Interstate Bridge replacement costs and project scale come into focus as Oregon considers how to fund it

Oregon is being asked to kick in $1 billion for the $6 billion megaproject, and lawmakers are taking a fresh look at the cost of each piece of the plan.

There’s a plan taking shape in the Oregon Legislature to set aside $1 billion to fund the state’s portion of the $6 billion cost of replacing the aging Interstate 5 Bridge, but the process is renewing debates about the size and scope of the planned project.

Lawmakers Oregon’s Joint Transportation Committee have signaled that they’re likely willing to put up the money, but they want to know more about what exactly they’re buying. An initial hearing on April 13 outlined some details about what the replacement bridge will look like, how it will be built and how much each piece of the project is going to cost, and those details are likely to take center stage at a follow-up public hearing scheduled for Thursday afternoon.

First, a quick recap on the bridge design. Around this time last year, the Interstate Bridge Replacement project team released what’s called the Locally Preferred Alternative, which laid out their recommendations for some of the broadest details about the project, based on public feedback and input from local governments and agencies.

Here’s what they decided:

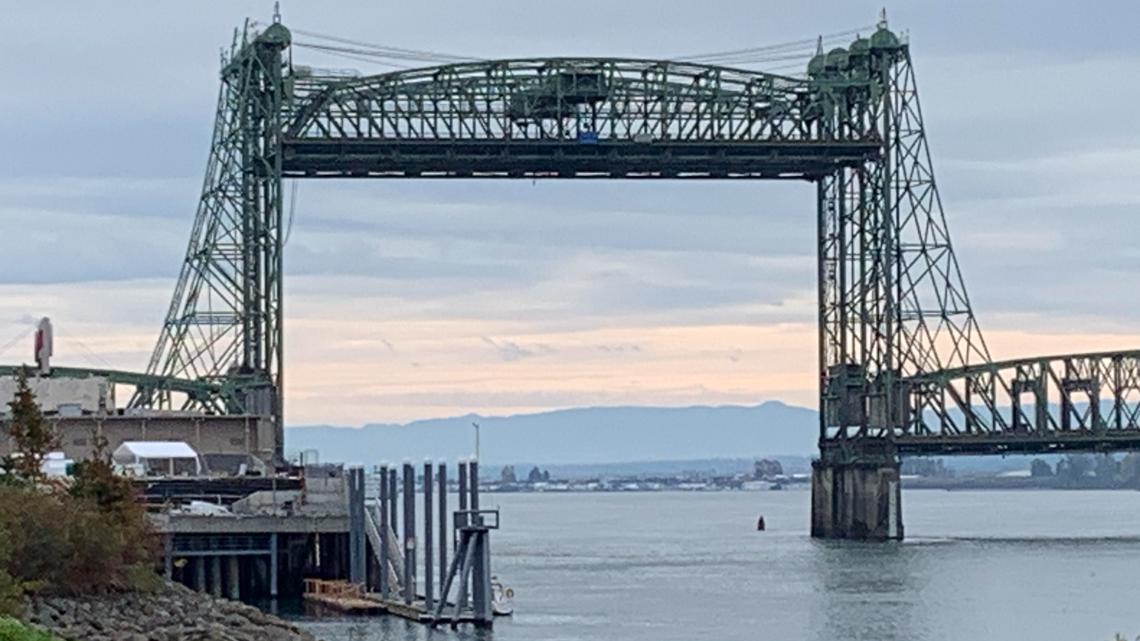

- The bridge should be a fixed crossing, which means it doesn’t move. That means no more drawbridge and no more traffic stuck waiting on I-5 during bridge lifts.

- It should have four lanes in each direction, for a total of eight. The current bridge has six lanes total, and the old Columbia River Crossing plan was going to have ten, so the IBR plan splits the difference.

- It should include light rail, extending the MAX Yellow line to downtown Vancouver.

