Women in prison prepare for release with LIFE entrepreneurship program

Through Mercy Corps Northwest, hundreds of women in prison are getting a better understanding of what life looks like after they're released.

The women don matching clothing and have smiles on their faces, anxious and excited about their futures. Enthusiastic claps echo through the cafeteria as each name is called.

It’s graduation day, but there’s no cap or gown in sight. Instead, each woman wears a standard-issue blue crew neck, a pair of loose-fitting jeans and a generic pair of sneakers.

Some even use a little extra eye shadow they bought at the commissary to mark the momentous occasion.

They hope against all hope the past 32 weeks were enough to keep them out of prison for good.

Meet Vanessa, Myriah and Amy Chapter 1

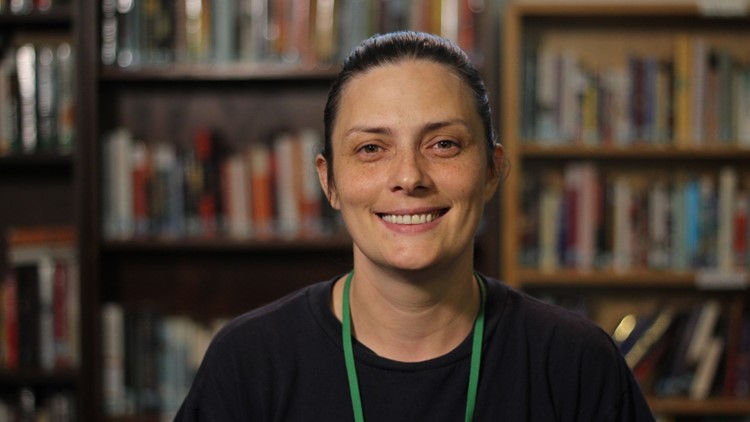

Vanessa Sherrod

Vanessa Sherrod, 39, was born in Guam and has lived for most of her life in Salem, many of those years alongside her husband and three kids. Her youngest daughter got cancer when she was just 4 years old, and after a couple of surgeries of her own, Vanessa quickly developed an addiction to Oxycodone.

“I didn't have them, I felt like I would die,” Sherrod said. “That was exactly what it would feel like. So when it came to stealing or making decisions to commit crimes, it was a given. I couldn't die.”

During the spring of 2015, she was writing up rental contracts as a landlord in Marion County, but upon receiving deposits, she would disappear. There would be no home for those renters to move into, and Vanessa would keep the money for herself. According to court documents, she did this to several different prospective renters.

A few months later, she began stealing merchandise from Lowe’s and returning it for cash.

“When it came to stealing or making decisions to commit crimes, it was a given. Every day to keep going, my role in my life was to meet my addiction," she said. "Everything else fell through.”

In an interview with KGW, Vanessa was brutally honest about the addiction’s toll on her behavior as a mother.

“I was numb to my whole situation during my daughter’s treatment. It’s no excuse for where my life fell into," she said. "I couldn’t make a logical decision because I was under the influence.”

Vanessa was convicted in 2016 on multiple theft counts and is serving a 62-month sentence at Coffee Creek Correctional Facility.

She often thinks about what life after prison will entail, but the guilt of paying back her victims a court-ordered restitution looms heavy.

“I wish more than anything I could have been paying them back this whole time instead of sitting here and just waiting for that chance to make it right,” she said. “They dealt with my demise … [the drugs] I was taking daily could have killed me any day.”

Myriah Williams

Myriah Williams, 27, was sentenced to 70 months in prison on arson and assault charges. She was out with friends at a Portland bar in 2015 when they met another group of people and went to their apartment for a house party.

An argument quickly led to a physical fight, and Myriah and her friends left. Police say Myriah and her friends returned to that same apartment in the early morning hours and set fire to it. Six people, including two kids, were asleep inside. Two people were injured with second- and third-degree burns.

