PORTLAND, Ore. — Jenn Coon knows what it’s like to lose nearly everything. Her job. Her marriage. Her 8-year-old son and 12-year-old daughter. Her connection with reality.

“It was a very dark time in my life,” Coon says. “I just dug myself a hole and I could not get out of it.”

It began with prescription painkillers, first legal, then illegal.

“Before I knew it, I was taking six pills every three hours,” Coon remembers. “I would fly out of town on business and have to take 200 pills with me.”

Vicodin turned to heroin, then to meth. She received two DUII’s and lost her license.

And before Coon knew it, she was living on the street.

“I slept outside a lot,” Coon said. “I remember waking up frozen to the ground.”

Coon said she tries not to remember most of those two, no three, no it was actually four years — some of that time pushing a shopping cart along Southeast McLoughlin in the Oak Grove area.

“I think by nature, we minimize it,” she told KGW's David Molko. “But honestly, it was four years.”

And then, amidst the drug-induced paranoia, the loneliness and the fear, Coon arrived at what she calls her rock bottom, an encounter in a supermarket.

“I was filthy dirty and had abscesses on my arms … and I was probably stealing something to eat,” she recalled. “And I saw my daughter. I hadn’t seen her for a couple of years. And she saw me. And all I could do was run out of the store. And she was wanting me to run to her.”

Soon after, Coon pushed that shopping cart with everything she owned to a detox and treatment center, and waited outside for a week or two until they took her in.

She’s been clean ever since.

Offering hope, one person at a time

Now, nearly six years into recovery, Coon has turned her own struggles into her life’s work.

KGW shadowed Coon on the street outside Old Town’s Blanchet House, the Portland nonprofit that offers three meals a day, six days a week to anyone in need; plus clothing, and for those who are ready and willing, residency programs that provide a path forward.

Coon has been with Blanchet House full-time for year. Before that, she worked here for a year as a contractor.

Her official job title is “Peer Support and Housing Specialist,” though Coon puts it like this:

“I love that I’m able to offer hope.”

And hope, she said, is what’s in demand among those who have nowhere to call home, others who suffer from substance abuse and still others struggling with their own connection to reality.

Often, Coon said, they are one and the same.

As the line for lunch started forming on the sidewalk outside Blanchet House on a characteristically fickle early spring day in Portland, Coon instantly saw some familiar faces.

With a smile on her face, she approached a man she worked to get into shelter, who later didn’t show up. But instead of showing frustration, she responded with humor and without judgment:

“You’re silly,” Coon chided him.

“I know,” he admitted.

“They have a bed there waiting for you!” Coon said.

She offered to find someone else a new coat.

“I’ll go down in a little while, okay hon? Probably an extra-large with a hood, okay?” she said.

And she promised to make a call to Bybee Lakes Hope Center for another guest who approached her for a connection to detox — handing him some bus tickets and asking him to return later than afternoon.

“He may or may not show up,” Coon said later. “I won’t work harder than they work. And I learned that the hard way.”

Friendly but firm

Lunch began in Blanchet’s communal indoor café and the line outside started to shrink as guests were welcomed inside.

We met Leonard, an elderly man who lives in a tiny apartment infested with bed bugs. Even though his place is across town, he comes for meals at Blanchet House every day, wheeling his walker up from the transit stop.

A man carrying a bright red gas can slipped inside the café, then returned moments later to hide the can on the sidewalk behind the open door.

Up to this point, lunch had been a fairly calm, orderly process. But then we saw a woman approaching who appeared to be in crisis, sobbing and approaching the entrance at a frenetic pace.

Coon seemed to know exactly what to do.

“Hi honey, you’re okay,” Coon said with warmth in her voice, as the agitated woman rushed past in a blur.

“Can you call (Portland) Street Response for me?” the woman asked, then shouted as she rushed inside. “They won’t leave me alone!”

Coon followed her inside the café, continuing her efforts to calm the woman, then returned to call 911. Dispatch connected her to PSR.

“She’s been coming here as long as I’ve been here,” Coon said. “And that was fairly calm for her.”

Sometimes it’s out-of-control yelling, she said, but agitation is the norm for this particular guest.

Other guests have assaulted staff members, Coon said. One time, someone threw a piano bench through the window.

And then there was the time a man pulled a knife on her, Coon said, and backed her into a corner.

In that case, she recalled, her trademark friendliness quickly turned firm. She ended up pressing charges, and the man went to jail where he eventually got the treatment she said he needed.

Addiction is certainly an issue here on the streets of Old Town, like for the man who approached her looking for detox. But it's far from the only problem.

“I used to think a lot of it was drugs until I worked here,” Coon said. “Honestly, a lot more is mental health. A lot more mental health than I thought.”

