PORTLAND, Ore. — For working Oregonians, an additional $1,600 each year in income — no strings attached, ostensibly — is nothing to sneeze at. But a proposed measure that would hand that out as a tax credit or send it out as a check is drawing major backlash from both sides of the aisle.

Oregon voters will see Measure 118 on their November ballots. If passed, it would institute a 3% tax on a corporation's total sales in Oregon — everything above $25 million. That money would then be distributed equally among state residents, all ages and income levels, for an estimated $1,600 per person each year.

If voters approve the measure, it would go into effect next year and be paid out in 2026.

The burden would fall on relatively few companies: an estimated 1,422 C-corporations and 791 S-corporations, according to state analysts. That's 2,213 out of a total 120,476 such corporations in the state.

But Measure 118 has garnered a nigh-unprecedented amount of opposition from businesses large and small, elected officials both Democrat and Republican (including Democratic Gov. Tina Kotek), trade groups and local chambers of commerce. All of them agree that the measure is a bad idea, or at least one that isn't well-implemented.

"It may look good on paper, but its flawed approach would punch a huge hole in the state budget and put essential services for low-wage and working families at risk," Kotek told Willamette Week.

On the other hand, the petitioner who brought the measure to the ballot said he wants to see big corporations pay more in taxes, and for everyday people to benefit.

"Number one, giant corporations are not paying their fair share in taxes ... just about everybody agrees with this," said Antonio Gisbert. "And number two, we also noticed that we as working class folks were finding it ever harder to make ends meet.

"And we talk about that now being a problem after all this great inflation that we've just gone through and the pandemic, but really, we started working on this in 2018-2019, before the pandemic, and back then, we were still having trouble making ends meet. And so, we thought, 'What if we put these two concerns together (and) have giant corporations start to pay their fair share in taxes, and then use that money to give people a rebate so they can use their money as they choose.'"

Gisbert thinks more money in the pockets of Oregonians is a good thing for everyone, even businesses.

"Not only is our life going to be materially improved, 1,600 bucks is not going to solve every problem that you have, but it's certainly going to help us," he added. "But also, importantly, it's going to help our community, and this is really important. So when we all go out and we spend our 1,600 bucks — however we think we have to spend that money; it's up to us — then, our economy is going to do better, particularly our Main Street. Our local economies are going to flourish."

The "Oregon Rebate," as it's called, is not without support. It's earned endorsements from the Oregon Progressive Party, the Pacific Green Party and Progressive Democrats of America.

But the coalition that's formed against Measure 118 claims it would be bad for businesses, consumers and the state's General Fund. Hundreds of organizations have signed in opposition against the measure, donating millions to try and defeat it.

The Oregon Working Families Party — a minor political party which sometimes fields its own candidates and sometimes backs candidates from other parties, usually Democrats — said it was initially "looking forward to supporting a measure that funds the care, support and services our families need by making big corporations pay what they owe ... But this measure has flaws, and it would potentially take resources from our communities and harm our families economic well-being."

"We know that wealthy corporations and the politicians that support them have rigged the rules to take from working people. We also know that the only way to unrig them is with measures that allow our communities — especially working families and people left struggling to make ends meet — to get what they need to deliver the quality schools, affordable healthcare and good-paying jobs that ensure we all have a chance at success," continued Annie Naranjo-Rivera, state director of Oregon Working Families Party, in an emailed statement.

The website for supporters of the Oregon Rebate, yesonmeasure118.com, was down at time of publishing, so its unclear what groups continue to endorse it.

Opponents are also calling Measure 118 the biggest tax increase in Oregon history, and they say everyone will be paying more for consumer goods if it passes.

"A tax on sales at every step of the supply chain, it's even worse from a consumer-impact standpoint than a traditional sales tax, which happens once at that final point of sale," said Angela Wilhelms with Oregon Business & Industry, a lobbying group. "Think about an Oregon-made product. You could have a company, let's say a landowner that harvests a tree, and they could have to pay this tax when they sell that lumber or that timber to the mill. The mill might have to pay the tax when they sell a two-by-four to a wholesaler, who would have to pay the tax when they sell it to a retailer, who would have to pay the tax when they sell it to the consumer who just wants to, I don't know, fix a patio or something.

"So this is way worse than a traditional sales tax. It's almost like a hidden tax ... but I think at the end of the day, consumers know that they're going to end up paying for this, and they're going to end up paying for it, sometimes one, two, three or even four times over before the day is done."

Gisbert said he disagrees with that prediction, and that large corporations are paying hardly anything in taxes compared with local small businesses. He believes Measure 118 would balance that disparity out.

"The owner of your local coffee shop is paying taxes for that coffee shop in the range of between 4.75% and 9%," Gisbert said. "On the other hand, a giant coffee chain would be paying less than 0.12%. So that's just unfair, right? And one of the things that that Measure 118 does — and it's not just me saying this, also the LRO says this — is that it balances the playing field."