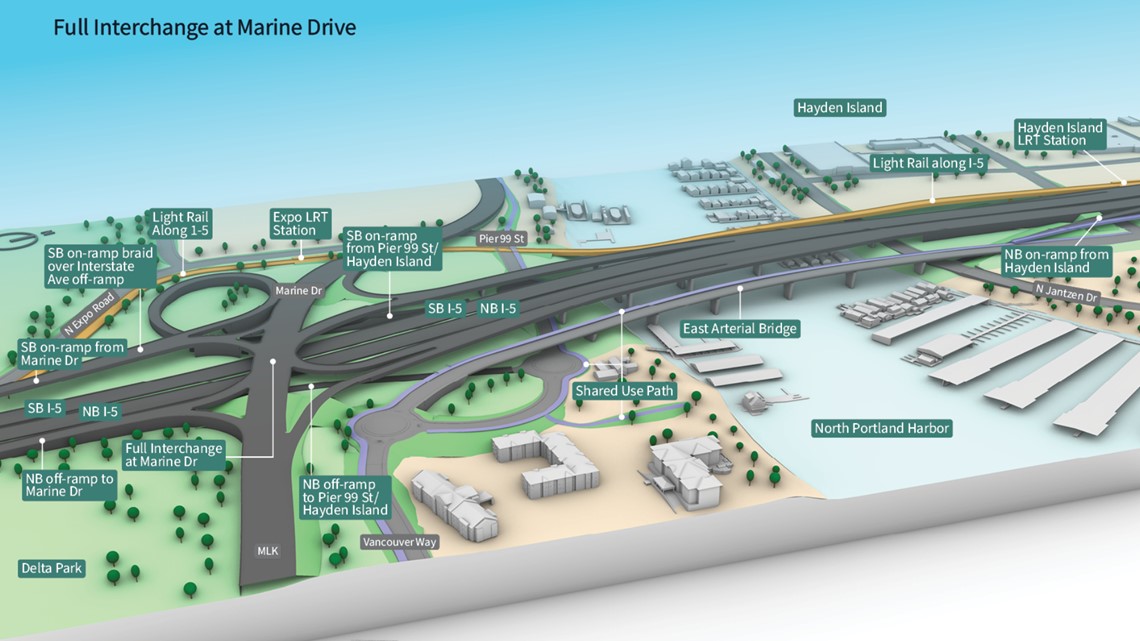

- It should shrink the interchange on Hayden Island so it only serves traffic from the Washington side of the river. Oregon drivers would reach the island on new local bridge, separate from the freeway.

Lift spans and lanes

With the locally preferred alternative in hand, the IBR team began to put the project through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process – the federal evaluation and approval system for big projects like this. That process is still ongoing, but some wrinkles have already emerged.

The U.S. Coast Guard isn’t thrilled about the proposed 116-foot height of the new bridge, because it would have about 60 feet less clearance for river traffic than the current drawbridge. The Coast Guard hasn’t outright vetoed the fixed span design, but the agency did ask the IBR team to also study a drawbridge option during the NEPA process.

