PORTLAND, Ore. — Eighty-one schools in the Portland area could close down Nov. 1, leaving 45,000 kids out of classrooms, if Portland Public Schools and the teachers union don't reach a deal in the handful of days remaining for negotiations. Based on the last offers from both sides, they remain about $60 million apart when it comes to total salaries.

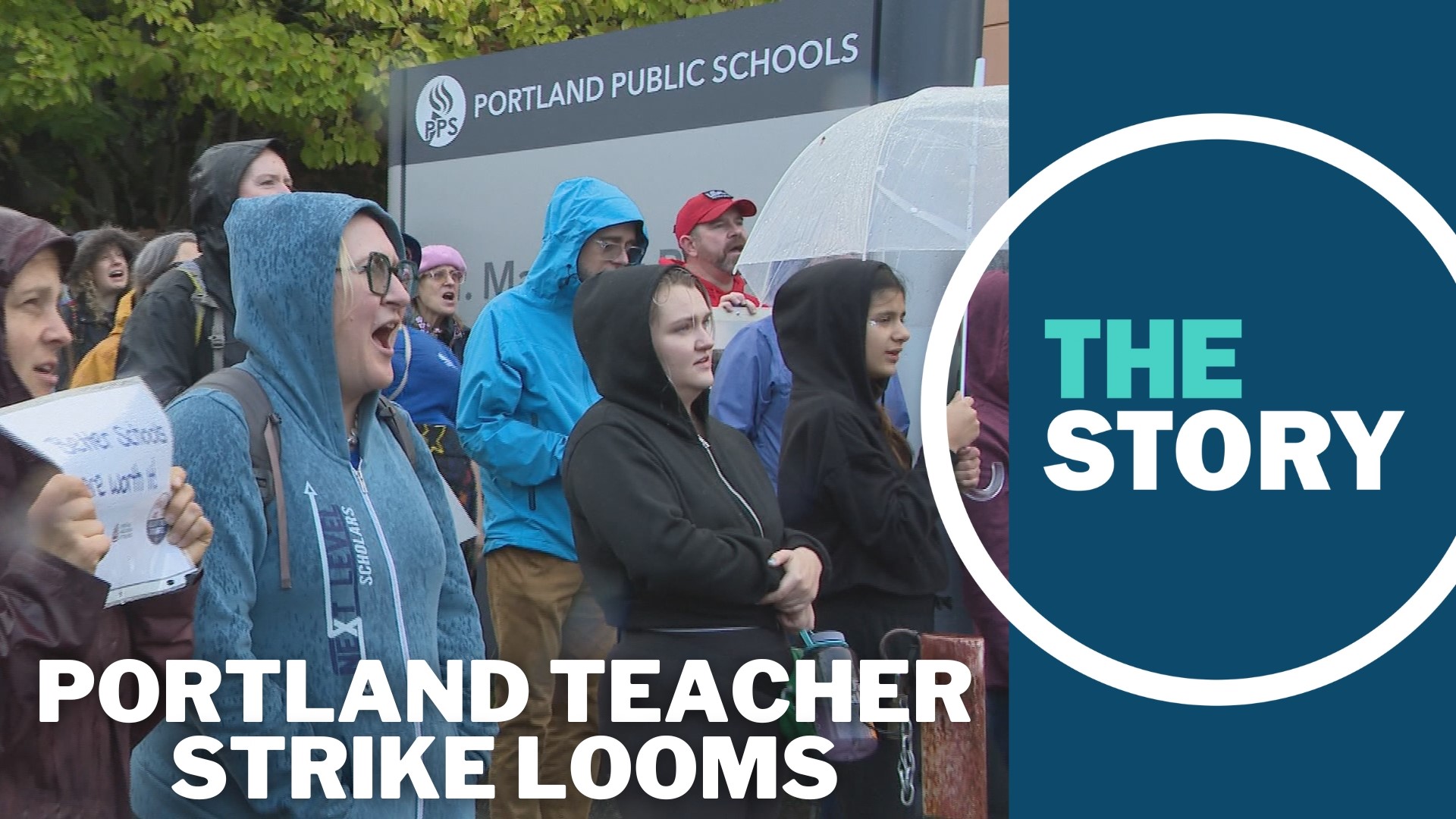

About 4,000 teachers affiliated with the Portland Association of Teachers are prepared to leave classrooms and hit the picket line beginning next Wednesday, Nov. 1, if their demands for a new three-year contract aren't met.

The union and the district have been in talks since teachers' last contract expired in June. Negotiations have gone on for month, and they've been in marathon mediation sessions this week as they attempt to reach an eleventh-hour deal.

Portland Public Schools strike FAQs for parents: What's open, what's not

If the teachers do go on strike, it will be the first time in the history of Portland Public Schools. And strikes have been in the air — several nearby districts in southwest Washington went on strike at the beginning of the school year, though they proved relatively brief.

But it's possible that more separates PPS and the PAT at this stage than in those other recent examples. The union wants to increase salaries for teachers by 8.5% this year, 7% next year and 6% for the third year. The district has offered to go about halfway there: 4.5% this year, 3% next year and 3% again in the final year.

The teachers are also asking for more planning time in their weeks so that they can work on lesson plans, grading, communicating with parents and completing other tasks that they can't do while teaching students.

