PORTLAND, Ore. — With Portland set to undergo a political transformation first thing next year, Mayor Ted Wheeler has been pushing hard to put as many of the pieces in place as possible ahead of time. He's picked the city's chief administrative officer, Michael Jordan, to take on the role of city administrator in this mock-up of the new administration.

Jordan has made abundantly clear that while he's committed to facilitating this transition, he does not want to be Portland city administrator for any longer than he has to be. That said, he may be doing the lion's share of the work before his permanent replacement comes along and takes the reins.

What charter reform hath wrought

Portland voters approved the change-up in November 2022, agreeing to alter the city's form of government for the first time since 1913.

Under the old system, four city commissioners and the mayor are responsible for creating policy, but they also oversee the day-to-day operations of multiple city bureaus and their hundreds of employees. That makes for a fairly big job for each elected official, people who do not necessarily have any experience in public administration or the portfolios they're placed over, and with millions of dollars on the line.

Over time, just about everyone now seems to agree, this commission-style system resulted in the bureaus becoming siloed — resulting in poor communication and cooperation. City staff were only really beholden to the commissioner in charge of their bureau, rather than the mayor or the government as a whole.

As the city grew, Portland's city bureaucracy became more disjointed, cumbersome and often ineffective.

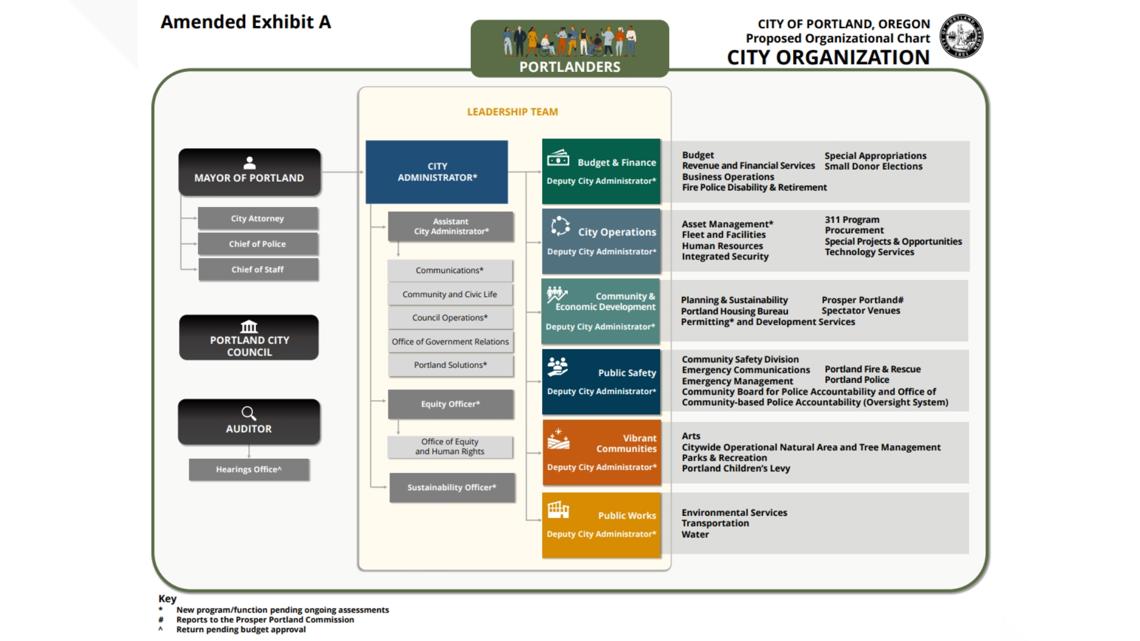

Under the new system passed by voters, city commissioners will focus only on creating and passing policy. They'll be entirely hands-off with the city departments. Instead, a professional city manager will take over the administration, assisted by six deputies.

The existing 33 bureaus and offices will be consolidated into just six areas. The mayor, meanwhile, will be charged with overseeing the administration, with the power to hire and fire the city manager and police chief.

City commissioner ranks will expand to 12, or three people each from four quadrants of the city. They'll be elected in November and take office at the beginning of January 2025.

However, consolidation of city bureaus is supposed to happen July 1 as the current government attempts to transition into the overall shape of what it will be next year. While the current city commissioners will still technically be in charge, deputy city managers will begin to run the six different departments under the direction of the interim city manager, Michael Jordan.

The city that permits

The transition will coincide with Portland's new budget, which begins July 1. Jordan told The Story's Pat Dooris that this gives the city something like a six-month runway to get this new form of government off the ground.

"On July 1 we'll, for lack of a better term, begin practicing how the city will operate in the future under a new mayor and a new city council in January of '25," Jordan said. "We've got a lot of questions to answer that are kind of the next level of detail questions. The thing that the council adopted back in November is really a large framework for the whole city. But a bunch of detailed questions are buried in that framework that need to be answered in the next cycle of change."

