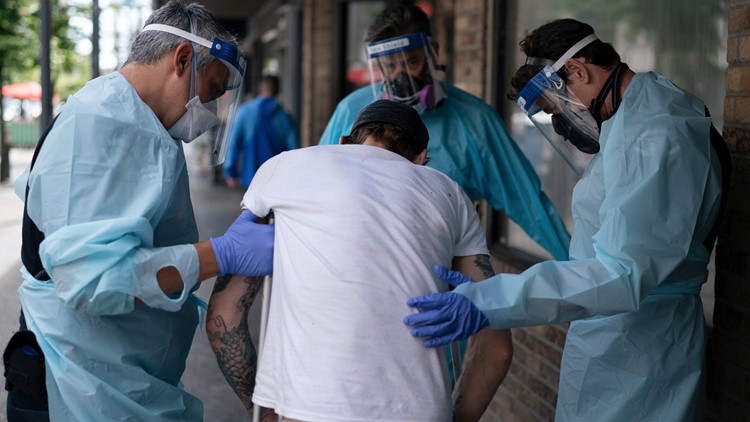

VANCOUVER, BC — Canada’s government said Tuesday it will allow British Columbia to try a three-year experiment in decriminalizing possession of small amounts of drugs, seeking to stem a record number of overdose deaths by easing fear of arrest by users in need of help.

The policy approved by federal officials doesn’t legalize the substances, but Canadians in the Pacific coast province who possess up to 2.5 grams of illicit drugs for personal use will not be arrested or charged.

The three-year exemption taking effect Jan. 31 will apply to drug users 18 and over and include opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA, also known as ecstasy.

“Stigma and fear of criminalization cause some people to hide their drug use, use alone, or use in other ways that increase the risk of harm. This is why the Government of Canada treats substance use as a health issue, not a criminal one,” tweeted Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer.

The province’s health officer, Dr. Bonnie Henry, said that “we are taking an important step forward to removing that fear and shame and stigma.”

“This is not one single thing that will reverse this crisis but it will make a difference,” she added.

Dana Larsen, a drug policy reform activist, called the announcement “a step in the right direction,” but said he would prefer to see development of a safe drug supply.

“It’s not going to stop anybody dying of an overdose or drug poisoning,” Larsen said. “The drugs are still going to be contaminated.”

“I think we need stores where you can go in and find legal heroin, legal cocaine and legal ecstasy and things like that for adults,” he said. “The real solution to this problem is to treat it like alcohol and tobacco.”

Alissa Greer, an assistant professor at Simon Fraser University who has a doctorate in public health, said a regulated decriminalization of drugs could help lessen overdose deaths.

She said it would be good for users to be able to obtain drugs from "a regulated supply through various models, whether that’s a prescription model, a pharmacy model, more of a compassion club model ... rather than going down to 7-Eleven and buying heroin.”

British Columbia is the first Canadian province to apply for an exemption from Canada’s drug laws.

In 2001, Portugal became the first country in the world to decriminalize the consumption of all drugs. People caught with less than a 10-day supply of any drug are usually sent to a local commission, consisting of a doctor, lawyer and social worker, where they learn about treatment and available medical services.

In 2020, Oregon voted to become the first U.S. state to decriminalize hard drugs. Under the change, possession of controlled substances is a newly created Class E “violation,” instead of a felony or misdemeanor. It carries a maximum $100 fine, which can be waived if the person calls a hotline for a health assessment. The call can lead to addiction counseling and other services.

Carolyn Bennett, federal minister of mental health and addictions, said the experiment in British Columbia could serve as a template for other jurisdictions in Canada.

“This time-limited exemption is the first of its kind in Canada,” she said. “Real-time adjustments will be made upon receiving analysis of any data that indicates a need to change.”

Since 2016, there have been over 9,400 deaths due to toxic illicit drugs in British Columbia, with a one-year record of 2,224 in 2021.

Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart said he gets emails every Monday on drug deaths, including nine last week and 12 the week before. He said one week it was his own family member.

“I felt like crying, and I still feel like crying. This is a big, big thing,” Stewart said.

The 2.5-gram limit set by federal officials for the experiment falls short of the 4.5 grams requested by British Columbia. The higher amount already had been called too low a threshold by some drug-user groups that have said the province didn't adequately consult them.

Sheila Malcolmson, British Columbia’s minister of mental health, said fear of being criminalized has led many people to hide their addiction and use drugs alone.

“Using alone can mean dying alone, particularly in this climate of tragically increased illicit drug toxicity,” Malcolmson said.

She said the coroner in British Columbia reports that between five and seven people die a day in the province from overdoses and that half of those happen in a private home, often when people are alone.

“Fear and shame keeps drug use a secret,” she said.