PORTLAND, Ore. — Portland Fire & Rescue responds to more medical calls than it does fires, and has been dealing with an increasing number of non-emergency calls in recent years. But a newly released city audit found that the city's Fire Bureau has done little to help its dedicated community health response teams grow and shoulder that burden.

Moreover, the Portland Auditor's office identified a lack of clarity in the Fire Bureau as to whether these programs are expected to alleviate the burden on firefighters at all.

Over the past three years, the Portland Fire Bureau has responded to some 86,000 incidents, 63% of them medical calls, the auditor's report states. While many of these medical calls were emergencies that required a full response, many others represented low-acuity and non-emergency complaints — and the share of non-emergency calls for service has been growing in recent years.

In fiscal year 2020-2021, almost one in every three calls for service were non-emergency calls. Getting a full fire crew to those scenes is often time-consuming, expensive and takes crews away from potential emergencies.

According to PF&R's own accounting, firefighters responded to some 7,000 drug overdose calls last year alone, something the agency just this month pledged to address with smaller, two-person teams from Community Health Assess and Treat (CHAT).

'IT'S A TRAGEDY, FRANKLY': Portland Fire launches new strategy for responding to downtown overdose calls

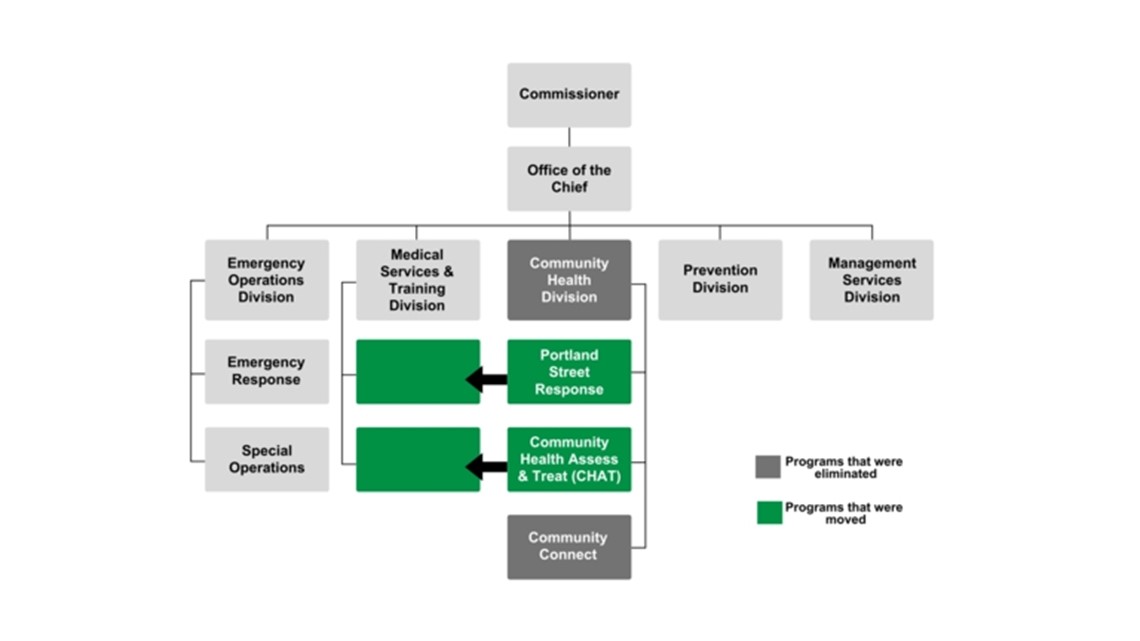

CHAT is one of three programs that were housed under the Fire Bureau's Community Health Division, created in Sept. 2021. The other two were Portland Street Response and Community Connect. While the three programs have obvious areas of overlap — namely that they were created primarily to address Portland's growing community of unsheltered homeless people — each one was intended to have a distinct mission.

CHAT teams consist of two community health medical responders driving in a Fire Bureau SUV or fire rescue truck to low-acuity medical calls. PF&R created the program with the help of grants from CareOregon, with the goal of triaging these calls in the field instead of taking people to the emergency room for assessment.

Portland Street Response, on the other hand, was intended by the Fire Bureau's last leader, Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, to be a non-police alternative for behavioral health-related calls among the homeless population, usually the kind dispatched as welfare checks. PSR sends at least one medical responder and one mental health crisis responder, sometimes accompanied by other specialists, in their own vans. It's largely funded by the city and federal grants.

Community Connect, the smallest of the three units, was supposed to follow up with people contacted by the PSR and CHAT teams and help them reach social services or ongoing health care. It's been funded through the same channels as PSR.

What are the community health teams for?

Field work for the audit ended in May of last year, and auditors note ruefully that it hasn't entirely aged well. Fire Bureau leadership dissolved the Community Health Division in July.

Since then, CHAT and PSR have been shuffled over to the Fire Bureau's Medical Services & Training Division, while Community Connect was dissolved completely, along with the division. Fire officials told the auditors that this follow-up work is now being handled by other staff elsewhere in the bureau.

Hours for the Fire Bureau's CHAT team were reduced from 14 hours a day during the audit to 10.5 hours a day now, Monday through Thursday. Though Portland City Council approved funding for PSR to expand to 24/7 service — a major goal for the program since it expanded citywide — it's still only operating 14.5 hours per day.

The auditor's report details how, prior to its dissolution, the division struggled with a lack of leadership from agency officials, little in the way of clearly identified goals — and thus, no overarching plan to meet them — and a perception that the Fire Bureau isn't committed to seeing them succeed.

