PORTLAND, Ore. — Earlier this week, Gov. Tina Kotek convened the first meeting for a task force of 40 people focused on the problems facing Portland's economic core. They're tasked with finding solutions for those problems and providing a plan of action by the end of this year.

Reporters are excluded from these meetings so that members of the task force can talk freely, and it's not entirely clear what came up during this first session. However, Gov. Kotek's office was kind enough to provide the PowerPoint slides highlighted during the meeting, which lay out data on some of Portland's biggest problems. Most of the information comes from Michael Wilkerson at the consulting firm ECONorthwest.

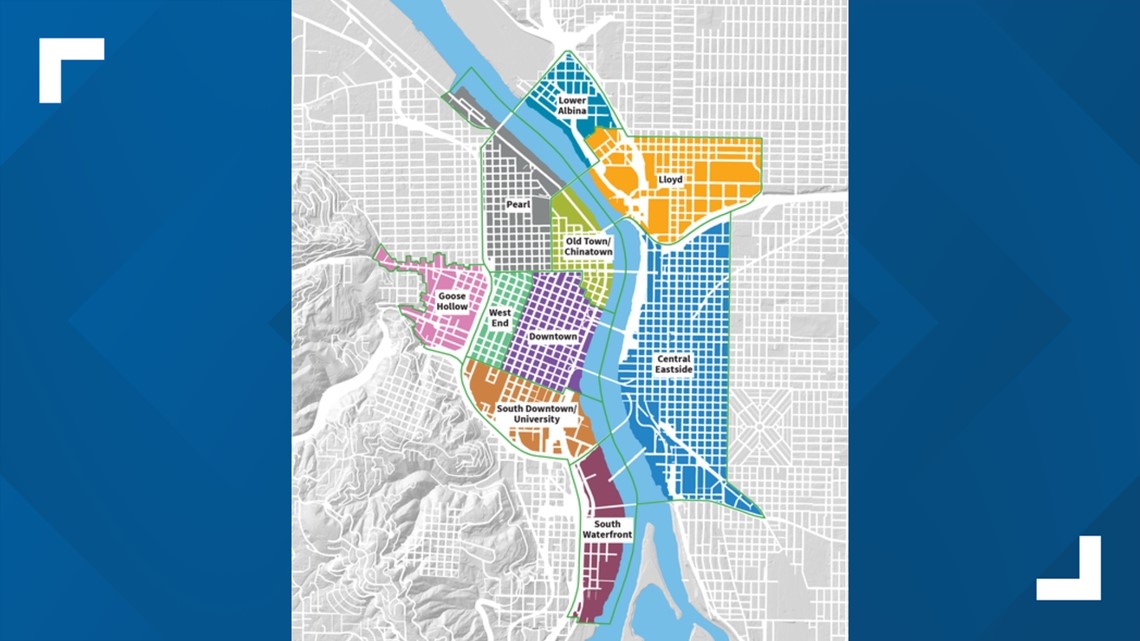

First, it's worth noting that the scope of the task force's mission is limited to Portland's central city, which is a larger area than just downtown or the central business district. It stretches from Lower Albina in the north all the way down to the South Waterfront, including Goose Hollow and extending east to include all of the Lloyd District and the Central Eastside.

Exodus and earnings

The research starts with an overview of Multnomah County's declining population. Population growth in the Portland area started to slide even prior to the pandemic, hitting its high water mark in 2016. By 2021 it had moved into the negative, falling even further in 2022 as more people moved out of the area.

While it's reasonable to point out that other metropolitan areas took a similar hit during the pandemic, that isn't the full story. The greater Seattle area also hit its population high water mark in 2016 before beginning to slide, going negative in 2021 as more people left than moved in. But last year, Seattle started to bounce back. Portland hasn't rallied in the same way.

Salt Lake City had a similar drop in migration to the city, but other cities of comparable size to Portland did not, including Austin, Indianapolis and Nashville.

When looking purely at population loss from 2020 to 2021, Portland tied for fifth place with St. Paul, Minn. In fact, Detroit, Mich. narrowly beat Portland.

