PORTLAND, Ore. — Since the COVID-19 pandemic swept into Oregon, nearly a million people have become sick with the virus. For most people, that sickness was merely unpleasant for a time — and then it passed relatively quickly. But for others, catching the virus was only the beginning.

“Long COVID-19,” symptoms that stick around 3 months or more after infection, still torments tens of thousands of people in Oregon. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 15 million Americans currently have some form of long COVID. About 244,000 of those people live in Oregon.

Tom Morse is one of those people. He lives in Lake Oswego with his wife, Chris. Before he caught COVID in February 2022, he never had “unsteady days” like he does now.

In his younger years, Morse rode his bike across America. As he aged, only the type of bike changed (he went recumbent). And still he cruised the Tualatin River with Chris, hiked Mount Hood and kept dreaming up new adventures all the time.

Now, his balance is constantly thrown off, and he struggles with bright lights. It’s been that way since he got his mild case of COVID, which then gave way to debilitating long-term symptoms.

“Because we fought like heck to get a really good neurologist with Kaiser, and they've helped with my vision,” Morse said. “My eye input is now balanced with these. I call them my magic glasses. I never wore glasses. These are not leaving my face because they make it easier to see — somehow the right and left are balanced. The brain doesn't have to work as hard. It seems like all of this stuff somehow makes the brain work harder, or something's going on neurologically.”

Diary of a COVID case

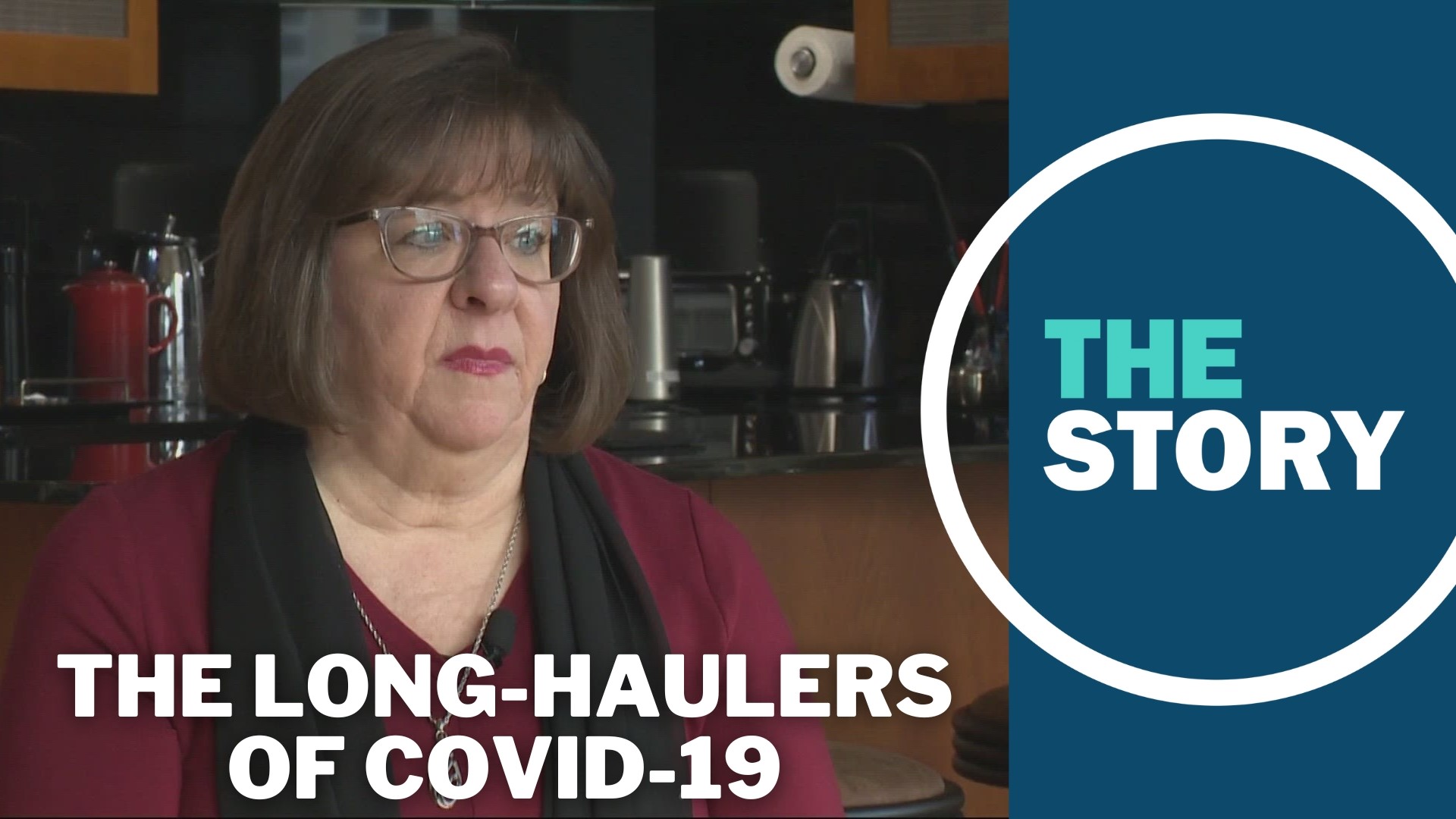

Carolyn Manning can relate to Morse's story. She lives in Portland and got her COVID case early, well before vaccinations were available. This was March 26, 2020.

“I wasn't hospitalized. I had what seemed like a really bad flu and nobody I knew had got it,” she recalled. “So, and the news wasn't talking about it, about the light cases. They just said, you'll either get a light case and it'll be like the flu or you're gonna die.”

