On Nov. 6, Oregon voters will decide the fate of Oregon's 31-year-old "sanctuary state," anti-racial profiling law.

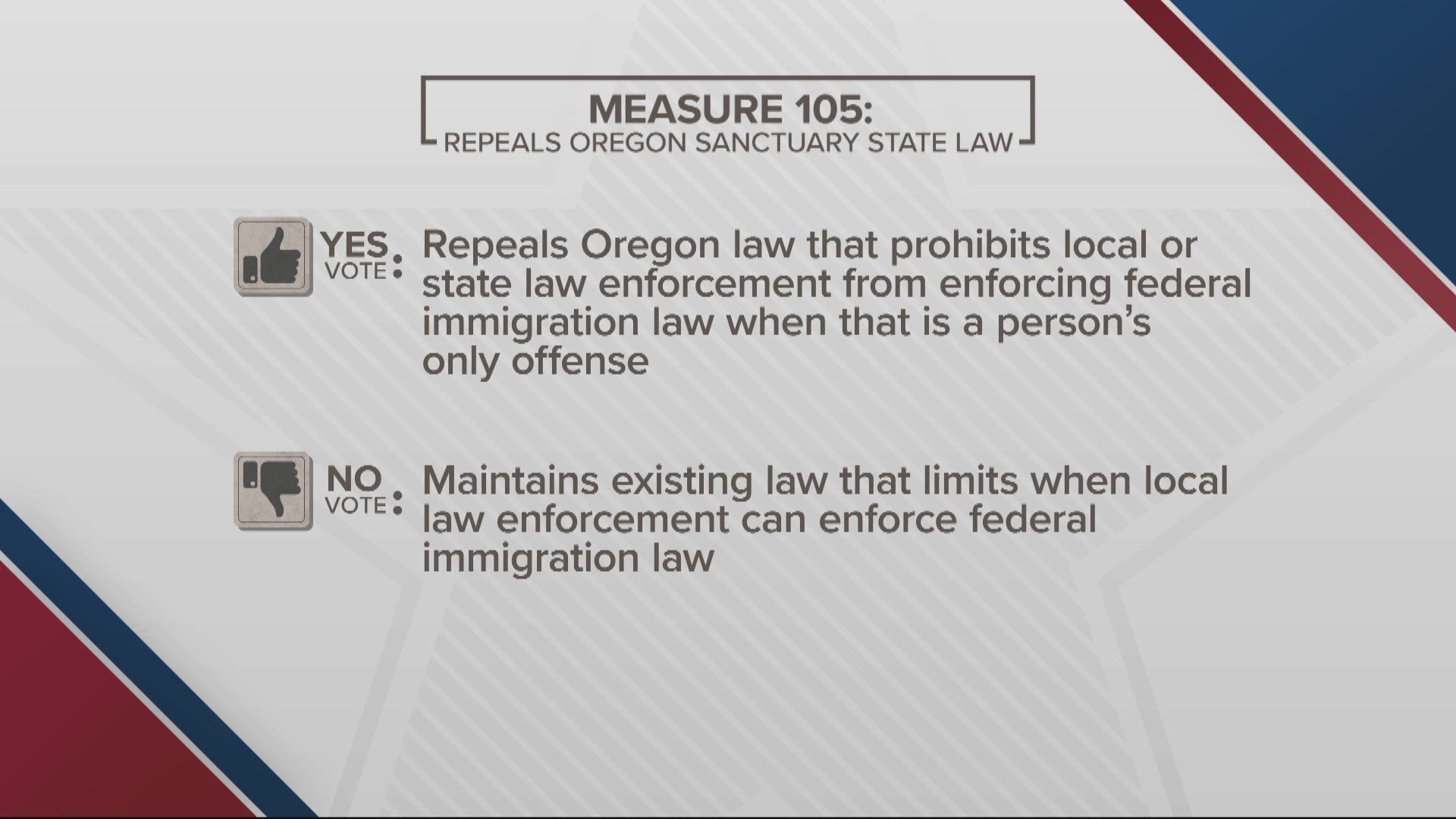

A "yes" vote on Measure 105 is a vote to repeal the law. A "no" vote keeps it in place.

Proponents claim the sanctuary law emboldens undocumented immigrants to commit crimes and ties the hands of law enforcement.

Opponents say the law prevents racial profiling, saying if the law is repealed, immigrant communities and people of color will feel unsafe and too frightened to report crimes to police out of fear of deportation.

The fight over the measure has been contentious, with both sides trading barbs and accusing each other of fearmongering.

(Story continues below)

Find results here as soon as the polls close!

Proponents claim anti-Measure 105 groups want to give undocumented immigrants who commit crimes special protections.

"The protections for people that are here illegally are absurd," said Cynthia Kendoll, president of Oregonians for Immigration Reform. "The frustrations that Oregonians have over this is almost palpable. Folks are so fed up with being second-class citizens in their own country."

But the other side says backers of the measure spread misinformation and stereotypes about immigrants and are connected to a hate group.