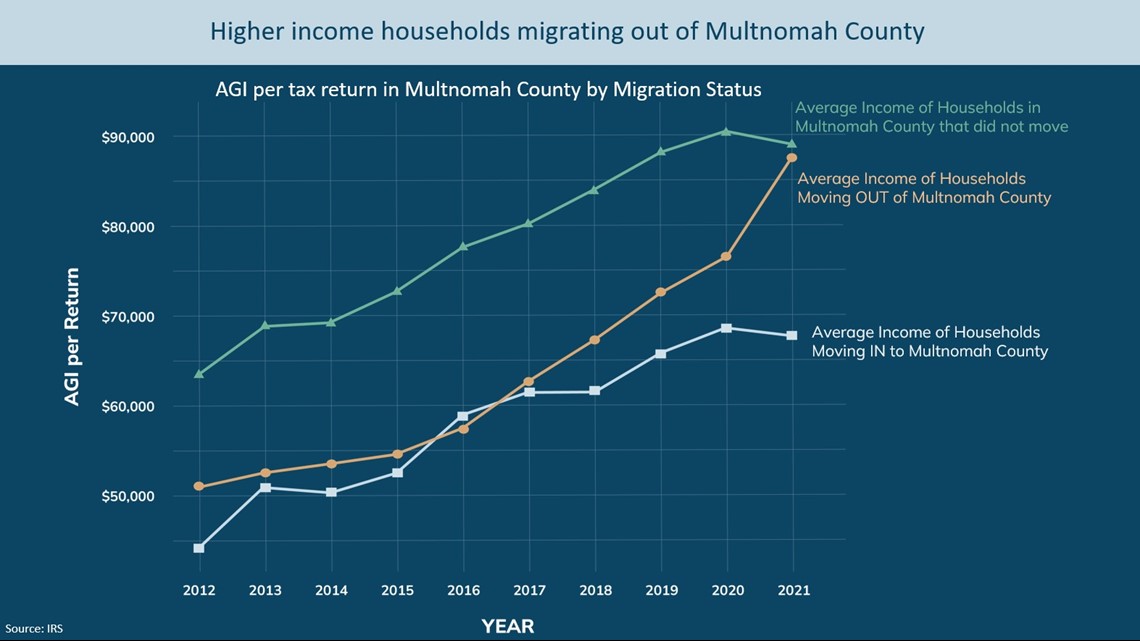

Then there's the loss in income. From 2012 through 2020, people moving into Multnomah County from other states brought millions worth of income with them. In 2020 alone, that amount was $230 million in new income. But in 2021, that trend reversed. At that point, it was nothing but money leaving the county.

Between 2015 and 2017, the income levels of people coming to Multnomah County and those leaving were about the same. But that started to shift in 2018, as high earners leaving the area were replaced by lower earners moving in. According to ECONorthwest's data, the people leaving in 2021 were making an average of over $85,000 a year. The migration out of Multnomah County resulted in a loss of more than $1 billion.

At the same time, data from Earnst and Young shows Portland with the second highest income tax in the nation for people or couples making over $150,000. While New York City technically has the highest income tax, their top rates don't kick in until people start making $25 million a year.

The elephant in the room

The task force presentation spends a lot of time on the central city's slump in foot traffic, in-person work and hotel stays — particularly in downtown — and the fact that there's just not enough housing in the area compared to the amount of jobs ostensibly based there.

Kotek and task force co-chair Dan McMillan, CEO of Portland-based insurance company The Standard, have both pointed to the central city's glut of office space compared to available housing as one big issue impacting recovery.

"The types of challenges facing Portland are similar in other large cities," Kotek said during a Tuesday press conference, "particularly cities like ours, which has been very focused on a downtown core that's very office-centric. The pandemic has changed that norm, and so we're trying to figure out what does that mean for us going forward?"

But the level of unsheltered homelessness sets Portland apart from some other cities, Kotek acknowledged. According to one slide from the presentation, Multnomah County's homeless population is more than four times greater than the U.S. average. The county holds about 2.6% of the nation's unsheltered and chronically homeless people, but only 0.2% of its residents.

Then there's another big issue facing a central city comeback: crime. According to task force data on seven areas of the city, offenses are down slightly this year from 2022 in every area but downtown. However, total offenses across all of those neighborhoods are down significantly from last year, if still higher than in 2019, 2020 or 2021.

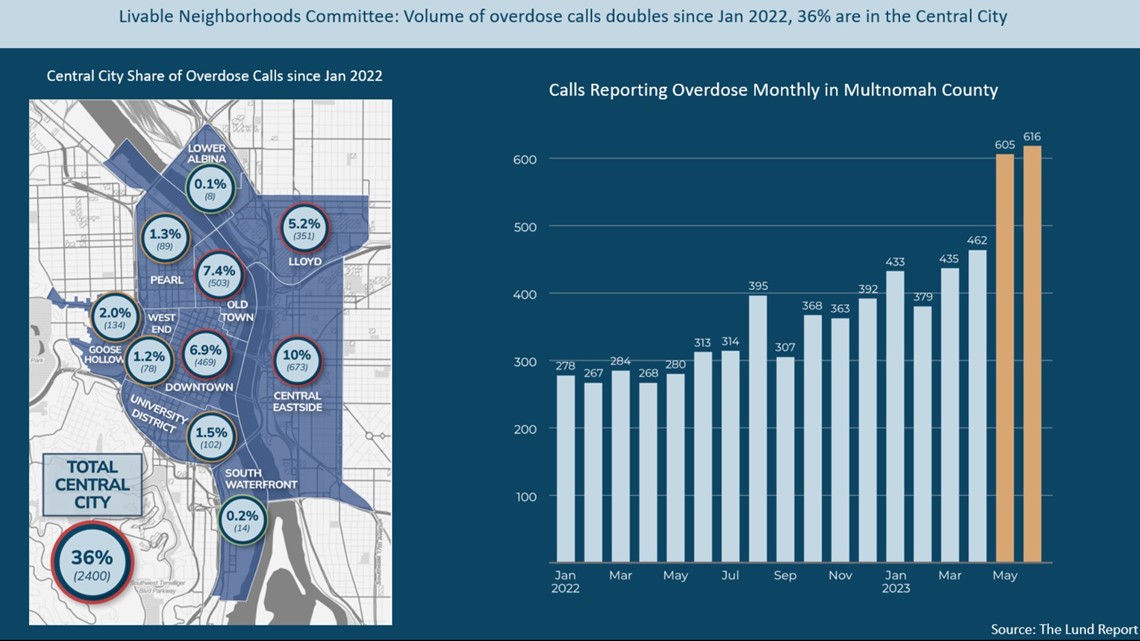

Meanwhile, monthly overdose calls have more than doubled in the central city since last January, from 278 to 616, and are particularly high in the Central Eastside, Old Town, downtown and the Lloyd District.

With all that in mind, the task force has been split into five different committees: Central City Value Proposition, Livable Neighborhoods, Community Safety, Housing and Homelessness, and Taxes for Services. Each one has been given a mission that they're supposed to work toward, with meetings monthly until they deliver a full action plan in December.

The Story airs at 6:30 p.m. every weekday on KGW. Got a question or comment for the team? Shoot an email to thestory@kgw.com or call and leave a voicemail at 503-226-5090.