PORTLAND, Ore. — When a city the size of Portland gets soaked with rain like it has for the past week, there's a concern that often lurks under the surface of the flooding and slide risks: sewage. The prospect of sewage flowing into local waterways never quite goes away, but it's thankfully an exception rather than a rule these days.

That's all thanks to Portland's "Big Pipe" system. Built over 20 years, the Big Pipe radically changed water quality for the Willamette River when hard rains fall on Portland.

Portland's first sewage treatment plant opened in 1952. Back then, the city had a combined sewer system, meaning the sewage combined with storm water and traveled along the same pipes.

During relatively dry stretches, that system worked alright. The drains and pipes collected both rainwater and sewage, sending both to the treatment plant. But problems arose whenever the city got drenched. All the runoff from streets, roofs and parking lots would drain into the combined system and overwhelm it, ultimately bound for overflow pipes that shot the whole mess right into the Willamette River.

The city estimates that overflows like this consist of about 80% stormwater and 20% sewage. On average, it happened about 50 times a year back then, spewing 6 billion gallons of liquid into the Willamette River and the Willamette Slough each year.

It should go without saying that having that waste flowing out into local waterways is not a good thing. Among other things, sewage can contain the bacteria E. coli, which is harmful for humans and the environment alike.

So, in 1991, the city and Oregon's Department of Environmental Quality entered into a legal agreement committing the city to a fix for the problem.

It started with triage before Portland got to the big operation. First, the city started a campaign to cut down the amount of storm water going into sewers. They eventually convinced people on the city's east side to disconnect 56,000 downspouts, redirecting that water into the soil instead of the sewer. That kept an estimated billion gallons of water out of the system.

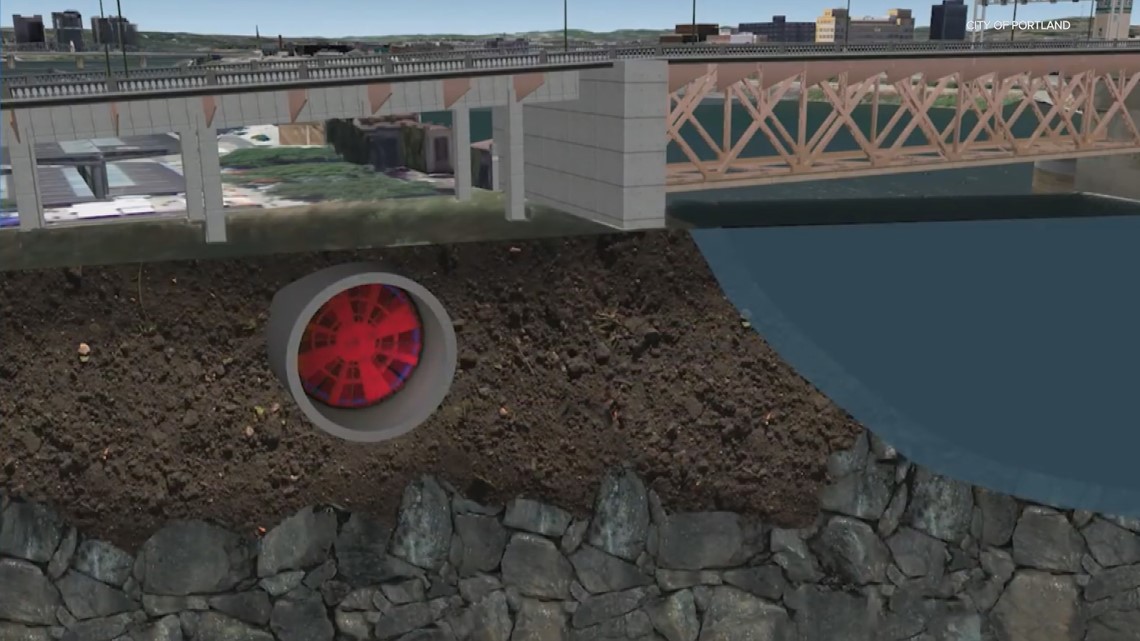

Portland then set out to build massive pipes on either side of the Willamette River that could hold all the extra water from storms, pumping it to the sewage plant as soon as there was room. A later part of the project expanded the sewage treatment plant so it could handle the extra flows.

The travels of Lewis and Clark

The first construction project focused on the Columbia Slough. The city put down a pipe from 6 to 12 feet in diameter and 3.5 miles long, running next to the slough in order to capture combined sewer overflows there. And according to the city of Portland, the big pipe works — it's able to stop 99% of overflows.

Next, the city started building a huge pipeline on the west side, which proved much more complicated. Two massive boring machines, dubbed Lewis and Clark, went to work 120 feet below the surface, tunneling north and south. They bored a tunnel 14 feet in diameter and 3.5 miles long, running along the Willamette's west bank and under the river to Swan Island on the northeast side.

