PORTLAND, Ore. — If utility company Portland General Electric gets the approval of regulators, 2025 will be the fifth year since 2020 where customers saw a rate increase. But it will also coincide with growing concerns that high-tech infrastructure, namely big data centers, could be having an outsized impact on power costs.

In late November, U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden penned a letter to PGE's CEO, questioning why the company would seek a rate hike in 2025 with a 40% increase in prices since 2020 already on the books. The request of regulators made by PGE in July was for an increase of 10.9%, though it's since been revised down to something like 7.9%.

PGE CEO Maria Pope's response to Wyden was instructive — not just in terms of the overall rise in power cost and demand, but the way high-tech industries have not been well accounted for by Oregon's regulatory landscape.

According to Pope's letter, the purchasing and production costs of power have been the primary driver behind rate increases over the last four years, followed by the company's investments in upgraded infrastructure. Those were compounded by major climatic events, like the 2020 Labor Day fires, the 2021 heat dome and several significant ice storms.

But part of the reason why power costs are so high is that demand has been surging at the same time that utilities are moving toward cleaner sources of energy. And that increase in demand is not happening among all customers equally — the fastest-growing area for load growth is in the high-tech sector, as Pope admits.

"Like utilities nationwide, PGE is experiencing a surge in requests for new, substantial amounts of electricity load, including from advanced manufacturing, data centers and AI-related companies," Pope said. "This comes at a time when we are investing in a system to withstand increasingly extreme weather, support increasing electrification and enhance access to the lowest cost renewable energy available."

By PGE's numbers, overall demand for electricity grew about 10% between 2019 and 2023 — a huge spike, considering that the previous 10 years saw growth of only 2.8%.

In the last five years, PGE said, residential energy deliveries grew by 6.4%, or 5.2% when adjusted for weather. That was largely tied to customer count, which increased 4.6% during that period. Growth in commercial energy deliveries was lower — which PGE attributed to increased energy efficiency and a shift to online retail — amounting to 1.9%, or 2.7% on a weather-adjusted basis.

But industrial energy deliveries soared, growing 34.7%, or 34.3% when adjusted for weather.

"PGE's service area semiconductor manufacturing and data center segments are driving this growth," Pope wrote.

Pope argued that overall load growth actually helps affordability, "because the more people using the grid, the more the costs to operate the grid are spread out."

At the same time, however, Pope seemed to acknowledge that current regulations under the Oregon Public Utility Commission might not account for disparities in where demand is growing the most, or where the bulk of PGE's infrastructure investments are going.

"Existing regulatory frameworks will need to evolve to appropriately reflect how investments serve different customers and how costs are allocated given the changes in the new large load demands," Pope said. "Collaboration with regulators, policymakers and stakeholders is essential to help address these new realities and to keep the price of electricity as low as possible for residential and other business customers.

"This cooperation is underway, and PGE remains actively engaged with Oregon’s stakeholders to address cost allocation, including for new large requests for power."

The cooperation underway

A spokesperson for the Oregon PUC confirmed in a statement that they are "actively analyzing" new ways to account for the rise of industrial power customers, but the regulatory body said that data centers are not yet known to be a big driver of rate increases.

Some of Oregon's biggest hotspots for data centers these days are along the Columbia River well east of Portland, like Google's holdings in The Dalles or Amazon's in Boardman — outside of PGE's service area. But PGE does service Hillsboro, which has long been a bastion for high-tech industries, including a growing number of data centers.

The Oregon PUC will soon decide whether to approve PGE's latest rate hike, which would go into effect Jan. 1, 2025. A spokesperson reiterated that those rate increases "would not be driven by costs that we have traced back to new, large load/data center customers."

In response to a request for comment, PGE echoed what Pope and regulators had to say:

"It is important to note that large customer growth is not a significant driver of rate increases to date. Rather, changes to customer rates over the previous few years are due to the rising cost to purchase power on the open market and substantial infrastructure investments to reliably serve all customers.

"With the increase in new large requests for power, collaboration is underway with regulators, policymakers and stakeholders to safeguard residential customers and address cost allocation."

Critics aren't so sure that these rate increases can be divorced from the rise of big industrial customers. Regardless, it's highly unlikely that any new regulations on those types of customers will go into effect before that rate increase does. Currently, the regulatory commission has three dockets open with PGE related to data centers and tech manufacturers, and several for Pacific Power, but it's unclear when any of them will be resolved.

"The Commission’s current approach to rate recovery aims to ensure that customers are fairly paying for the costs they impose on the system," the Oregon PUC spokesperson said. "The PUC will review proposals to update PGE’s tariff for connecting large customers to ensure that PGE fairly assigns the risks and costs of this level of demand."

The PUC is considering things like adjustments to the "line extension allowance," which refers to subsidies which new power customers receive for starting service, paid for by existing customers. Very large customers like data centers could be made to pay a higher share upfront to join the grid than other, smaller customers — something that is not currently the case.