And whether the behavior she encounters is caused by substance use, schizophrenia, Tourette's syndrome or anxiety, among any number of other possibilities, Coon tries to de-escalate where she can and call for help where she can’t. Most of all, she said, she tries not to judge.

She remembers her own meth-fueled psychotic episodes, which she describes as “hearing voices” and “thinking that people are after you that really aren’t.”

RELATED: At the intersection of homelessness, mental illness and addiction in Portland lies psychosis

She acutely remembers the feelings of fear and loneliness, and of not knowing who to turn to or where to go.

“We need more (behavioral health) treatment,” she points out. “We do.”

Those experiences now guide how she approaches others.

“I don’t ever say I can’t help anyone,” Coon said. “Even if I have to call 911, I feel like I’m helping someone. The only time I won’t help someone is if they refuse help.”

And, Coon added, it’s important to keep in perspective those encounters that involve threats or violence are the exception.

“There’s a lot more good than there is bad,” she said.

Credibility and connection from lived experience

As lunch wrapped up, there was a small commotion in another Blanchet House doorway around the corner.

Coon met a man named Christopher, sitting against the building, who appeared to have cuts and abscesses on his hands and arms.

She quickly grabbed a baggie with band-aids and ointment, and then a stack of blankets for good measure.

“I don’t have any big blankets,” she told him. “But I brought you three of these little blankets. And I’ll get you a coat also.”

Christopher was clearly grateful. So are countless other lunch guests and clients whom Coon has helped over the past two years, in both big ways and small.

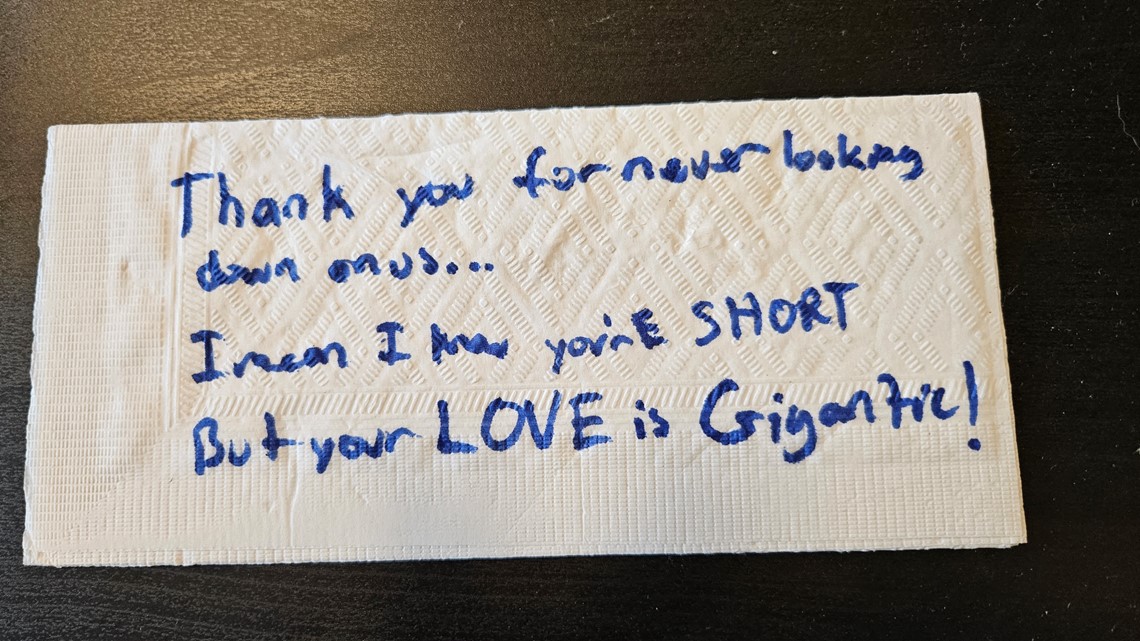

One of them once left her a note on a napkin:

“Thank you for never looking down on us,” it read. “I mean, I know you’re short, but your love is gigantic.”

Coon jokes that her height, under five feet, may make her seem more approachable.

But really, she said, her credibility comes from her lived experience.

“You can’t learn it in a classroom, you can’t read it in a book,” she says. “I’ve been there, I’ve done that — literally. I’ve shot up heroin and I’ve eaten out of a garbage can.”

And while Coon said she finds reward in the small daily victories, like when someone returns with “tears in their eyes” to give her a hug for getting them into detox, that’s only part of what keeps her going, day after day.

She does this work, she said, as a daily reminder to herself — a reminder of her journey out of the “dark days” to a job she’s proud of, and an apartment that’s comfortable and stable.

And it's a reminder to never take for granted that her children, who’ve since grown into young adults — 23-year-old Nathan and 27-year-old Madison — are back in her life.

“I do it because it keeps me sober,” Coon said, then nodded. “And that feels good. It just feels good.”