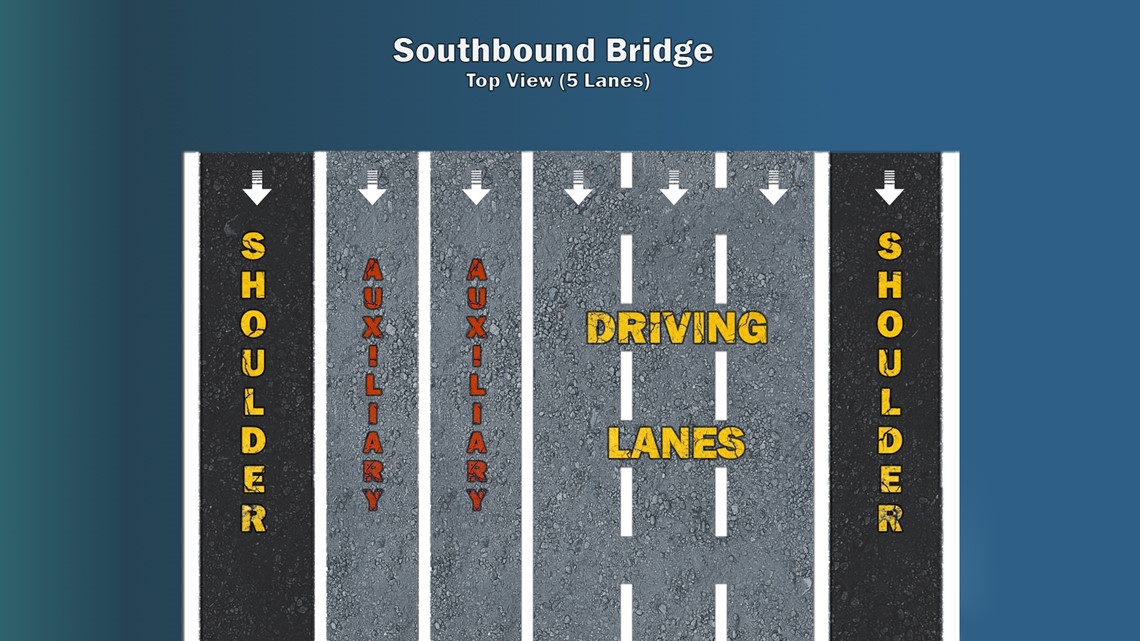

And there’s another piece that’s gotten a little murkier: The Locally Preferred Alternative settled on eight lanes total, but the Columbia River Crossing’s ten-lane configuration seems to have snuck back into the mix. Johnson confirmed at the April 13 hearing that the team is studying both 8-lane and 10-lane versions as part of the NEPA process, with a final decision still to come.