The tunnel's path took it under most of Portland's bridges. It also went under Waterfront Park, where crews injected concrete into the ground to protect against settlement as the boring machine passed underneath.

While the tunnel was big, the boring machines were even bigger. Their cutting heads measured 16 feet in diameter, and they plowed through the ground, chewing through dirt and rock. All that debris was carried out to the surface and later barged upriver to help restore Ross Island Lagoon.

As the boring machines progressed, hydraulic arms behind the cutting heads installed pre-cast steel-reinforced segments to create the tunnel rings — a tunnel big enough that a Greyhound bus would fit inside with room to spare.

But even with all that room, the water and sewage collected by the westside pipe needs somewhere to go. So, crews built a huge pump station on Swan Island to move the waste along to Portland's main sewage treatment plant. The pump station itself is 123 in diameter and 160 feet deep, as big as a 15-story building.

During wet weather of the kind that hit Portland this week, the pump station can move 100 million gallons of water and sewage each day.

After the west side was finished, work began on the even larger east side pipe. It's 22 feet in diameter and nearly six miles long, tall enough for a giraffe to crane its neck within.

Construction methods on the east side pipe were similar to the west side, except contractors used one enormous boring machine instead of the two smaller ones. It occasionally had to alter course to avoid the freeway bridge footings, but the city of Portland says that super-accurate laser guidance systems led the machine to within an inch of its intendent target at all times.

Overflow-free, mostly

Portland's herculean effort began in earnest in 2000 and wrapped in 2011, costing about $1.4 billion. The end result is that these combined overflows of sewage and storm water are much less common post-completion. But even with these massive pipes serving as storage tanks, overflows still happen.

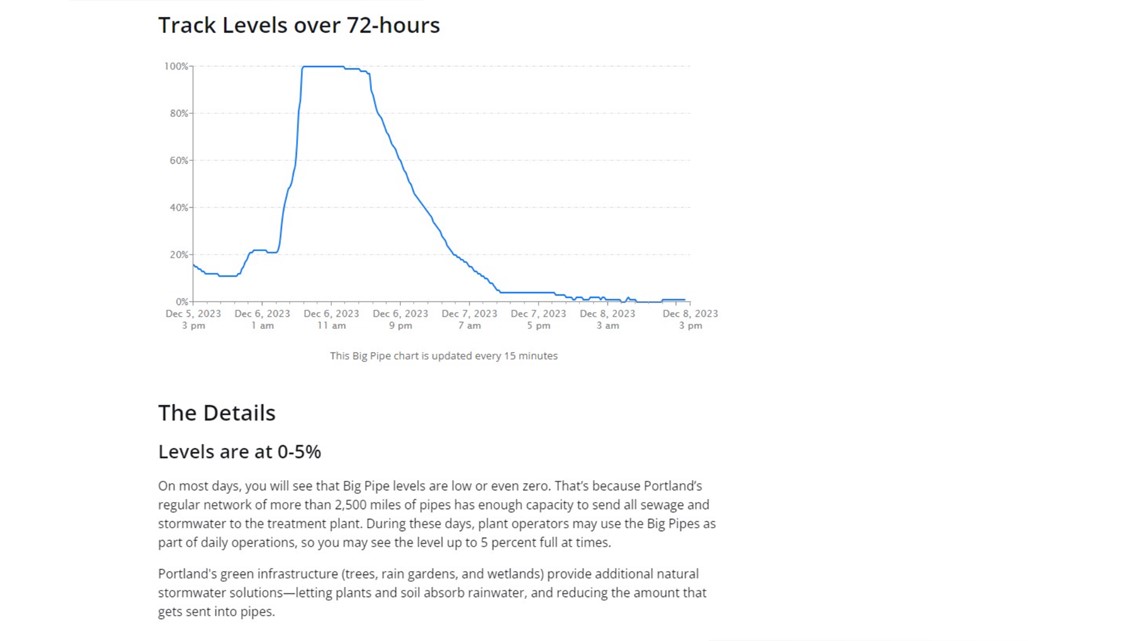

The city of Portland is able to track levels within the tunnels and determine when overflows are happening — when levels hit 100%. The last one occurred earlier this week, starting around 7 a.m. on Wednesday and lasting until roughly 6 p.m. that evening when levels drifted down.

According to the city, the big pipe system had prevented more than 300 million gallons of wastewater from reaching the river between Sunday and Tuesday, before it was ultimately overwhelmed.

Portland's "Big Pipe Tracker" is updated every 15 minutes, and showed that the tunnels were nearly empty as of Friday afternoon, only about 1% full.

Sewage flows into the Willamette seem to occur a few times a year, big pipe or no. In October, the city said that about 11,000 gallons of wastewater were released into the river due an equipment issue at a pump station. But there was an overflow due to overcapacity in March, at least one similar incident in early 2022, and it happened at least five times in 2021.