SALEM, Ore. — When Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek released her proposed budget on Tuesday, it did not include mention of the $500 million or so that experts say will be needed for the kind of land development that semiconductor manufacturers are looking for.

The Oregonian reported that Kotek plans to leave tax incentives and other issues around attracting tech companies up to state lawmakers.

But before the legislature can even get to those incentives, there remains the issue of where these huge plants could even be built. With Oregon's unique land use laws, there are no plots of lands considered viable right now.

Earlier this week the group that's been studying the issue for the state — including the Port of Portland's Keith Leavitt — made the point clear to lawmakers.

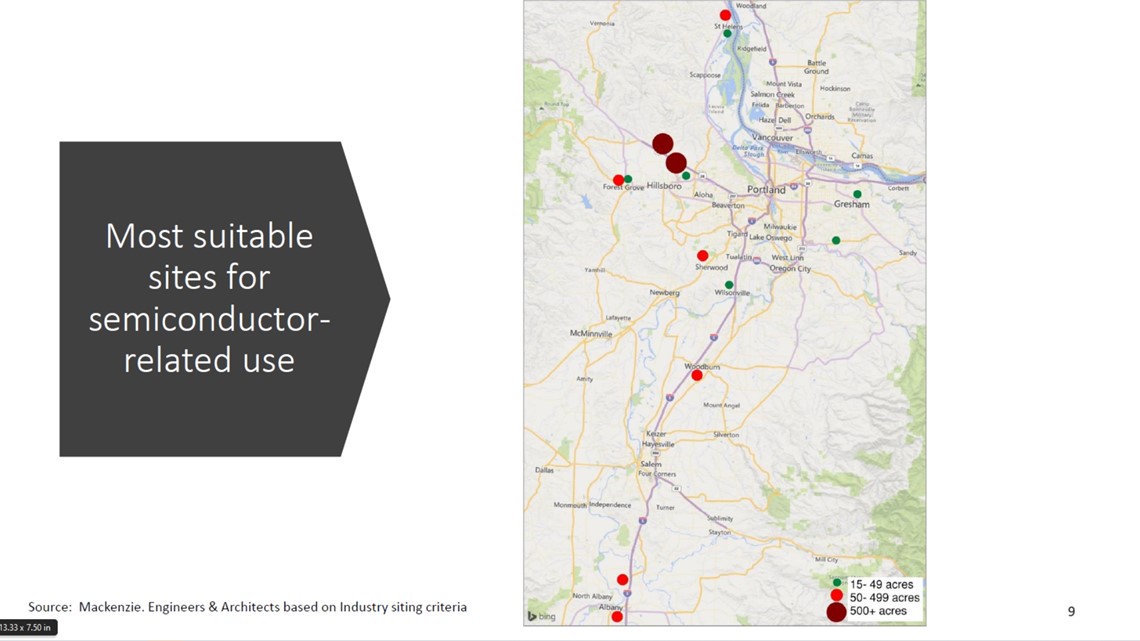

"The headliner is these 500-acre sites. We found none," Leavitt said. "And so we spent a lot of time understanding where communities are, who is interested in having these very large sites — and no surprise, the focus became in Washington County, in the north Hillsboro, the North Plains area. Both of those communities are engaged in urban growth boundary expansion processes — but not expansions to the level of bringing 500 acres in."

Leavitt said that a firm hired to look for suitable land checked out 74 different areas, from Medford to central Oregon and the Willamette Valley. They found just two possible locations for a 500-acre site, which they believe a semiconductor plant would need. Both were in the area around North Plains and Hillsboro.

Leavitt told lawmakers that it would not be politically easy to accomplish, but locking down these sites would be worth the effort.

"This is a sector that is unique among all of the industrial sectors in the state. There is really nothing that offers the volume of jobs and the quality of jobs — and then the economic equity opportunities," Leavitt said. "Because a lot of these jobs, nearly half of them, are accessible with a high school to community college degree and then you go all the way up the scale and we're attracting Phds from all over the world."

The term "economic equity" is likely to get a lot more mention as the debate over tech company incentives picks up steam in the months ahead. It's the idea that the semiconductor business pays particularly well, and those jobs can help people overcome economic disadvantages.

Gresham Mayor Travis Stovall had a similar point in support of the plan.

"When I think about the opportunity that exists here for us to look at our communities, and Gresham is at the forefront of this," Stovall began. "When we look at the household, the average household income, we don't have the opportunity to move forward until we have the jobs available throughout every single one of our communities. That is a critical component when we start talking about how do we give everyone the opportunity to go from poverty to prosperity."

But herein lies a coming clash of values, one between high tech jobs and Oregon farms.

'It was a deal'

Oregon's urban growth boundary draws lines around every city in the state. It's possible to build and develop inside of that line, but not outside. This is why it's possible to drive 30 or 40 minutes west of Portland and be in rural areas with farms, but little development.

Critics say the UGB is also part of the reason that homes cost so much inside Oregon's cities, because it restricts how much land is available.

Then there are the farms. The two areas where consultants found possible sites for semiconductor plants are both located in prime farming areas outside of the urban growth boundary.

Around Hillsboro and North Plains, farmers grow blackberries, raspberries and other crops in the fertile soil. They argue that the dry summer months make it a uniquely perfect area for these crops, and they don't want to see the land converted into industrial sites.

They also argue that an agreement struck just 9 years ago between several groups that were suing each other over land use in this area was supposed to lock in certain rules for 50 years.

Now, people like berry farmer Larry Duyck worry that they'll be betrayed by lawmakers, their agreement upended.

"It was a deal. It was a deal that the farmers, the counties, Metro, the legislature — both the House, the Senate and the Governor signed," said Duyck. "It was something that everybody made an agreement on. It was a deal, it wasn't a bargain. But anyway this took place in 2014. And that was supposed to be a 40- to 50-year process. It was supposed to be good for 40 to 50 years. So right now we're in 9 years. So that's why we strongly oppose any development onto land designated as rural."

The 'regulatory morass'

In addition to that battle, there's another problem — one that might be simple to fix, but the fact that it's still there shows that maybe things aren't so simple. Whenever anything big is built, there are all sorts of regulations meant to ensure that it's done correctly — things like permits.

But deep inside of the government mechanisms that control the permitting processes, there are rumbles of dysfunction. That's according to former state lawmaker, recent gubernatorial candidate and now-KGW political analyst Betsy Johnson.

"Its not just the siting of the chip plant. That's easy to say. That's a land issue and I think it can be rectified fairly easily," Johnson said. "What it doesn't say is the difficulty of securing the permits. The regulatory morass that Oregon puts any company — chip company, any company — through in order to get the permits to build is just unbelievable ... system development charges, permits from this, that and the other agency."

Of course, those permits do exist for a reason — protecting Oregon's environment, for example. But one of Johnson's points is that the process, no matter how necessary, simply isn't efficient.

"We permit sequentially instead of permitting all at once. It's a nightmare and Oregon has a reputation now, through the failure of some very high-profile projects, we have a national if not international reputation as a hard place to do business with," she continued. "So I don't know if it's good enough to say we're gonna throw money at this problem — we've got to break down some of the regulatory barriers."