The Oregonian's Mike Rogoway reported in October that data centers already account for an estimated 11% of Oregon's power consumption — more than twice as much as all the homes in Portland. And that consumption is expected to double, perhaps triple or quadruple, by the end of the decade, he reported.

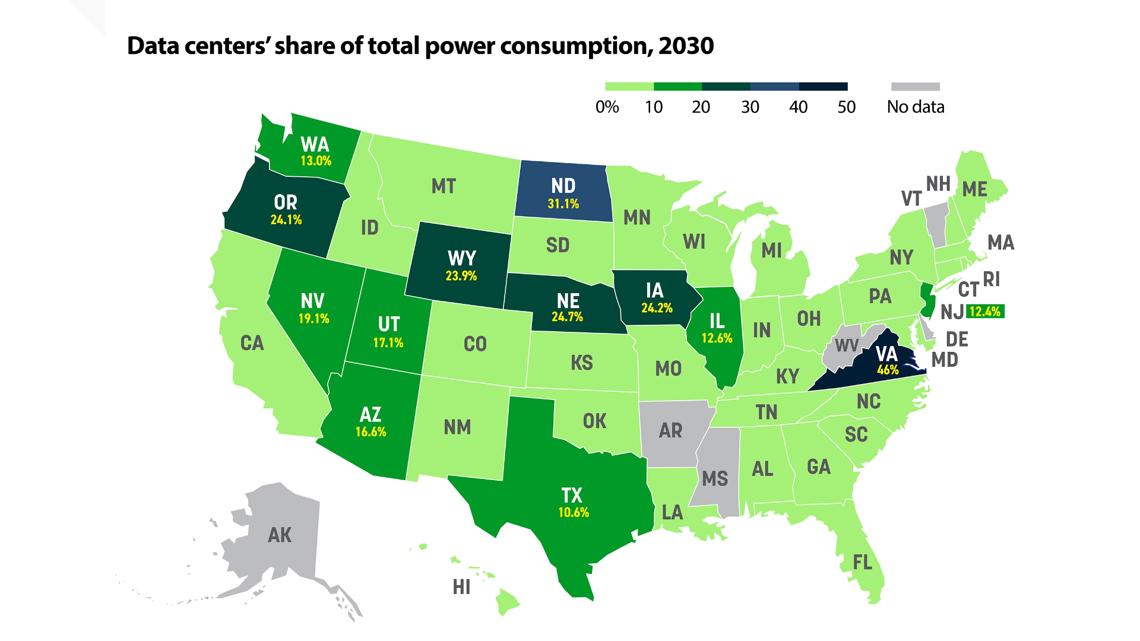

While Oregon isn't alone in this spike, it is one of the top destinations in the U.S. for these data centers, lured in by big tax breaks. A think tank called the Electric Power Research Institute placed Oregon among the five highest states in the nation for data center power demand. Data centers are expected to account for 24% of Oregon's power consumption by 2030, according to EPRI.

Data centers have been necessary infrastructure for any number of tech-related industries for many years now, but there's a singular reason why they are exploding in growth now: artificial intelligence. AI requires immense processing power, so the machine learning gold rush already underway is being built on the backs of data centers.

Sharing the load

The extent to which rising rates are being driven by growth in this sector can be hard to separate out. But according to Bob Jenks, executive director of the consumer advocacy group Oregon Citizens' Utility Board, there's no question that data centers are unfairly driving up costs, and in multiple ways.

"Right now, PGE has more data center load just in the city of Hillsboro than all the load of all residential customers in Washington County," Jenks said. "And Washington County is obviously Oregon's second largest county."

Over the last decade, increased energy efficiency across PGE's customer base would have actually resulted in load reduction, Jenks said, if it weren't for the boom in things like data centers — really, just a handful of customers.

"So, the idea that we sort of socialize and all people pay for load growth (at one time) made sense because all customer classes were seeing load growth," Jenks said. "But nowadays, we're only seeing the load growth happening really in the data center in the large industrial sector."

READ MORE: To meet clean energy goals, the West Coast will need to produce, store and share more power

The cost of actually hooking up the data centers to power is one aspect of the cost that all customers bear, through things like the aforementioned line extension allowance. But, Jenks said, there's a lot more new infrastructure that large industrial customers require.

"PGE is doing all kinds of upgrades in its transmission system that seem to all be designed to get power into Hillsboro, get more power into Hillsboro, which is where all this data center load is," Jenks said. "And the problem with that is those transmission upgrades then go into the transmission revenue requirement, which then spreads the cost among all classes of customers."

And beyond infrastructure, there's the way these data centers can drive up the cost of power more generally, through production and purchasing, which PGE has cited as the primary driver of rate increases for the last several years.

Load growth means more demand for power. And that's complicated by Oregon's drive toward clean energy, Jenks said. While existing customers might have been largely supported by existing cheaper sources of power — hydroelectric, for example — as these new industrial customers drive up load growth, utility companies are forced to acquire higher-cost power in order to meet both demand and climate obligations.