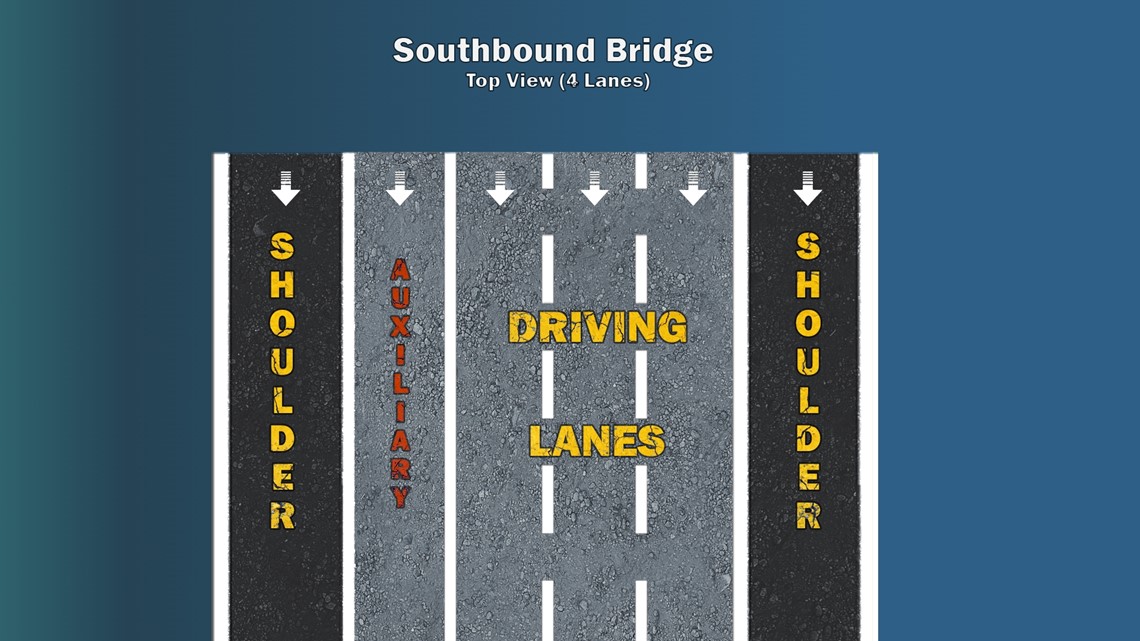

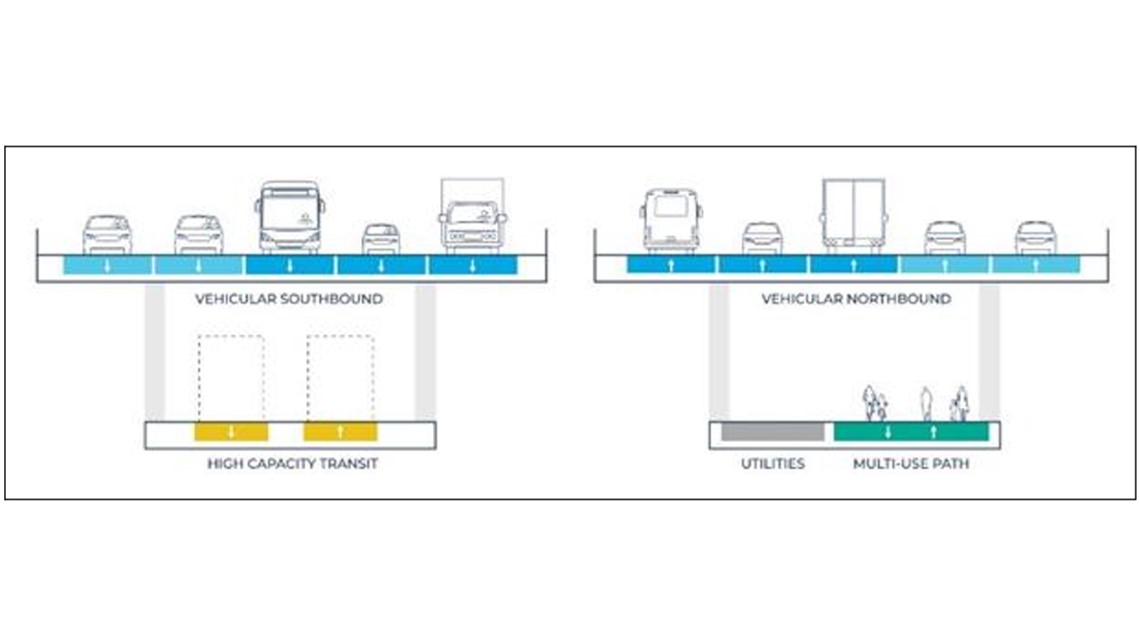

There are some additional details that are looking increasingly certain, the foremost of which is that no matter what version we end up with, the replacement bridge is going to be a twin span structure, just like the current bridge. That means it’s technically going to be two bridges side by side: one for southbound traffic and light rail and the other for northbound traffic and a bike and pedestrian path.

IBR program administrator Greg Johnson said it’s become clear in the past year that a single bridge just wouldn’t be practical.

“Once you get that wide having one bridge, you get limited to the type of bridge you can construct,” he said. “So we want to make sure we're giving any contractor some flexibility in bridge type to save us dollars in the future.”

Complicated Construction

The twin spans design will also help with construction because they can be built one at a time, and Johnson said that's probably what the IBR project will end up doing. The tradeoff of that added flexibility is that the total construction timeline could be as long as eight years.

“Because we're maintaining traffic on the existing bridge, we're going to build approximately a 100-foot gap and build one of the new bridges… shift traffic to that, and then build the second span, which may have some overlap with the existing bridge, so there'll be part of that old bridge that may have to be taken out sometime probably in the 2030, 2031 timeframe to accommodate that second new bridge,” Johnson explained.