By the numbers

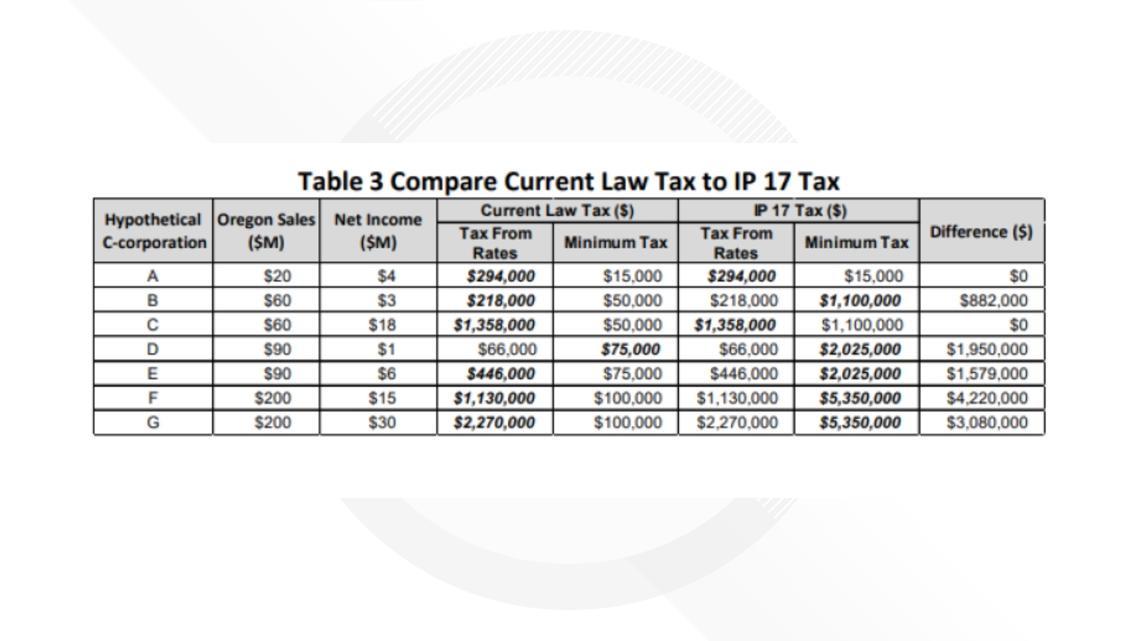

The LRO is the Oregon Legislative Revenue Office, and they did indeed conduct an analysis of Measure 118. It appears true, according to the office's analysis, that corporations with sales of $25 million or below can end up with a higher effective tax rate than corporations with dramatically higher sales — but that also hinges on how much profit the corporations make, which is where most of Oregon's corporate taxes come in.

Anther LRO finding was that Measure 118 would have "significant implications for the state's General Fund" because most corporations currently pay a tax on their profits, which feeds into the state's coffers. Instead, they'd pay the tax on sales, altering the structure of how the state takes in revenue.

The LRO determined that Measure 118 would result in a negative cash flow because the increase in those tax collections could be less than the amount required to fund the rebate program and the rebates themselves. Oregon would also see a reduction in the state's rainy-day fund and an expected 1.3% increase in inflation.

Finally, the LRO found that the Oregon Rebate would conflict with the state's corporate "kicker," which goes toward schools in the state, because the two would be (perhaps unintentionally) competing for the same funds under the measure's current language. There are some similarly odd interactions with fuel tax contributions to the state Highway Fund.

The group Tax Fairness for Oregon, which typically advocates for higher taxes on corporations, called the measure "a hot mess." They described it as poorly written and ignorant of the impacts on Oregon's General Fund, not to mention that people receiving federal benefits could lose them if the rebate can be considered income.

The Oregon Center for Public Policy, which advocates for cash payments to families, agreed with that assessment.

Gisbert said his campaign has a plan to work with the legislature on implementation, and he doesn't think it will impact the state or people receiving federal benefits.

But many lawmakers stridently disagree — and on both sides of the aisle. Oregon's top Democrats released a joint statement last month, writing, "In these tough times, we all want working families to get every break they can, but Measure 118 is not the answer. We have grave concerns it will slow job growth and cause cuts to critical services. As a matter of public policy, we believe this is a bad deal for Oregonians."

The Senate Republican caucus said, "It threatens our economic stability by driving up costs for businesses and consumers, leading to widespread job losses and higher prices for goods and services. This measure will result in severe cuts to essential public services, including education, public safety, and infrastructure. We cannot afford to gamble with Oregon's future on unproven and risky policies."

Measure 118 has also received criticism for its financial backers, with the Oregon Capital Chronicle reporting that a fair number of them are wealthy Californians. After the backlash to Measure 110 and its partial rollback — another measure largely backed by out-of-state interests and criticized for its flawed implementation — there's more distrust this election for Oregon becoming the foremost laboratory of democracy in the U.S.