Right now, PPS elementary school teachers get 320 minutes of planning time each week — or a little over an hour a day. Middle and high school teachers get one class period each day for planning.

The union wants planning time increased to 440 minutes a week, or just under an hour and a half each day, for all teachers at all grade levels.

The district has said that they're willing to give elementary school teachers 400 minutes a week for planning, but they're not giving any more time to middle and high school teachers. Officials said that they fear more planning time will result in students losing too much instructional time.

'We can't do it under these conditions'

Another major sticking point is class sizes. Teachers want new limits, including a cap of 23 kindergartners per class, 25 first graders and 26 for all other elementary school grades. For middle and high schools, they instead want a cap on the total number of students taught per day: 150 students for middle school teachers and 160 for high school. There are other limits proposed by the union regarding things like special education.

But the district has said that class caps simply aren't feasible. They claim that it would require adding an extra classroom if one group is over the limit, and some schools simply don't have the space. PPS also argues that they would be forced to hire 500 teachers to create smaller class sizes, costing them $200 million.

Right now, PPS pays teachers extra if their classes go over a certain number of students. They want to keep that policy in place.

Then there are classroom conditions. The teachers want to be able to refuse to work in a classroom if it isn't in good condition. That means things like temperature; they don't want to be in a classroom that's below 60 degrees or above 90 degrees, instead having school administrators move them to a space that's temperature-controlled until the classroom is properly regulated.

That's been an issue for Portland school in recent years. Many of the older school buildings lack air conditioning, and summers have produced record temperatures — sometimes not just during the summer break.

Teachers also want to be able to refuse to work if there's a water leak of some sort in the classroom, or if the power is out. And they want their classrooms to meet what they are calling "basic cleanliness standards," meaning they don't want to be teaching kids around rodent droppings, mold or other issues with the facilities.

"We want to do right by everybody, but we can't do it under these conditions," PAT President Angela Bonilla, told KGW. "We can't do it in moldy classrooms, and classrooms with mice, rodent droppings everywhere, we can't do this in buildings where the roof is leaking — we need so many more things to make our district functional and to make sure that we're supporting our kids, and that is why we won't be in school."

PPS said that they're working on getting the buildings fixed up, but that many of them are just aging — several of them are turning 100 this year — and the money to fix them up is slow in coming. They also said that fixing up the buildings is a logistical challenge, since they have to find a new space for the kids to learn while parts of the school are under repairs.

The district also takes issue with the term "basic cleanliness standards," which they claim is too subjective. Everyone has a different idea of basic cleanliness, the argument goes. But as far as things like rat droppings, PPS said it's not very common — they've had fewer than 10 reports this year.

The last big point of contention is student discipline. The district has procedures in place to discipline kids who break the rules, as well as different ways to address the behavior based on what the student does. Both the union and the district agree that they should take into consideration everything that's going on with a child — whether it's bullying, racism, homophobia or transphobia, issues of poverty, abuse or other things going on at home — and they both want to see the district move away from flat-out removing a student from school if they're having behavioral problems.

But the union in particular wants each school to have a designated intervention space for kids to go when they're having a hard time in the classroom and they're getting disruptive or acting out. They want that space to be equipped for the student to keep learning, and they want it to be staffed all day long by someone who can help the students with their work.

PPS said that they like the idea, but they can't get there yet. They've agreed to start looking into spaces that can be used in the schools, but at this point, they said they don't have that space at all schools — and they certainly don't have the money to hire a staff member to work in it all day.

Is it raining?

There's a lot more to the contract negotiations and each side's proposals. The contracts are long and dense and contain caveats for a wide variety of scenarios. But these points of contention remain some of the biggest pieces that PPS and the PAT cannot seem to agree upon.

To boil it down: Teachers say the district has the money to meet all of their demands: they just don't want to spend it. They say the district is keeping too much money in its rainy-day fund, which is currently about $100 million, that they're spending too much on administration at their central office and they're not spending enough on schools.

"Year after year, the district projects a deficit, and year after year, they have an increased ending fund balance," said Bonilla. "So they say there's no money, and then at the end of the budget year, there's always money left over — and not just in the general fund, but in the special funds, the funds that we fought for to get students more supports."

The district's representatives say they want to be able to give the teachers everything they're asking for, but they have to be responsible with the money they have. They've agreed to spending some of the rainy-day fund, but they say public education isn't getting enough support from the state — that they shouldn't be on their own in coming up with the necessary funds.

"We would like to give our teachers the world," said Renard Adams, chief of research, assessment and accountability at PPS. "But we live within a fixed resource allocation that comes from the state, and what we're talking about is a fundamental underfunding of the quality education model ... We think our offer is fair given the constraints of our resources."

The district's proposal, Adams said, would have average teacher salaries reaching $87,000. By the end of the contract, 60% of teachers would make $90,000 and 40% would make $100,000 or more, he added.

This past spring, the Oregon Legislature invested a significant amount in public schools, setting aside $10.2 billion for the state school fund — $700 million above what they spent the two years prior and the most they've ever spent on the school fund. Lawmakers said that when paired with local property taxes, the total fund for K-12 schools would reach $15.3 billion, a 12% increase over the last two years.

On top of that, state funding is pumping another billion dollars per year for early learning and K-12 education through the Student Success Act, which passed in 2019.