Meet the professionals helping Portland students with their post-pandemic mental health

After the disconnection of remote learning during the peak COVID-19 pandemic, students are adjusting to the new normal — but mental health gaps remain.

It's been a rough few years for students, teachers and parents. With leading pediatric health organizations and the U.S. Surgeon General highlighting an urgent need to address youth mental health in late 2021, it became clear that kids nationwide needed help.

Throughout the pandemic, KGW's Christine Pitawanich reported on a number of education-related stories, many of them focused on youth mental health. Mental health professionals broadly agree that there have been pre-existing issues with youth mental health that the pandemic made worse.

It's been more than a year since that Surgeon General advisory, and Pitawanich has been checking in with school counselors at Portland Public Schools to see how things are going now.

Portland Public Schools is the largest district in Oregon, home to roughly 42,000 students scattered across 81 schools. KGW followed three school counselors at Sitton Elementary in St. Johns, West Sylvan Middle School in the Southwest Hills and Lincoln High School downtown.

As students got back in the swing of fully in-person school, Sitton Elementary counselor Deb Blume said that staff have worked hard to make kids feel welcome and at-ease.

"We really focused on empathy and really understanding other people's feelings," Blume said.

The same is true at both the middle and high school levels.

"We've had to be so creative in order to reach kids," reflected Rebecca Cohen, counselor at West Sylvan. "We had to make it even more welcoming and more embracing to their needs."

"We're still righting the ship of students going back to normalcy," said Jason Breaker, counselor at Lincoln High School. "The more we're back in person, I've seen less mental health concerns."

Regardless, those mental health issues are still there. School counselors, who often work alongside teachers, said that they are having to teach kids how to interact with adults and one another.

Counselors are often the first line of defense in helping kids who are struggling. A counselor's scope of work is broad, covering everything from suicide to college applications. With hundreds of students under their care, the work is challenging but fulfilling.

"Mental health is everyone's business," Breaker said.

"We want to be foundational for students' academic and emotional health," said Blume.

"It's the best job in the entire world," said Cohen.

Counselors also told KGW that what's happening outside of school walls can affect students as well, seeping into the classroom. That doesn't just encompass home life, but the threat of gun violence and the prevalence of homelessness — things that pervade the atmosphere of the city they call home.

Some viewers expressed concern regarding the three schools profiled: one in North Portland and two others on the city's west side. For more context, KGW spoke with Marquita Guzman, who has worked as a high school counselor for 15 years. She has experience in schools across the district, including those on the east side.

Now, Guzman's role is to oversee and support the roughly 165 school counselors across the district. She said the vast majority of the district's highest needs schools are located on the east side of the city, but each school is different. Guzman said it's true that certain communities on the east side are disproportionately impacted by issues such as the pandemic and violence. Still, she said, students districtwide seem to be doing better than they were last year when they started coming back to the classroom in person, full time.

Guzman also said schools with students who have higher needs tend to have more mental health professionals in their buildings because that's where the funding goes.

For each school that KGW profiled, there are similar struggles and there are different ones. Here's what they're doing to help students succeed.

Sitton Elementary St. Johns

10-year-old Dibera and Uriel, along with 7-year-old Sita, have the inside perspective on what it's like at Sitton Elementary in North Portland. Sometimes the struggles are more simple, like which subject in school they find the most stressful. But dig a little deeper and elementary life can involve some hard stuff.

"I've been bullied," said Dibera.

It helped knowing that there was an adult nearby who she could talk to.

"I just felt more like safe and like better," she added.

One of those adults is Deb Blume, a school counselor of 14 years.

"As a school counselor, I teach in the classroom, so that differentiates me from a social worker or school psychologist," Blume said. "It's a new world nowadays."

Particularly since the pandemic, she's one counselor who's needed to teach kids how to interact with adults and one another in a healthy way.

Even kids in elementary school have anxiety, Blume said, and it's typical at this age. The difference is that she's seeing more of it after the isolation and stress of the pandemic.

"They're coming with concerns about friendships, managing big emotions, problem solving," Blume said.

Blume regularly sees students who are contemplating self-harm, but she's adamant that she won't shy away from the kids' big feelings and problems.

