalty case

First-degree murder in Idaho can carry a penalty of death. For the four murdered in Moscow, many on social media were speculating when the prosecution in Latah County might file the notice of intent to seek the death penalty against Kohberger, if at all.

Kohberger’s trial is slated for Oct. 2, but now that it's a death penalty case, that very well could change. If imposing the death penalty is the goal, that may push the trial out further, due an additional burden the state must have to prove and prepare for. The defense has even asked for the judge to put a pause on the proceedings so they have time to contest Kohberger's grand jury indictment.

Under the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, anyone charged with a crime has the right to a speedy trial, but it doesn't set a time frame. Idaho law does: The trial must begin no later than six months after the defendant's arraignment in district court, which is usually the point at which the defendant enters a plea. However, a judge may postpone the trial to a later date if a defendant chooses to waive the right to a speedy trial or if attorneys on either side can show the court that there is “good cause” for a postponement.

Kohberger's defense attorneys have also been continually vocal about the media attention on the case, mentioning in a previous hearing that they don't want to "whip the media into a frenzy." The news of the case has even stretched as far as the United Kingdom, which could make finding a jury for a death penalty case that much harder due to bias from previous media exposure.

Wendy Olson said at a hearing for Kohberger on June 9 that she would be “stunned” if the case went to trial on Oct. 2.

In that sense, the defense also has to prepare “a death defense” which can take much longer as well – according to the American Bar Association, capital attorneys must hire their own investigators, consult with experts, conduct a mental health evaluation from a psychologist and also spend time evaluating the evidence the prosecution has.

This also takes significantly more funds.

Ada County Judge Steven Hippler said there is a statewide Capital Crimes Defense Fund, which pulls money from each county. To be a part of the fund, it requires a $10,000 deposit from said county. If that county seeks the death penalty against a defendant, they can access those funds and then some.

Death penalty cases are a long process. The decision to file the death penalty is under the discretion of the prosecutor, according to Hippler.

“The prosecutor can rely on a number of different things…What is the family's position, does the family want the state to pursue the death penalty? I don't want to speak for the state, but I would imagine that they take into account the circumstances of the homicide. The victim was a child, for example. Were there multiple victims?...And I suspect they also weigh into the determination the likelihood that the death penalty would ever actually be carried out,” Hippler said.

LaMont Anderson, lead counsel for the Idaho Attorney General’s Capital Litigation Unit, said from the very beginning of even considering the death penalty, prosecutors have to “have pretty good evidence supporting that first-degree murder to get the conviction.”

Anderson has worked on death penalty litigation for 25 years – and could likely tell you every name of someone put to death in Idaho and those remaining on death row.

Prosecutors in a death penalty case have to prove “aggravating circumstances” beyond a reasonable doubt, which Anderson said may be what prosecutors also consider when looking to file the death penalty.

These circumstances can be proven during trial, but a jury will have to decide on that during the penalty phase, which is deciding whether or not the defendant should be sentenced to death.

“I think it's incumbent upon prosecutors to actually do part of the defense job for them. And… What kind of mental health evidence is the defense going to present? I think that those kinds of factors, those kinds of issues have to be factored into the question of whether you seek the death penalty or not,” Anderson said.

In 2002, the United States Supreme Court ruled that juries must be the ones to find the existence of aggravating circumstances in a death penalty case because they are "the functional equivalent of an element of a greater offense.”

“That's an additional burden of proof. Even if they prove an aggravating circumstance in which the death penalty could be imposed, then they go to a penalty where the sentencing is actually done by a jury. And in Idaho, you have to have a unanimous jury return a death sentence. It only takes one person to decide to spare the defendant’s life. And that's an extraordinarily high burden for the state,” Hippler said.

The jury during the “guilt phase” of the trial would be the same jury to decide to put a defendant to death. That jury only has to find that one of the aggravating circumstances in the case exists in order to sentence the person to death – and those circumstances could consist of many things.

So what are aggravating circumstances?

According to Idaho law, prosecutors have to prove one or more of these:

- The defendant was previously convicted of another murder

- The defendant committed another murder at the time of the crime

- The defendant knowingly created “a great risk of death to many persons”

- The defendant committed the crime for promise of money or a service or employed another with promise of money or a service

- The murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel, manifesting exceptional depravity.

- The defendant exhibited utter disregard for human life during the manifestation of the crime

- The murder was committed during or an attempt of an arson, rape, robbery, burglary, kidnapping or “mayhem” and the this person killed, intended to kill or acted with “reckless indifference to human life.”

- The defendant, by their conduct, exhibited a propensity to commit murder that will be a continuous threat to society

- The murder was committed against a former or present peace officer, executive officer, officer of the court, judicial officer or prosecuting attorney

- The murder was committed against a witness or potential witness in a criminal or civil legal proceeding because that proceeding

The jury in a death penalty case has to tell the court which aggravating circumstance(s) they have found to exist within the case, if any.