Manning, who uses the name Carolyn Ball on Facebook, took to social media to document her COVID journey. On March 26 she announced to the world that she had tested positive for COVID.

“I started posting on Facebook for my friends, an update every day so that they would also know what this experience was — because we weren't getting that information any place else," she said.

Four days later she saw a hopeful sign. Her fever of 103 degrees had broken and she posed for the camera — writing that she couldn’t talk because it made her cough, but she was coming out of the “COVID hole.” Behind the scenes, she was living with the constant coughing, headaches, diarrhea and extreme fatigue.

“And tired, so tired. All I wanted to do was sleep,” she recalled. “And one of the biggest problems when you're sleeping all the time is that you're not drinking anything. So there's the dehydration. So I had to learn to drink Gatorade, which is not my favorite … and then the loss of smell and the loss of taste. That was profound!”

By mid-April, Manning still felt crummy. Still, she posted a picture of some of her favorite snacks — even though she couldn’t taste a thing.

At the 1-year mark, she’d had some ups, but plenty of downs. On Facebook, she admitted to her friends, “Now here it is, one year later, I’m still not over it.”

Pictures from Manning’s earlier life capture the moments that are gone for now. Once the leader of a wine club and a cooking school, working as a client support manager at a tech company, Manning had to step back from her life as a fog enveloped her brain.

“It is the mental equivalent of coming around the corner at 60 miles an hour and hitting a fog bank with your high beams on,” Manning said. “Where all of a sudden I can’t see how to resolve what’s in front of me … so annoying.”

Unable to focus and often exhausted, she eventually went on short-term disability at work — then long-term disability. It’s unclear if she’ll ever be able to return.

“Carolyn is … Carolyn's a great person,” said Dr. Eric Herman.

Dr. Herman leads the long COVID program at Oregon Health & Science University. He is also Manning’s doctor for her ongoing symptoms. Manning gave KGW permission to talk with Herman about her case in order to help people better understand the issue.

"So she was one of those persons that was having significant fatigue. And she was also having those episodic flares of these allergic type symptoms,” Dr. Herman said. “And it can be very confusing to understand all these symptoms if you're not used to seeing it. And so we were able to understand that she had this mast cell activation syndrome and she was experiencing post-exertional malaise.”

Mast cell activation syndrome causes a person to have repeated and severe allergy symptoms that affect several body systems. Post-exertional malaise means that she was exhausted after even the slightest physical activity. Together they’re a nasty combo — and COVID seems to have caused them both.

“We were able to get her on some medicines to try to help these types of symptoms that seemed to have been improving, and she also was able to understand how to control her energy better, how to find that sweet spot of her energy zone so that she didn't go crash,” Dr. Herman continued. “And that she was able to sort of build some stamina, and she too has found that by improving her stamina and her energy conservation, many of her symptoms are starting to improve. And she's seeing some light at the end of the tunnel.”

But Manning is far from cured. And tens of thousands of others like her in the Northwest still struggle with long COVID.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Dr. Herman is part of a national research team of scientists and doctors, all working with patients in order to better understand what is going on.

“There certainly seems to be, once an individual gets infected with the virus, the spike protein can do some pretty dramatic things,” said Dr. Rebecca Kennedy. “It can cause inflammation, changes in the immune system, it can disrupt the way that the body sort of regulates its autonomic nervous system. It can lead to sort of unexpected micro-clots in others. So sometimes there's also a belief that there may be a reservoir of the virus hiding in locations in the body, like shingles. How that can reactivate and maybe … the COVID virus is hiding and it's able to reactivate. So, there's a lot of ongoing investigation to understand that.”

Dr. Kennedy leads the long COVID program at Kaiser Permanente. She too is looking for any hopeful treatments.

“I have a patient who described it as feeling like her body was injected with lead. Just this heaviness and feeling like you can’t do anything. So, this really profound fatigue,” she said.

The problem may reside in the autonomic nervous system, as Dr. Herman mentioned. It controls the automatic parts of the body, things like breathing, heart rate and circulation. The virus that causes COVID-19 may be doing something to throw a wrench into that system.

“More and more the information is supporting this idea that it’s sort of a reset of the autonomic nervous system after someone gets long COVID,” Dr. Kennedy continued. “And so the nervous system sort of gets stuck in hyper-drive mode. So it’s sending down all these signals and that's creating all this change in the function of the body.”

Dr. Kennedy said that the brain could be sending out false signals to the body, creating real impacts to organs and other systems. While she admitted that the research is still in its early stages, she thinks the idea is promising.

“It’s a big problem for those patients and it’s absolutely critical that the medical community address it,” she added.

It’s unclear what the future holds for long COVID patients. Dr. Herman thinks there is hope, both for long COVID patients and for others with conditions that don’t have an obvious cause or cure.

“So I think that it's very hard to show someone I don't have much energy and it's not my fault … or I'm having inflammation-type pain all over my body and we can't find the biomarker that explains it,” Dr. Herman said. “And so by understanding these patients who are clearly suffering and improving with the right support, we're able to show them there's light at the end of the tunnel and we can hopefully improve treatment courses for chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia and maybe other autoimmune disorders that people are suffering from.”

For Carolyn Manning, it’s time to get back to living.

“At this point, I can't promise myself that it’s gonna be different, that I'm gonna go back to what I was. So, I'm moving ahead, I'm no longer on hold,” she said. “It’s why I connected with the OHSU long COVID program and am pursuing some kind of a future — dealing with the hand that I've been dealt."

Tom and Chris Morse are thinking about moving on as well, to whatever their future holds.

“There's definitely a mourning process. We know that the … the future is brighter now than it was a year ago, but we have to accept that it may not be what it was.”