To help, staff at Sitton normalize talking about mental health. Blume and others at the school are trying to give students tools that they can use to deal with problems both in and outside of school.

"We have posters in our fourth and fifth grade bathrooms with the new suicide hotline that was created this past year," Blume said, referring to the nationwide 988 hotline. "I'm in the classrooms every week teaching social skills and teaching mindfulness."

It's thanks to that kind of attention that little Sita now knows how to handle conflict on the playground, through a concept called "A Bug and a Wish."

"If someone keeps like mimicking you in something, you could like say, 'It bugs me when you mimic me and I wish you would be nicer,'" Sita said.

Meanwhile, Uriel is grateful for the grief group at the school. He had someone close to him pass away.

"It feels good expressing what you've been through ... and the day from when I let it go out and I felt just better," he said.

This year, new sensory walls were installed in the hallways. As kids pass, they can run their hands through the interesting textures or jump on bubble pads on the ground.

"It's a place for them to take a break or engage in a way that gives them a sense of calm," Blume said.

The school spent $30,000 on its kindergarten classrooms last fall so that students could start every day with play. That simple activity — play — was a big part of what kids missed out on during remote learning, and it's important for brain development and mental health.

"In our school last year, one year post-pandemic, as the state test scores in reading and math really plummeted ... our school in particular, we grew 8% in literacy overall and 15% in math. And I think that is in direct relation to the mental health supports that we've had in our building," said Becky Berry, principal at Sitton.

While much is being done with mental health staff at Sitton coming together monthly to learn and share practices, more help is always needed.

"The American School Counseling Association recommends a 250-to-one ratio for counselors to students, and at our school we're really lucky because we're about as close to that as a schools get in the metro area, at 340 students to one school counselor," Blume said. "As a mental health advocate, we can do all this work here, but some kids need more than schools can offer."

In the tri-county area, Blume said that there simply aren't enough resources for kids outside of school when they need extra help. The tough part is that when kids don't get the help they need outside of the classroom, those issues find their way back to school.

West Sylvan Middle School Southwest Portland

Students in middle school are always in a tough spot — stuck between being a kid and transitioning into a teenager. While all PPS students were significantly impacted by the pandemic, PPS Student Success & Health program administrator Marquita Guzman said that students transitioning to middle school were hit especially hard since that was already a difficult time for students prior to the pandemic.

"We all have some personal stuff in our lives at home that most teachers don't even know about," said Nolawi Aklilu.

"We are trying to find who we are. Sometimes we change in a way that doesn't work for people around us," said Avery Baz.

"It's hard to balance like sports, school and like outside life with your family," said Miles Raff.

These kids at West Sylvan Middle School said that there just doesn't seem to be enough time in the day for everything on their plate. All of them are 13 years old, currently in the 8th grade.

"There's just so much going on. You can't get your work done. You're mad that you didn't get enough sleep," said Tolba.

It's school counselor Rebecca Cohen's job to help the students here. She was named Oregon School Counselor of the Year for 2022. And with therapy dog Norma in tow, she walks the halls every day, greeting kids or taking on lunch duty.

"I see kids having a harder time focusing," Cohen said. "I've also seen quite a few kids that are feeling suicidal and have had more kids in poverty than we've had in a long time, especially at this school — houselessness, needing more support in a variety of ways."

During passing time, Norma gets lots of love. Kids will even take her for walks. Her presence is very intentional, helping students with their mental health just by being available for pets and hanging out.

"Sometimes kids like dogs better than people," Cohen said. "Part of being great educators is teaching kids to manage their stress, so that's a huge part of my job."

Recently West Sylvan was in the news when a 13-year-old Black student was assaulted. Two students threw him to the ground, tied his hands behind his back and kneeled on him to re-enact the murder of George Floyd. The student's father was justifiably horrified.

"I was flabbergasted, I was outraged, I was angry," he told KGW. "I couldn't even believe what I was hearing."

Raheem Alexzander went public with the story when he felt that the school and PPS didn't do all they could to address the seriousness of what happened.

KGW has been covering classrooms in crisis since 2019, diving into the outbursts that sometimes culminate in physical or violent behavior in schools. Anecdotally, teachers reported that those disturbances reached another level last year when students returned to the classroom after pandemic remote learning.