Once a jury finds those circumstances exist, the penalty phase of the trial ensues. This penalty phase is where the jury will weigh those aggravating circumstances and the evidence presented during the trial to decide if the defendant should be put to death – but, like Hippler said, it only takes one person to spare the defendant’s life. If that happens, the defendant receives an automatic sentence of life in prison.

However, in the penalty phase, the defense has an option to prove what courts call “mitigating circumstances,” Anderson said.

These mitigating circumstances usually consist of mental health evidence, which can get “very very complex,” he said.

Other mitigating circumstances, which would be presented by a specialist, include family history, behavioral history and other pieces of the defendant’s life that could be used by the defense to persuade a jury to recommend against a death sentence.

“The state has an opportunity to try to refute that mental health evidence…Those statutory aggravators still have to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. The mitigation has to be weighed against these statutory aggravators, and then a jury makes a decision,” Anderson said.

When someone is sentenced to death in Idaho, they are ordered to die by lethal injection. But, Anderson said the chemicals are so hard to come by that Idaho can't obtain them in order to execute anyone on death row. The Idaho Legislature passed a bill in the 2023 session to bring back the firing squad as a means to compensate for the lack of lethal injection drugs and the bill was signed by Gov. Brad Little on March 24.

It is unknown when the firing squad facility would be completed, as it would take time to build. KTVB reached out to the Idaho Department of Corrections for comment, but they declined.

Appeals can take years

When a defendant is sentenced to death, they are entitled to file for post-conviction relief within the trial court, Anderson said, which allows them to raise issues of constitutionality or mistakes in trial in hopes a judge will overturn the sentence or conviction itself.

Attorneys must review every single word from the trial and conduct their own investigation.

“It takes years to get through that process,” Anderson said.

The defendant can also directly appeal to the Idaho Supreme Court at the same time they filed for post-conviction relief.

If one or both are denied by the Idaho Supreme Court, the defendant can file for a writ of habeas corpus, which is similar to post-conviction relief, but filed in federal court.

Part of the problem, Anderson said, is that Idaho just doesn’t have enough federal judges.

“We have two federal judges, as in federal district judges, and only district judges can handle capital cases…Our federal judges are already overworked with all of their other stuff, and so when you add the burden of a capital habeas case on on them, it's an enormous undertaking,” Anderson said.

An undertaking that a judge can spend many, many years on.

“(A judge) has to go through and determine which of the claims in the petition were actually raised in state court, because if they weren't properly presented to the state court, they're procedurally defaulted…Once you get through that, then (a judge) has to get to the merits of the claims and go through all of that,” Anderson said.

Eventually, a defendant’s case could reach the U.S Supreme Court, but that would be a last resort.

In 2014, the Office of Performance Evaluations for the Idaho Legislature issued a report about the research they had done on Idaho's death penalty system. In their report, they stated for those who went to trial, reaching a judgment by a jury took seven months longer for capital cases than for noncapital cases.

And, the death penalty in Idaho is rare -- few people are sentenced to death, and fewer are executed, the report states.

Anderson said the stacks of paper he has on each death penalty case in Idaho is “becoming a problem” just due to the length of time each case has taken to travel through the justice system.

“I have banker's boxes, literally, banker's boxes of files that start from the time that someone is indicted or charged with a capital crime, all the way through the federal court system that take up anywhere from upwards of 30 to 40 boxes,” he said.

Anderson would love to find a way to speed up the process for those waiting to be executed on Idaho’s death row.

Currently, eight people remain. Idaho has only executed three people since 1976, when the U.S Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty after a long debate on the constitutionality of executions.

“I've had conversations with victims about why the process takes so long. They want things done quickly, but that can't always be the case. We want to make sure that these individuals receive due process,” Anderson said.

Even as a litigation attorney, Anderson said the cases themselves can still be emotional. Sometimes, he does quite a bit of self-reflecting.

“There are good days, there are bad days doing my work. Days that I wonder why I'm doing it, particularly considering the delays that are associated with it,” he said.

Englund, who said she never even thought about the death penalty until her brother was murdered, said she believes it’s “a flawed system.”

“There's a lot of things that need to be changed. And first off, either execute in a timely manner, or don't even have it as a punishment,” she said. “I don't know if (the system) is ever going to be perfect.”

Thirty-three years ago, Englund said, she probably wouldn’t have even known anything about the death penalty. But losing her brother completely changed her perspective.

“I told somebody I was doing this interview, and they said, ‘Oh, so you're for the death penalty?’ And I said, well, I am not afraid to say that I am,” Englund said.

“Don't tell people they have closure, because we don't… I think they'd like to think once the person is caught and convicted and sentenced, it's over with," she said. "But it's not over for the families."

KTVB’s award winning investigative team reports on local, crime, and breaking news across Idaho.