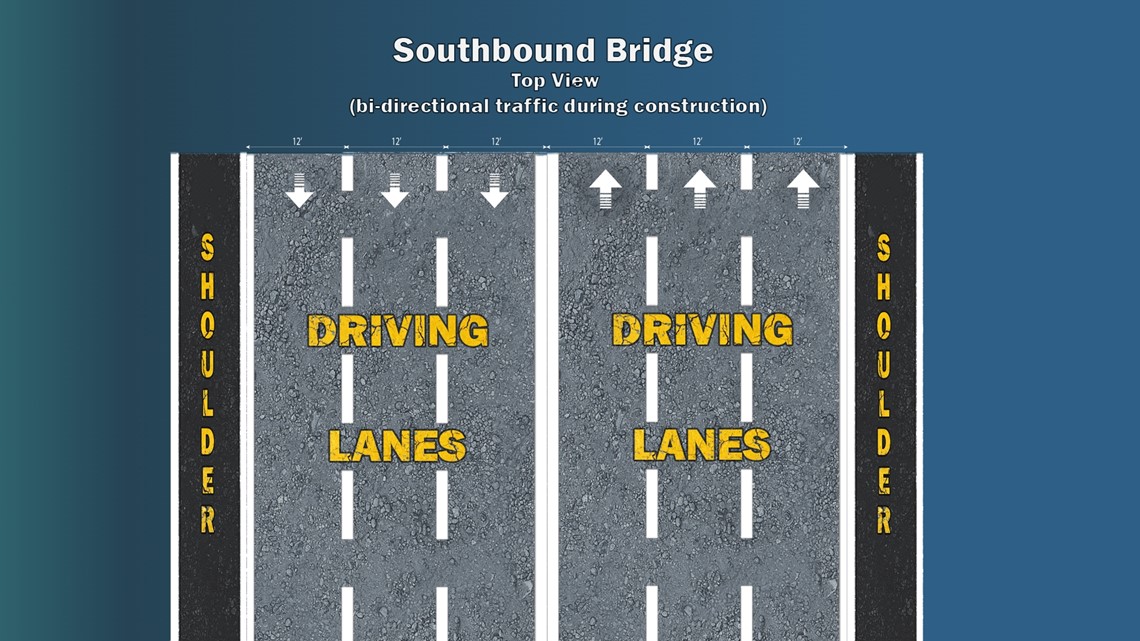

And to be clear, shifting traffic to the new bridge means shifting all I-5 traffic, both northbound and southbound.

Construction would start on the southbound span and some preliminary work on the northbound span in 2026, with traffic shifting over from the original bridges to the southbound span in 2030 or 2031. Then the old bridges would be demolished and the second new one would be built, with northbound traffic shifting back over to the second new bridge between 2031 and 2033, according to Johnson.

That means there will be a couple of painful years when all of the traffic is crammed onto one bridge. That’s part of why the light rail line is going to be on the southbound span, Johnson said, so it can be completed before the crunch period.

“If we can get light rail up and running, we will have another relief valve for folks who don’t want to sit in the traffic,” he said.

The question of width

The current bridge has three lanes in each direction, so compressing all of that down to a single bridge with four lanes sounds like it would make things even worse, but according to Johnson, it might not be quite that bad. In order to explain why, we’ve got to tackle another topic: width.

The width of these structures came up during the recent hearing in Salem, including a lengthy back and forth when Rep. Khanh Pham (D-Portland) pressed Johnson to give a specific number for the bridge’s total width.

We double checked with Johnson, so let’s break down the answer:

A standard freeway lane is 12 feet wide, and each span would have either four or five of them. Each span is also going to have 12-foot or 14-foot shoulders on each side, according to Johnson – the possible extra two feet is because the team is looking at having the inner shoulders double as bus lanes.

That all totals up to 76 feet per span, or 152 feet total, not counting the gap between the two spans. Add in the extra pair of lanes and it would be 88 feet per span, and 176 feet total.

For a real-life visual reference point, the Interstate 205 Glenn Jackson bridge has four lanes with inner and outer shoulders on each side, and it’s a bit less than 150 feet wide.

That 76 feet of width is just enough to squeeze in six lanes during the construction phase if most of the shoulder space is temporarily used for regular traffic. That’s essentially what the current I-5 bridge does – each span is about 39 feet wide and has three lanes and no shoulders.