But the district's data, at least, doesn't quite bear that out.

During the 2018-2019 school year, the district recorded 4,162 major discipline incidents involving 2,193 students. Numbers were lower during the 2021-2022 school year, with 3,101 incidents involving 1,691 students.

The data doesn't tell us whether the nature of these incidents may have changed — perhaps becoming more severe — but the rate of reported incidents unequivocally fell. Some educators have their own theories about why that happened, and it wasn't because of a drop in behavioral issues.

Regardless, the anecdotal evidence suggests this year is different, even if it's too early to have data for comparison. Despite the headline-making incident at West Sylvan, teachers and counselors report that it's been overall calmer compared to last year. Still, there's a big effort to better connect with the students.

"We've had to be so creative in order to reach kids," Cohen said.

There are more than 40 clubs at West Sylvan, Cohen said, and about half are new. Many are groups that she and her team have created so students can feel more connected to the school and with each other.

"I have an equity group that I run, I do a Hopes and Dreams Club, I'm involved in the Gender-Sexuality Alliance," Cohen said. "Everything, I'm telling you, is something I've created with my team since the pandemic because we wanted, we realized kids more than anything need community."

Also this year, Cohen said that students have 30 minutes carved out every day, dedicated to helping them develop interpersonal and academic skills.

"We do things like teaching communication skills, how to talk to your teacher how to talk to each other when you have conflict," she said.

"I think it's important we do have those times when we all talk about how we feel and let those emotions out," agreed Macy Bethel, another West Sylvan 8th grader.

Cohen and her team are doing everything in their power to positively impact the roughly 700 students who attend West Sylvan.

"Counselors are first line of defense," she said. "It's the best job ever. It's a big job. We have a lot to do but it's very joyful for me."

Marquita Guzman said that in the last two years, PPS has recognized that middle school is a crucial time for kids, one that is key to building confidence. As a result, more resources have been given to middle schools — and now middle school counselors have the lowest ratio of counselors to kids among other levels.

Lincoln High School Downtown Portland

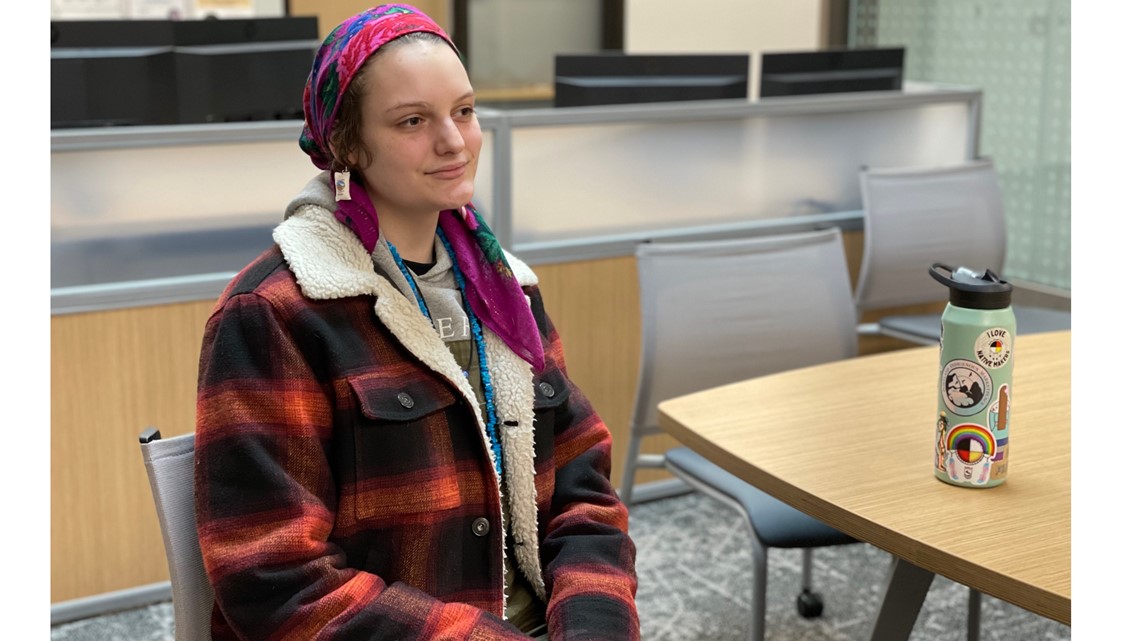

The last few years have been rough on so many people, including 18-year-old Bodie Suncloud.