Myriah grew up in Alaska and spent time in Oregon and Washington. She said after the fire, she briefly fled to Snohomish, Washington while her mother worried for her well-being.

“I felt really guilty for not seeing her before I turned myself in,” Myriah said. “I knew that was something I needed to do. I didn’t want to face her because I had already put her through so much.”

Myriah was in her mid-20s when she entered Coffee Creek, and it has significantly altered her worldview.

“Seventy months is a long time for someone my age. That’s a big chunk of my life,” she said. “Considering I wasn’t going around committing crimes prior to this, it was a life-changing incident for me.”

Amy Lorenzo

Amy Lorenzo, a mother of three, is serving a 66-month sentence on forgery charges. She was convicted of cashing fraudulent payroll checks and says, much like Vanessa, her drug addiction led to her crimes.

She was on the verge of divorce with her husband, who at the time started using meth. Eventually his addiction spread to Amy, who admitted all she wanted to do was to get high.

“I did anything and everything to support that,” Amy said. “Whether it was stealing a car or cashing a check, I did whatever I could to feed my addiction.”

Now a mother of two teenagers and one toddler, Amy desperately just wants to be a mom again.

“I used to think that I had to take them to Disneyland to show them I love them,” Amy said. “Now I just want to hold them and watch a movie with them. That would be the best day.”

What problems do they face? Chapter 2

Vanessa, Myriah and Amy are just three of more than 1,000 women incarcerated at the Coffee Creek Correctional Facility. It’s the only women’s prison in the state of Oregon, located just outside Portland in Wilsonville.

As of August 2019, the prison housed about 500 medium-security inmates and 580 minimum-security inmates.

Despite some of the womens’ hopeful attitudes about life after release, they face massive barriers after release: getting a job, reconnecting with family, transportation and housing, just to name a few.

According to Mercy Corps Northwest, within three years of being released, about a quarter of women who served time at Coffee Creek will be convicted again.

Three-quarters of the women will remain unemployed a year after being released. According to Effie Bustamante, Prison and Reentry Services Program Manager at Mercy Corps Northwest, unemployment is the single greatest indicator of recidivism.

A quarter of Americans with past convictions remain unemployed a year after prison. And the job market is bleak.

According to a Prison Policy report released in 2018, the unemployment rate for incarcerated individuals is 27%. That's higher than the total U.S. unemployment rate at any point, including the Great Depression.

“To be honest, I’m really nervous about that,” Vanessa said. “I think about employment; I think about being the best I can be to my kids and to society. I face a lot of barriers when I leave, financial ones. Getting my driver’s license will be an extreme amount of money. How do I take my kids to classes and myself to work without that?”

Estimates indicate that imprisonment penalizes an individual’s wages by 40 %.

What is the LIFE program? Chapter 3

Mercy Corps Northwest started the Lifelong Education for Entrepreneurs program back in 2007 to help women like Vanessa, Myriah and Amy find purpose while navigating life post-prison release.

The program is competitive – of the approximately 80 women who apply for the program each term, only 25 are admitted.

The goal of the LIFE program is simple. At the end of the 32 weeks, each woman has created her own small business plan, considering real-life challenges and financial hurdles she could face as a budding entrepreneur.

The group meets each Wednesday morning for several hours in a classroom inside Coffee Creek Correctional Faculty. Each woman carries a heavy binder filled with weekly reading and homework assignments. Each binder is decorated by the owner with family photos, doodles and ornate drawings of their names.

But before they begin the day’s lesson, the group goes through emotional regulation, a centering meditation to help them feel more present in an environment that is anything but quiet.

“It’s like you live in a dorm with 150 women, even at night when someone is sleeping, it’s loud. It’s actually kind of grounding to be in class,” Amy said, reflecting on the practice.

Amy, Myriah and 22 other women close their eyes, as Vanessa reads the weekly meditation, which lasts about two to three minutes.

“Pay attention to how you’re feeling at this moment,” Vanessa said. “Imagine your body releasing with each exhale.”