"So, all that load growth that's coming in has to come in at 100% clean, and that's problematic," Jenks said. "You can do a lot in the summer with solar and batteries, but in the winter, what's the clean energy that's going to serve our Facebook facilities in the middle of January? If we have a couple of days where the wind is not blowing, we don't have batteries that last that long."

'ON THE EDGE OF AN ENERGY CRISIS': Forecasting the future of electricity in the Pacific Northwest

Despite the admissions in Pope's letter of response to Sen. Wyden that costs may not be borne fairly under existing structures, PGE has made the opposite claim that Jenks does in its filings to regulators, according to the Oregon PUC's docket. Data centers are making power more affordable to all customers, the argument goes, because they provide a very stable source of load, instead of fluctuating like residential customers do.

"I think that's absurd. This is highly inflexible load," Jenks countered. "This is a really difficult load to serve, because it's going to be there at a significant level — it's 24 hours a day, 365 days a year at a pretty high level. They say it doesn't have a peak load. Well, the way I look at it, it's always a peak load, it's always really high and it's all the time."

Residential load fluctuates based on need, Jenks said, both by time of day and by time of year. In the winter, people need heat, particularly in the mornings. In the summer, they need cooling and particularly in the evenings. But data centers always need what they need — a lot of power. It doesn't matter if an ice storm and below-freezing temperatures are pushing the power grid to the brink and residential customers are being asked to limit their use. Data centers still need that power.

"And they're doing it with intermittent resources, to do it with wind and solar and power that varies is really, really difficult, and their load doesn't vary and offset that," Jenks said. "When do you charge a battery to serve a data center when the data center load never goes down? For residential customers, at night you can charge batteries; in the daytime (around noon, when usage is low)."

There's also a built-in assumption, Jenks mentioned, that these data centers are in it for the long-haul. But there's no guarantee that this AI-driven boom will continue, or that it will be worth it to them to stay. Data centers spring up quickly, and they can just as quickly pack up and leave.

A brewing backlash

Pacific Power has already taken steps to make data centers pick up more of the cost, actively requesting of the Oregon PUC that big customers not receive the line extension allowance that other customers do.

But PGE, Jenks said, is behind the times.

"Pacific Power has been much more aggressive at trying to identify these costs and trying to segregate them, trying to allocate them, make sure that they're being allocated to data centers and data centers are taking responsibilities for these," Jenks said. "I do think Pacific Power is at least two years ahead of PGE in thinking about this and trying to assign these costs and make sure this load growth is paying for itself."

The Oregon PUC is looking into all of this, but Jenks said it's too soon to tell if they'll come out with effective regulations that more fairly adjudicate these costs. The companies behind these data centers have lobbying groups dedicated to ensuring they don't have to shoulder more of the cost burden.

That goes for PGE's side in this, too, Jenks said.

"Remember, PGE makes money; they profit off of investments, capital investments," he said. "So, these all this data center growth in Hillsboro means PGE has got to put huge amounts of money into building up the transmission system, investing in new generation. All of this stuff is increasing PGE's profits going forward.

"So, I think PGE is slow in this game because they've been sort of cheerleading it and not being very transparent about the costs that are coming on the system and what they're caused by ... but it's hit a point where it's not going to work. There's a backlash from customers that's been brewing all year. It's going to turn on the data centers, it's going to continue to turn on PGE, and it now puts PGE in a situation where I think they have to manage this differently or ... the backlash is really going to start to harm them, and it's going to make it hard for data centers to locate here."

Alex Baumhardt, reporter for the Oregon Capital Chronicle, noted in a story Thursday that PGE stock rose 10% in the last year, while CEO Maria Pope's compensation doubled between 2020 and 2023, from $3.5 million to $7 million.

The Oregon PUC did proffer a potential defense of the daylight between Pacific Power and PGE thus far. Pacific Power covers larger, more remote areas, and infrastructure they put in place for data centers might not serve anyone else. Since PGE's service area is more urban, that infrastructure is going to serve other customers, even if it's being driven by growth in tech.

And Pacific Power is raising rates, too. Their request earlier this year was even larger that PGE's.

Regardless, PGE is at the table with regulators now. PUC's spokesperson said that PGE is "actively engaging and drafting a proposal which aims to address these risks in a way they see fit."

An energy industry publication called Clearing Up reported this week that PGE is exploring changes for big industrial customers, to possibly include charging them a mandatory minimum rate based on how much peak demand they put on the system, as well as requiring them to sign a contract to ensure they're in it for at least eight years.

Wherever the Oregon PUC comes down on these regulations, Jenks signaled that there's growing interest from Oregon lawmakers to deal with data centers through legislation. He said he expects it to come up in the coming 2025 session, which begins in late January.

"Residential customers have had between three and four times as much increase in their rates during that same 10-year period of time when all the growth is in the industrial customers," Jenks said. "And we just don't think that's supportable. It really is a sign that the costs of meeting this new load growth are being socialized and are hitting everyone, and we just can't ... we can't go on."