"The amount of depression and anxiety that has kind of formed in our community because of COVID," Suncloud said. "I developed an agoraphobia because of the whole issue and it was very difficult coming back to school."

Agoraphobia is an extreme fear of crowded places. Suncloud isn't alone in feeling the anxiety and stress associated with coming back to school after the height of the pandemic.

"I'm still seeing a large number of students with anxiety or depression," said Jason Breaker, "and I would say this underlying grief because a lot of people have lost people in the pandemic and there's been a lot of economic hardship for families."

Breaker is a school counselor at Lincoln High School. At this academic level, he ends up doing a lot of paperwork — from college applications to letters of recommendation and reviewing transcripts. Regardless, he and his canine co-counselor are also busy spending time with students, trying to foster connection.

"There's a social connectedness of students who may not have even known each other before but with the dog at the center, students connect," he said.

Breaker said that last school year in particular was rough.

"Last year I saw probably more severe mental health concerns, students in crisis, than probably all of my years combined," he said.

According to Breaker, staff at Lincoln conducted over 30 suicide screenings last school year. He said that's higher than normal. But this year, things are different.

"Our trajectory is below that this year if I'm just using suicide risk assessments as one statistic," he said. "We're kind of righting the ship of students going back to a normalcy, at least that's what I keep telling myself."

Still, students are dealing with a lot. They're juggling class work, teen life and the environment outside school walls.

"There are lots of homeless people like just down the street," said Suncloud.

Not only does it break her heart to see people in need, but Suncloud said that the tents, trash, urine and feces mean that she has to change up her route to and from school. Then there's the gun violence reported outside of a few Portland high schools this year, with several shootings leaving students injured.

Breaker said he knows that school can be stressful, which is why staff try to do things to promote wellness.

"We have a wellness fair where we have over 50 different sessions where students will have a block of time to be able to interact with everything from baby goats to affinity groups," he said.

Lincoln also has a partnership with a community mental health provider, Breaker said, which may help students get seen by professionals earlier than they would otherwise.

"The amount of support in the school is amazing, even though it does need to be worked on," Suncloud acknowledged. She added that she hopes teachers get more training to deal with students who might be in a nonverbal state, having panic attacks or meltdowns.

While Breaker said that things are better now than they were when students had just returned to the classroom last year, the prevalence of mental health issues is still greater than it was before the pandemic. Still, students at Lincoln High School have a passion for social justice, and many work to channel their anxiety into leadership and advocating for change.

'There's never enough of us'

To a certain extent, the youth mental health crisis that was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic can be traced by the number of suicide screenings each year, though the numbers were clearly impacted by the nature of pandemic response.

During the 2020-21 school year — during which students were largely away from the classroom and learning remotely — PPS reported a total of 198 suicide screenings. During the 2021-22 school year, that number leaped to 754 suicide screenings.

As of Feb. 1, PPS has recorded 361 suicide screenings. While it's too early to say for certain, that could mean that screenings will have fallen compared to last school year.

KGW is still waiting on suicide screening numbers from the 2018-19 school year for a more accurate comparison to a "normal" year.

The counselors and administrators that we interviewed for this story all had similar things to say about the outlook for their kids. While circumstances have certainly improved over last year, there are still immense challenges.

"I mean, there's never enough of us," said Rebecca Cohen of West Sylvan Middle School. "We are very fortunate to have a mental health provider who comes in once a week who does therapy with kids, but we don't have a social worker so that means our counseling staff does all the social work."

"I think we're struggling as a community here in Portland, in our tri-county area. We're struggling as a state and we're struggling as a nation to provide care, especially for children who are struggling with their mental health," said Deb Blume of Sitton Elementary School.

"That would be my wish for the future, is getting students the supports they need fully in school and outside of school," said Jason Breaker of Lincoln High School.