Amy, whose short stature carries quite a punch, laughs as she admits she never saw herself meditating.

“The first time, I thought that was really dumb. You know, someone talking in monotone,” she said. “But you kind of get into it after doing it for a while. It helps you breathe, be in the moment and let go.”

The group often plays host to female business leaders from the community who provide career advice or marketing lessons during weekly lectures.

They walk away with valuable building blocks like a resume, cover letter and the skills to create a basic budget and savings plan.

Beyond its small business goals, the class serves as a de facto stabilizer for these women, many of whom can get lost in the everyday fray of being in prison. It’s easy to keep track of time when every day is the same.

Myriah said the LIFE class gave her a refreshing sense of normalcy after more than three years behind bars.

“It takes me out of where I’m at, and it’s a good reminder this place is temporary,” Myriah said. “I’m almost done. And when I am done, I can go back to school, be in classroom settings and not be alienated because I was absent for five years.”

Vanessa’s small business idea was to create a nonprofit advocacy program for the justice-involved.

Myriah wanted to create a camp for kids to experience nature and live off the land, much like she did while growing up in Alaska.

Amy learned how to crochet through another program in Coffee Creek and wants to own a small business creating blankets for newborns.

As detailed as their transition plans are for their businesses, the scary reality of walking out of prison and trying to rebuild a life from scratch is inescapable.

At the bare minimum, they’re leaving prison a little more prepared for the real world, with a resume, a cover letter and a detailed transition plan – tangible skills they wouldn’t have had without LIFE.

Amy admitted she’s anxious about being released. After all, she and hundreds of other women here have depended on the system’s strict scheduling for years.

“I think this class gave me an opportunity of what it’ll first look like when I get out,” Amy said. “Thinking down to if I’ll need medication the first 30 days I’m out, a cell phone, exercise ... just being able to make a plan and sticking with it.”

Above all else, women who come into prison with very little and confidence can come out of the LIFE program an elevated sense of self-worth, according to Bustamante.

“It’s hard for them to shift their minds from, ‘I’m a person who’s at the whim of the experience I’m having,' versus, 'I’m a person who will take charge of my life in a legal way,'” Bustamante said. “The implications of the LIFE course are staggering. If we’re thinking of the social situations, ‘All of a sudden, I’m not just a felon, I’m someone with a skillset.’ You have a sense of ownership if you so choose. Knowledge is power.”

Success of program Chapter 4

The proof is in the pudding for LIFE graduates.

Less than 10% of the 300-plus graduates of the LIFE program have returned to prison, compared to 19% statewide and 42% nationally (according to a May 2018 report from the State of Oregon, reflecting recidivism rates of both female and male inmates).

9.7% of LIFE graduates have returned to prison, compared to 19% statewide and 42% nationally.

15.9% of LIFE graduates have been convicted for a new misdemeanor or felony, compared to 43% statewide and 67.8% nationally.

21.4% of LIFE graduates have been arrested for a new crime, compared to 57% statewide and 68% nationally.

Bustamante said 90% of LIFE graduates have found employment and/or continued their post-secondary education within 30 days of their release from prison.

One of those women is 28-year-old Sammantha Saucedo, who spent most of her time between the ages of 18 and 24 at Coffee Creek. She took the LIFE course, and she admits post-release life wasn’t easy.

“I was sleeping on my aunt’s couch for first few months,” Samantha said. “My first goal was housing, but I realized I need a job for that and finding a job was really hard. I remember crying on the couch thinking, Where am I gonna work? Who’s gonna hire me? I have no job skills.”

She fell back on her transition plan, the same one Vanessa, Myriah, Amy and their fellow classmates created.

“Mercy Corps and that transition plan were a lifeline. I still use it today for my goals,” she said. “You have to dig deep. What do you want to accomplish this day? This month? This year? Without it, I would have been so lost and discouraged without self-confidence.”