"It is vital for government programs — especially new ones with important missions — to have clear goals so that staff, elected officials and the public understand what the programs seek to achieve," the report says. "Our audit found that while specific goals existed for the programs that made up the Community Health Division, the Fire Bureau had not established clear goals for the Division overall."

A 2023-24 budget request spelled out that the division was supposed to "address the increase in low-acuity call volume across the city," something that auditors noted finding in other documents for both CHAT and PSR, but some Fire Bureau officials said the community health programs were completely divorced from decreasing firefighter workload.

"We ... encountered a disconnect between a concern that traditional fire crews have been asked to go on more calls that involve people struggling with unmet medical and mental health needs and a recognition that the programs of the Community Health Division could help alleviate that burden," the report states. "That was especially true in the case of Portland Street Response."

'Slow down to speed up'

The Fire Bureau formed the Community Health Division back when it was headed by then-Commissioner Hardesty. Since early 2023, it's been the domain of Commissioner Rene Gonzalez, who voters chose over Hardesty in the November 2022 election. Meanwhile, Ryan Gillespie became interim fire chief in July after former chief Sara Boone retired.

In letters of response to Auditor Simone Rede, both Gonzalez and Gillespie pointed fingers at the former regime for the lack of leadership in the now-defunct Community Health Division, and argued that its dissolution is part of a strategy to right those wrongs. Gillespie suggested that the leadership problems at the division came to an end when he took charge of it in late March, just prior to the end of audit field work in May.

Above all, they accused the city and the Fire Bureau under Hardesty of trying to expand these programs too quickly, something they expressed pride in having halted.

"The specific programmatic opportunities for improvement your team identified reflect a desire on the part of previous elected leadership to expand Community Health as quickly as possible," Gonzalez wrote. "While the urgency may be understandable, the need to ensure these programs are structurally sound, grounded in articulable, actionable goals, and financially cost-effective can no longer be ignored.

"As commissioner in charge of Portland Fire & Rescue, I am committed to these programs' long-term success and have full confidence in both bureau and program leadership to guide us there. Your audit serves as an important reminder that sometimes we need to 'slow down to speed up.'"

In his letter, Gillespie hinted at how much ambivalence these programs have faced in the Fire Bureau — particularly the embattled Portland Street Response, which he framed as having been foisted on the Fire Bureau without enough of their input.

"The lack of an adequate safety net for people experiencing mental illness or struggling with substance abuse placed extra pressure on our programs to expand, which was often done at a reckless and irresponsible pace due to external influences beyond the bureau’s control," the fire chief wrote.

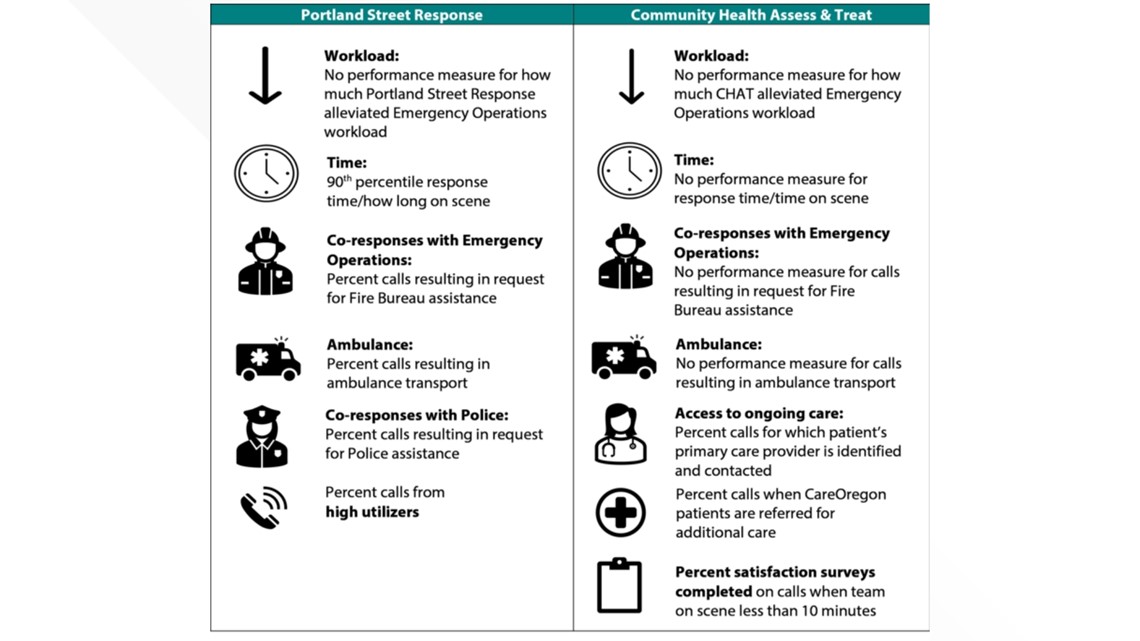

Gillespie made clear that he, at least, doesn't believe that the goal of community health programs like CHAT or PSR is to take some of that burden from firefighters. Instead, their goals are their own — particularly PSR's.

"The common denominator between PSR and CHAT is that neither program was designed to reduce firefighter workload," Gillespie said. "While CHAT does provide frontline crews with some relief from lower-acuity medical calls, this is an added benefit of our relationship with CareOregon, not a CHAT program goal or performance metric of our agreement."

By folding the former Community Health Division programs into another division, Gillespie argued, the Fire Bureau killed two birds with one stone; ensuring that they'd have a built-in leadership structure and eroding cultural differences that have separated these responders from the rest of the bureau.

The auditor's office noted that Gonzalez and Gillespie "generally agreed" with the report's recommendations, with the notable exception of the concept that the community health programs have a goal of reducing firefighter workload.