"I think what the proponents are doing is stoking fear and spreading false stereotypes about our Latino communities, and I think that's wrong," said Andrea Williams, executive director of Causa and leader of Oregonians United Against Profiling. "What they are saying is completely misleading and false."

More than a million dollars in contributions have poured into the fight.

According to Oregon Secretary of State records, Oregonians United Against Profiling has received $1.67 million in contributions. The Repeal Oregon Sanctuary Law Committee has received $48,534.

And with President Donald Trump promising to build a border wall along Mexico and decrying the "bad hombres" and gang members crossing the border, Oregon's debate couldn't be more timely.

Showdown at the Hi-Ho Restaurant

Oregon's law — the first sanctuary state law in the United States — traces back decades to a long-closed restaurant in a small town outside Salem.

In January 1977, Delmiro Trevino, a U.S. citizen of Mexican descent, was eating with his friends at the Hi-Ho Restaurant in Independence when he was approached by an Independence police officer and three Polk County sheriff's deputies, who grabbed his arm and interrogated him about his immigration status.

The officers relented after another officer identified Trevino as a longtime resident of Independence.

Embarrassed and angered, Trevino contacted Salem attorney Rocky Barilla, who later filed a class action lawsuit accusing the officers of acting on behalf of the federal Immigration and Naturalization Service, now known as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Barilla said back then, police were known for taking part in raids, questioning people who looked Hispanic and having a "wink-wink relationship" with federal immigration officials.

Ramon Ramirez, of Woodburn, co-founder of Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste, said that in the 1970s and 1980s, the immigrant and Hispanic community feared local police. Immigration raids and roadblock checkpoints were a daily occurrence.

"If you were Latino looking, you were pulled over," Ramirez said. "That was the reality back in the day."

When Barilla joined the Oregon Legislature in 1986, he sought to correct this distrust and fear in the community.

He co-sponsored a bill forbidding state agencies, including law enforcement, from using state resources or personnel to arrest people whose only crime was being in the country illegally.

The bill passed both houses almost unanimously and became Oregon Revised Statute 181A.820.

Barilla said the bill had significant support from both Democrats, Republicans and local police.

"All of us want safe communities," he said. "The police are not our enemy."

Ramirez said the difference in police-community relations today is stark.

He recounted a frightened teen waking up to see immigration officials trying to separate her parents from her young siblings outside her home in Woodburn. Not knowing who the people were outside her house, she called local police, who responded and helped sort through the chaos.

The person immigration officials were looking for no longer lived at the residence. The immigration officials left, and the family profusely thanked police.

The girl and her family trusted police enough to call them in their time of need, Ramirez said.

He said racial profiling continues today throughout the country, but added, "That law ... made a difference."

'We are actually making history'

Depending on who you ask, descriptions of Oregonians for Immigration Reform vary. Some claim its a white nationalist hate group. Others insist it's a grassroots organization bent on protecting Oregonians from criminals.

"We are just normal, mainstream people who are worried about our country and the direction that it's going in," OFIR president Kendoll said.

Kendoll made it clear the organization supports legal immigration, and she wishes no harm to people who cross the border illegally or overstay their visas.

"I don't want anything bad to happen to anyone here, but I find their disregard for the rule of law problematic," she said.

The manager for the pro-Measure 105 campaign, Kendoll previously worked against a measure in 2014 that would've allowed undocumented immigrants to obtain driver's licenses. Back then, she said the fight against the measure in liberal, deep-blue Oregon seemed like an uphill battle.

"Even our supporters were like, 'It's really cool what you're doing, but you're in Oregon. You're nuts. You're never going to be successful with this'," Kendoll said.

Despite being massively outspent, Kendoll's group prevailed. Voters struck down the measure by a large margin. More than 66 percent voted no, and the measure lost in 35 out of 36 of Oregon counties.

Their victory, as well as Trump's ascent to the presidency two years later, gave Kendoll and her group confidence.

After three chief petitioners, Republican state Reps. Mike Nearman of Independence, Sal Esquivel of Medford and Greg Barreto of Cove, brought forward a proposal to strike down Oregon's sanctuary state law, OFIR joined the fight, armed with accounts of murders and sexual assaults committed by undocumented immigrants and statistics on the financial burden they cause.

"People that are here illegally need to be removed from our state and country," she said.

The estimated 146,000 undocumented immigrants living in Oregon cost taxpayers more than a billion dollars in education funding, health care and law enforcement costs, she said.

Kendoll accused teachers unions, nonprofits and wealthy people with gardeners and nannies of protecting undocumented immigrants out of their own self-interest.

Kendoll also cited the case of Sergio Martinez, who brutally raped a woman and severally beat another in Portland in 2017. Martinez had previously been deported more than a dozen times. Kendoll said he never would've been able to commit those assaults if it hadn't been for the sanctuary state law and lack of cooperation between ICE and local law enforcement.

Opponents of Measure 105, however, argue against the connection between the sanctuary law and Martinez's case.