It’s worth noting that those width figures don’t account for light rail tracks or bike and pedestrian space, and that’s because those parts may end up getting tucked away on lower decks. That was the plan back in the Columbia River Crossing days – twin spans with light rail underneath the southbound freeway and a bike and pedestrian path underneath the northbound freeway.

But that’s not yet a sure thing this time around, Johnson said. Everything could still end up on one deck, in which case the width of each span would be 76 or 88 feet plus the width of two light rail tracks or a bike and pedestrian path.

“Both are still on the table,” Johnson said. “We're going to look at the benefits and the drawbacks and tradeoffs of each scenario. And that’s some of the things that we're going to be asking the public to weigh in, as we work towards getting our draft supplemental document out towards the end of the year.”

Breaking down the bill

The design is one half of the current discussion in the legislature, and money is the other. The IBR team’s latest estimate in December put the total cost of the project at a range of $5 billion to $7.5 billion, with $6 billion as the most likely number. But Johnson’s presentation at the April 13 hearing included what you might call an itemized bill, listing out the costs of the different pieces of the project.

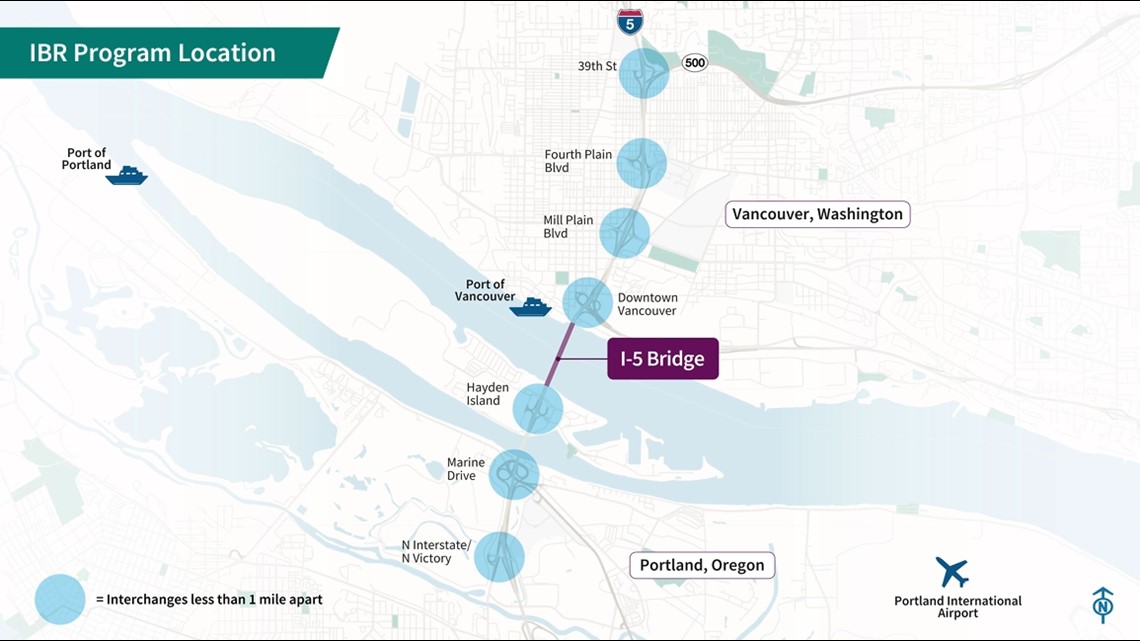

The bridge alone is about $1.5 billion to $2.5 billion. But the IBR team’s plan also calls for rebuilding or upgrading seven of the surrounding I-5 interchanges – four on the Washington side and three on the Oregon side, plus the extra local bridge from the Oregon side to Hayden Island.

The Washington side upgrades are about $1 billion to $1.5 billion, and the Oregon side upgrades are about the same amount again. Finally, the light rail extension and new stations will run about $1.3 billion to $2 billion.