Getting even that overall framework through Portland City Council was a fraught process, and the battles continue. As Willamette Week reported, Commissioners Carmen Rubio and Mingus Mapps were recently at odds, as both oversee bureaus that handle permitting. Under the new system, they'll all be under one umbrella — and they'd arguably have been consolidated even without charter reform due to long-running complaints about Portland's byzantine permitting process.

Mapps wanted to slow the consolidation process due to concerns from people in his bureaus who felt it wasn't clear who they'd be reporting to, he said. Rubio flatly refused.

According to Jordan, this consolidation is an example of the kind of change that needs to happen in city government.

"It is a little awkward, but it's also an example of the kinds of examination of how we do business that I think will be easier to do under the new structure, where you'll have one person that's kind of accountable to the whole thing and one place where the buck stops," he said. "This work we've done at restructuring permitting, that goes into effect also July 1, it involves seven different bureaus reporting to all five different commissioners. And so trying to manage that kind of change with very fragmented leadership at the very top, it presents its own set of complications. Let's put it that way.

"In the future, when we do things like that, we'll just have one city administrator that will be calling the shot, and there may be multiple deputies involved, but they're all accountable to that one city administrator who's ultimately accountable to the mayor also."

There are reasons why the permitting process was so divided in the first place. When someone applies for a development permit, Jordan explained, the Portland Fire Bureau is in charge of life and safety and the Water Bureau naturally handles water. Environmental Services deals with storm drainage and environmental review, while the old Bureau of Development Services dealt with state building code and inspections.

Each bureau has a singular focus, so it made a certain kind of sense for each to oversee the permitting under their purview. But that structure created a lengthy gauntlet that developers need to run for any single project, throwing up roadblocks all over the place.

RELATED: With new bureau, Portland attempts to streamline residential, commercial permitting process

"It's been recognized for decades," Jordan said of the permitting problems. "But this commission ... it's laudable that this commission, with four of them running for office and all of the things that that comes with, they've been very focused on changing this permitting process and getting all the people involved in a building permit working in one bureau with a single director accountable to all of those issues."

It won't necessarily be smooth sailing from here on, Jordan admitted. Bundling permits creates other potential issues. Regardless, the idea is that the city will be more responsive to the needs of everyone, particularly the folks who aren't experienced with navigating a bureaucracy like this.

"We have had, historically, a lot of people who do development in the city, that do it all the time, and they've got attorneys and they've got planners and they've got engineers that do this stuff for them, and they understand the process," Jordan said. "But I think the people we struggle with the most are mom and pop, who want to expand their business and they'll do it once in their life. And they don't know anything about this process and we have to find a way to get them through what can be a very convoluted set of decisions that have to be made."

Most permits the city gets are of the "mom and pop" kind, Jordan added, so the city needs to be attentive to what they need.

Trimming the fat

Once the city siloes are knocked down, Jordan and others in this interim administration will be trying to figure out where the inefficiencies are. Partly, that will entail looking for redundancies — and some jobs may be going away because of it.

As an example, Jordan said that each of the city bureaus have grown their own in-house communications teams due to the fact that they're not sharing notes. All told, he thinks there are at least 80 people doing this kind of work throughout the city.

First, they'll need to figure out how these communications teams can integrate and start working together.

"We have probably 20, maybe more comms folks in public works, in the three big infrastructure bureaus — transportation water and sewer — and none in budget and finance," Jordan said. "That's just an example of, maybe we need to think about the distribution of those resources. Also, consolidating them under one authority, one person allows us to move resource more fluidly. Say we have a communications crisis thing to manage in one of the bureaus, and they don't have the capacity. We can move people and say, 'OK, next three months you're working over here, and you need to manage this issue.' And so we struggle with the fluidity of how to apply human resources."

Jordan said he's not here to propose layoffs, but he expects that some vacant positions may get eliminated as people retire or leave for other jobs. That'll be part of a long-term effort to "right-size" the new city government.

But, Jordan acknowledges, this will be a process of discovery. He's been the city's chief administrative officer, and that isn't the same as a city manager. He knows the Office of Management Finance, his department, but he doesn't know the transportation, fire, police or parks bureaus anywhere near as well.

"We're gonna find out a lot with each other. We're gonna do this together," he said. "It won't just be the six (deputy) city administrators. We will work with the directors of bureaus, and then we'll also have to work with those subject matter experts. Depending on what the discipline is, whether it's comms or equity or whatever. And we'll work with those people and bureaus, and we'll get a good sense of, 'OK, what do you do? How much time does it take? What's the volume of work,' all those kinds of things, and then start to think about, 'OK, let's start to think about how we right-size and how we apply human resource in the best way possible.'"