"What Sergio Martinez did is horrible and should never have happened, and he's being convicted of his crimes," Williams said. "The current law does not protect people like him."

Williams accused the measure's proponents of stereotyping immigrant as criminals and spreading false information.

"If you look at the FBI data, violent crime is at a near all-time low even as we continue to have immigrant communities in our state," she said. "Further studies have even indicated that undocumented immigrants commit crimes at lower rates than U.S. citizens."

Williams also pointed to OFIR's designation as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The law center deemed OFIR to be an "anti-immigrant hate group" due to its past partnerships with white nationalists and Minutemen groups and donations from organizations like US Inc., a nonprofit behind a white nationalist publication.

Kendoll called the claims baseless and said those donating and partnering with OFIR are "wonderful people who care about our country."

"I think the SPLC used to be a respected organization, but it has now devolved into a hate group," Kendoll said. "It seeks to malign any group or person who doesn't agree with their agenda."

Despite being painted as "mean-spirited, hateful white supremacists," Kendoll said Measure 105 proponents simply care about their country and want to uphold the rule of law.

"We're simply trying to give voters the opportunity to decide if Oregon should remain a sanctuary state or not," she said. "We are actually making history."

Fear of racial profiling

Kendoll argues that racial profiling of people living in the country legally is not a problem and that repeal of the law is not going to turn local law enforcement into "jack-booted thugs going out and breaking down doors and ripping nursing babies from their mothers' arms."

But Williams contends that fear of racial profiling persists in immigrant and Hispanic communities. The law was created for a real, pressing reasons, and it's been working well for the state, she said.

"This law is just as relevant today as it was back then," she said. "I work with immigrant communities every single day. I don't think you can say that about the proponents of this ballot measure."

The threat of repeal has many in the community concerned.

"Immigrant families we work with and even Latino families that have been here for generations are watching this measure very closely," William said. "They understand that this is one of the basic civil rights protections that we continue to have in this state and if you throw this out, we'll all be more vulnerable and we'll all be less safe."

Victims or witnesses worried about having their immigration status — or the legal status of a household member — questioned might be less likely to report a crime, she argued.

Williams pointed to data indicating that "show me your papers"-style laws have a chilling effect on crime reporting.

The Intercept reported that faced with a possible law banning sanctuary-style protections, Houston police saw a "nearly 43 percent decrease in the number of Hispanic victims reporting rape, even as rapes reported by non-Hispanics increased by 8 percent."

Williams said she understands that the immigration system is incredibly frustrating. But, she added, throwing out the sanctuary law will do nothing to address those frustrations.

"This is about preventing racial profiling and ensuring that all Oregonians, including immigrant Oregonians, can feel safe reporting crimes to police officers," she said. "It's about making sure local police have the trust of every Oregonian and especially those of immigrant communities that could fall victim to any number of crimes in our state."

What do police say?

Both Kendoll and Williams tout their strong support from law enforcement.

Kendoll points to an endorsement from the Western States Sheriffs Association and a letter penned by Clatsop County Sheriff Tom Bergin and signed by half of Oregon's sheriffs.

Bergin called claims that the repeal would lead to a wave of profiling of Hispanics "nonsensical and insulting to all the men and women who have sworn to preserve the peace."

Williams said the sheriffs who signed the letter represent less than 20 percent of the state population. Law enforcement leaders in the state's largest counties, including Multnomah, Clackamas and Washington counties, have spoken out against repealing the law.

Salem-area police, sheriff's offices and district attorney's offices have not taken a stance on the measure.

"As Sheriff and District Attorney in Marion County, we are not taking any official position regarding Measure 105," said Marion County District Attorney Paige Clarkson and Sheriff Jason Myers in a joint statement. "This is a matter for the voters to decide on November 6th."

Salem police officials echoed that sentiment.

"What we would like to express is how important it is for a community to know and feel they can trust their police department," Salem police spokesman Lt. Michael Bennett said. "Our success as an agency is dependent on a community willing and unafraid to contact the police when they see crime occurring or are themselves a victim of crime."

Polk County District Attorney Aaron Felton has not taken a stance, but added, "It is the mission of this office to serve our community by seeking justice without regard to politics, holding offenders accountable, and fighting for the rights of all crime victims."

Polk County Sheriff Mark Garton said if Measure 105 passes, it's not going to change much about how his department operates.

His office already communicates with ICE when needed. Any limitations about communication will still be in place even if the law is repealed.

He added that his department already trains annually, and sometimes even more, on racial profiling.

Racial profiling is just plain wrong, he said, and Oregon law enforcement is above it.

"We have higher standards," Garton said.

To him, a victim is a victim and a witness is a witness, and they deserve to be protected and respected regardless of their immigration status.

"We're not going to be going out and asking people for their papers," Garton said. "That's not what the taxpayers pay us to do."

For questions, comments and news tips, email reporter Whitney Woodworth at wmwoodwort@statesmanjournal.com, call 503-399-6884 or follow on Twitter @wmwoodworth

Oregon Election Guide: A look at several key races and measures