PORTLAND, Ore. — Every 10 years, a group of 20 community leaders is selected by the Portland City Council to spend two years reviewing the city of Portland's charter. This includes reviewing Portland's form of government, a commission-style format that no other major city in the U.S. uses.

Portland's city government is made up of the mayor and four elected commissioners. Unlike city council-style governments, the mayor and commissioners are elected citywide, not by localized geographical districts.

A second major difference is how much power Portland's city commissioners have. In Portland, the mayor assigns each commissioner bureaus to lead. For example, the mayor is also the police commissioner, Commissioner Dan Ryan heads up the Housing Bureau and Commissioner Mingus Mapps is in charge of the Water Bureau.

Back in the 1920s, when Portland had about 250,000 residents, the commission-style form of government was a progressive idea. It was a way to give the voters some real control over the bureaus that kept the city running.

But in 2021, in a city of nearly 700,000 people, many point out that it seems silly and ineffective to give one person so much work to do. The City Club of Portland has done extensive studies and research on reviewing the charter, and released reports in 2019 and 2020 about how ineffective the current form of government really is.

"Two of main things that we keep hearing over and over are accountability and transparency," said Vadim Mozyrsky, one of the charter commissioners. "There's certainly a feeling that at-large election system might not be representative of Portland as a whole, whether you choose east versus west Portland or the various communities within Portland. Also, is our form of government responsive to the residents of Portland?"

He said the commission is exploring different of voting, from district voting to at-large voting, even ranked-choice voting.

Mark Stephan, an associate professor of political science at Washington State University Vancouver, is on City Club's Board of Governors and sits on two research committees.

It's unknown what the city's new form of government could become, but City Club of Portland has suggested appointing a nonpartisan city manager and doubling the number of city commissioners based off geographical districts.

"The overall perspective [of the studies] was that if we could switch our form of government, it would be more effective. It would lead to a more cohesive city council working towards the benefit of the whole city, and it would better represent the interests of the whole city," Stephan said.

He said it would take time and money for people to understand how a new system of government would work, but it would pay off in the long run.

"There would be a couple of years of having to learn this new system, but a lot of other governments have done this across the country," he said. "They have made arguably bigger changes. It's not easy, but it's definitely doable, and I think in the city of Portland, it's very doable."