And that’s all for the Locally Preferred Alternative version – as in 8 lanes and no drawbridge. Speaking to state lawmakers earlier this month, Oregon Department of Transportation director Kris Strickler said switching to a drawbridge design could raise the price tag by up to $500 million. And adding the extra two lanes would raise it by anywhere from $100 million to $250 million, according to Johnson.

The IBR team’s funding plan calls for Oregon and Washington to each kick in $1 billion dollars and the federal government provide, optimistically, at least $2.5 billion, with the remaining $1 billion or more paid through tolls.

That’s a lot of money, and Oregon lawmakers seem interested in finding a way to keep that bill from running any higher. The draft legislation being considered by the Joint Transportation Committee includes a provision stating that the overall cost of the project “may not exceed 6.3 billion dollars.”

The legislation isn’t final yet, but the cap provision appears to be serious. Committee co-chair Rep. Susan McLain (D-Hillsboro) was one of the ones who drafted the plan, and she told KGW earlier this month that she specifically sought to include the cap.

Looking for cost savings

When asked about the idea, Rep. Pham said she not only supports the cap, but wants it to have more teeth. She said that’s also why she was pushing so hard to nail down the width – she’s concerned about the scale and costs of the project creeping upward.

“My ideal version is just building the I-5 bridge replacement. That's the name of it. We should replace the I-5 bridge,” she said. “We should build great public transit on the bridge so we have a climate friendly alternative – and that's it. But I don't think we need to add on these freeway onramps, multistory onramps, that are going to be both very expensive – it's half the size of the project, is actually these freeway approaches.”

Greg Johnson argued that the freeway interchanges can’t be easily cut from the project, in part because any version of the new bridge will need to be higher than the old one. A fixed bridge needs to be higher to maintain river clearance, and a drawbridge will still need to be higher in order to decrease the number of times it will need to lift.

But I-5 ducks underneath a railroad line just before the start of the current bridge, which means the freeway can’t be raised just a little bit – it has to be high enough to go over the top of the railroad line, which makes rebuilding the Highway 14 interchange on the other side of the rail line unavoidable.

But while that explanation might make sense for the Highway 14 interchange, critics have also taken aim at some of the other interchanges in the project zone, some of which are more than a mile down the road from the bridge itself.

The idea of cutting light rail also came up at the hearing, but Johnson replied that about $1 billion of the federal funding the team hopes to line up for the project would be from the Federal Transit Administration, which essentially means it would be for light rail specifically.

And the inclusion of light rail could also increase a separate federal pot of money for the bridge itself, Johnson said, so yanking that component out of the project wouldn’t necessarily be a large or clean cut.

Oregonians weigh in

Public scrutiny of the scale and cost is good, Pham said, because now is the time when Oregon has the greatest leverage to influence the scale of the project. Once construction is underway, it gets much harder to hit the brakes or scale down if things go over budget.

“We need to make sure we’re right-sizing the design so we’re not stuck halfway, with a halfway overbuilt project, because we all know once it’s, once we start building a bridge, it’s very difficult to change course or to stop building it, obviously nobody wants to do that,” she said.

Of course, not everyone in the legislature agrees on what a right-sized bridge looks like – Rep. Kevin Mannix (R-Keizer) said at the hearing that he’d rather see the project go all-in with the 10-lane configuration – but there does seem to be a shared recognition that if Oregon wants to haggle over specific pieces of the project, now is the time to do it.

There’s urgency outside of the legislature as well. The Joint Transportation Committee is scheduled to hold a public hearing on the finance plan Thursday afternoon, and local advocacy groups like No More Freeways and the Just Crossing Alliance have been urging their members to show up and voice support for a revised plan with a smaller-scale project and stronger financial guardrails.

And if you’re wondering when the final decisions will be made on all these variables, the answer is next year. Johnson said the team wants to have a draft NEPA plan out for public review by the end of this year, and then narrow things down to a final version that would hopefully get a federal green light by the end of 2024.