PORTLAND, Ore. — With the November midterm election little more than a month away, political candidates and their campaigns are doing everything in their power to get and hold the public's attention. Whether you're trying to consume media on television or online, it's nearly impossible to miss the political ads — which is precisely the idea.

The strategies are designed to get voters to believe that a candidate is their best friend, that they understand constituents and have their best interest in mind. But their opponent? Electing the opposition will effectively bring about the end of the world, or so they'd have you believe.

On Tuesday, KGW aired an ad by a political action committee supporting democrat Tina Kotek for Oregon governor. The advertisement aims to sour voters on both of her opponents. It's just one of many that you will see in the weeks ahead, according to Republican campaign strategist Rebecca Tweed.

"Good luck avoiding ads right now. I was watching TV last night and football all weekend and saw ad after ad after ad," said Tweed. "And of course I love them. But if I were a regular voter it would seem like a lot.

"What's really important here is that the candidates and their campaign strategists try to find a way to make these ads stand out. And that becomes more and more difficult with candidates and campaigns spending more money and being more accessible. I’ll be really interested to see the direction some of these advertisements go — you know, do they get more negative? Do they get more kitschy? How do they really draw themselves apart?”

In at least a few of the local campaigns, the answer is clear: they're getting nasty.

A KGW viewer named Marina asked if there were any studies that demonstrate if negative political ads really work.

"The more vicious the ad the more I'm inclined to vote for the other candidate!" Marina wrote.

There is data to suggest that these kinds of ads are effective. A study from the University of California in 2019 cites professor Alison Ledgerwood at UC Davis. She found that the "framing" of an idea or issue, the way it is presented, can determine whether you remember it. Presenting something in a negative frame has more staying power than a positive frame.

Human brains seem to be hardwired to recall negative information. Political operatives know that, and they sometimes come up with catchy negative phrases to drive home their message.

The report serves as a reminder of many examples through the years; for example the epithet for President Richard Nixon, "Tricky Dick." Ads and partisan messaging associated "death panels" with the Affordable Care Act. And of course, President Donald Trump had a long list of negative phrases or names for his opponents and critics, from "Crooked Hillary" to "Lyin' Ted" and the liberal use of "fake news."

Even if negative messaging of this kind is inherently distasteful as Marina suggests, it's clear that the strategy can be effective.

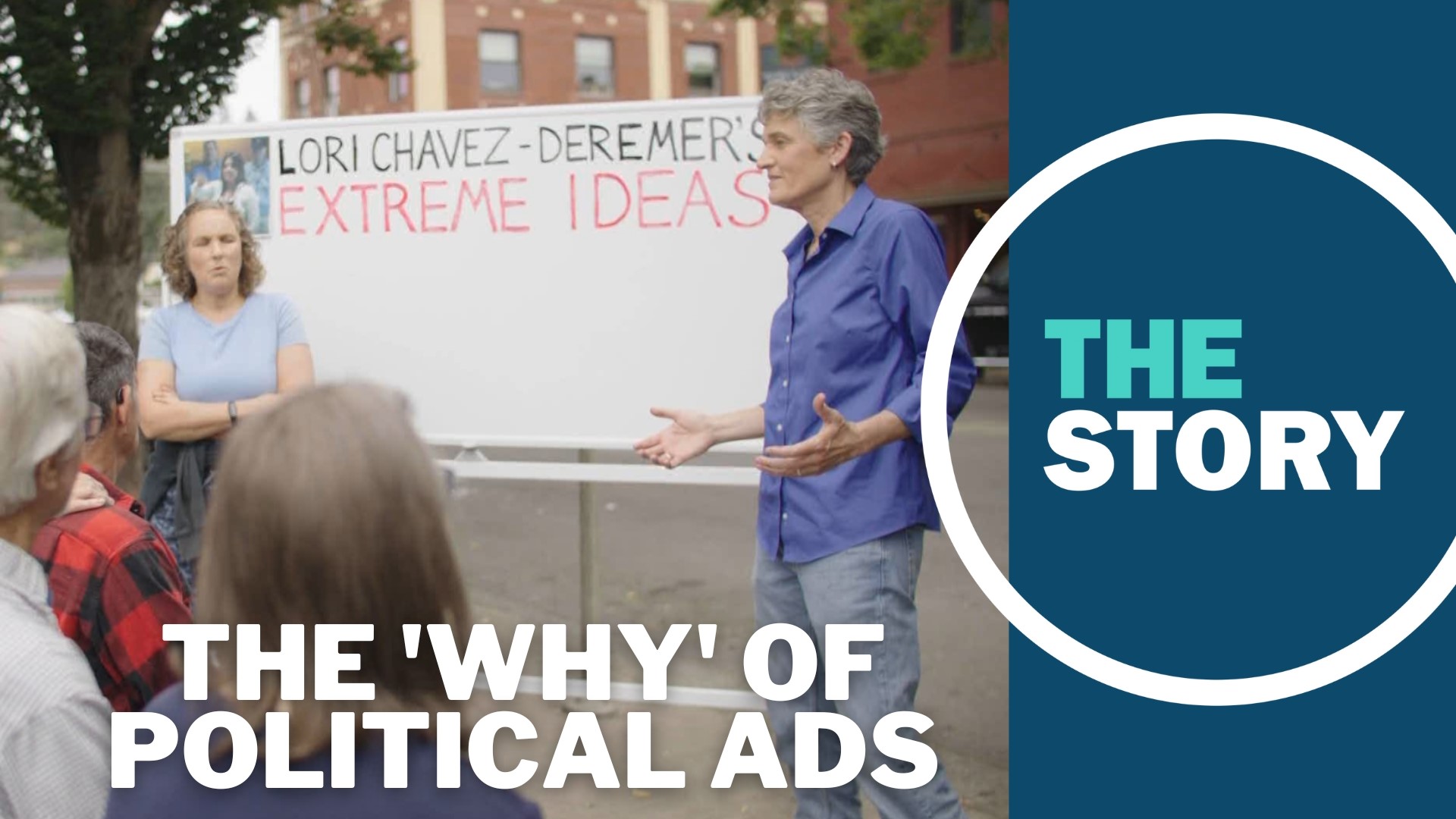

This strategy is why voters may have seen ads from Jamie McLeod-Skinner featuring negative words written on a white board about her opponent, Lori Chavez-DeRemer. McLeod-Skinner's campaign is banking on voters remembering those words — to the exclusion of basic details. The ad never mentions what seat in Congress she's running for or to which party she belongs. McLeod-Skinner is a Democrat running for Oregon's 5th Congressional District and Chavez-DeRemer is her Republican opponent.

Garrett, another KGW viewer, wrote in to ask about this apparent oversight in particular.

"Why aren't political ads stating their party?" Garrett asked. "Are they ashamed of their party or expecting voter stupidity?"

According to Rebecca Tweed, the answer to each question is "no."

"Well, when folks get their ballot they’re not reading it position by position as much as they’re reading it by name recognition," Tweed said. "And so there’s sorta two strategies. One is make sure your name is heard the most and the loudest and the most often, so that when people their ballot and that huge voter’s pamphlet statement they just say, ‘Oh, well this is the candidate I’ve heard the most, I’ve seen the lawn signs, there’s letters to the editor, I met 'em at the fair.'”

Based on these examples, it's easy to get at least an overall impression of what these ads are all about: recall and context. Each candidate wants voters to remember their name in a positive context, while only associating their opponents with something negative.