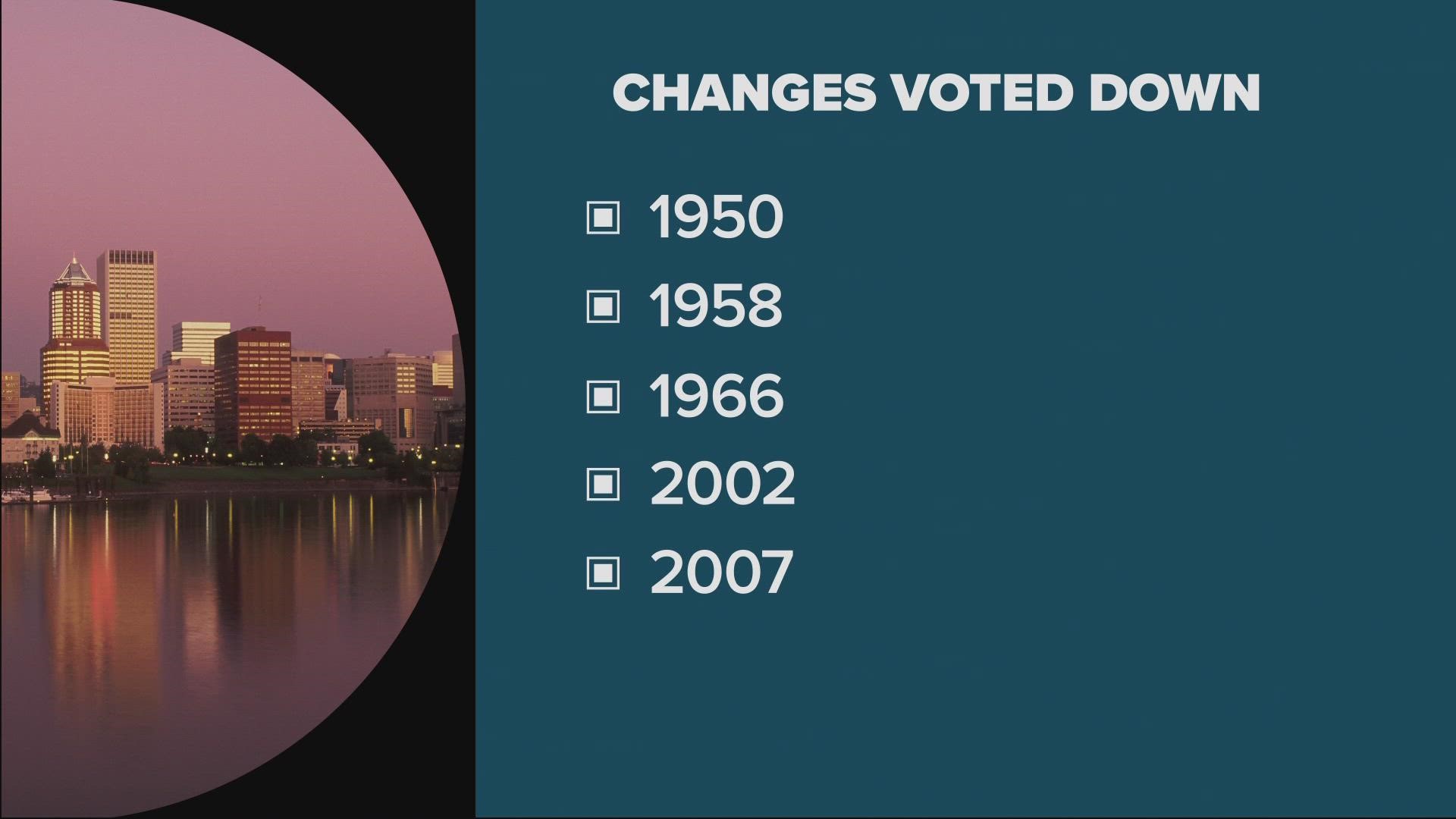

Portland voters have an extensive history of voting against changing their government. Voters have shot down attempts five times since 1950.

There are a lot of theories on why Portland voters turned down these changes. Some people think that voters just don't understand the process, while some others think Portlanders are stubborn — and like being an outlier on a national scale with our archaic form of government.

Stephan, however, thinks this time around could be different.

"I think reforms are on the horizon. I think there's a strong enough feeling," he said. "There's an attempt by the charter review commission itself, and also a lot of other civic groups, to really increase citizen engagement on this topic at these earlier moments, not just waiting until there's a referendum later on. And there's a sense that we want to make some changes and it's going to make things better. There's a commitment that I think makes this moment much more likely to be a moment of change than we've seen before."

Another charter commissioner, Salome Chimuku, agrees.

"There's a lot of people coming to some of our meetings, especially our informational ones, to learn more about how the city functions," she said. "We had different bureau directors come in and give reports and talk to us about their efforts. We had all the equity officers come in and talk to us about what they would like to see happen. We had other trainings open to the public that people attended and participated with us in as well. It's great because people do come with ideas. I like to think that people also hear something new and then it makes them go out and hunt for more information and learn something new about something they maybe didn't know much about."

Change is possible, proven by one of Portland's suburban neighbors. In May 2020, Beaverton voters approved a change to their city charter, which created a position for a full-time city manager to oversee the city's day-to-day operations and expanded the size of their city council from five to seven members.

"I think it has been an adjustment for Beaverton ... on some level, some costs go into this, but it's about adjusting to a new way of interacting for the council and the mayor and the city manager. It's not necessarily like you snap a finger and it's changed overnight. It's going to take some time, no matter where it happens," Stephan said.