CORVALLIS, Ore. — Think of the fabric of the universe like a blob of really firm of Jell-O. If something hits Jell-O, it's going to jiggle, and if something big enough meets space-time, the so-called fabric of the universe? Same deal.

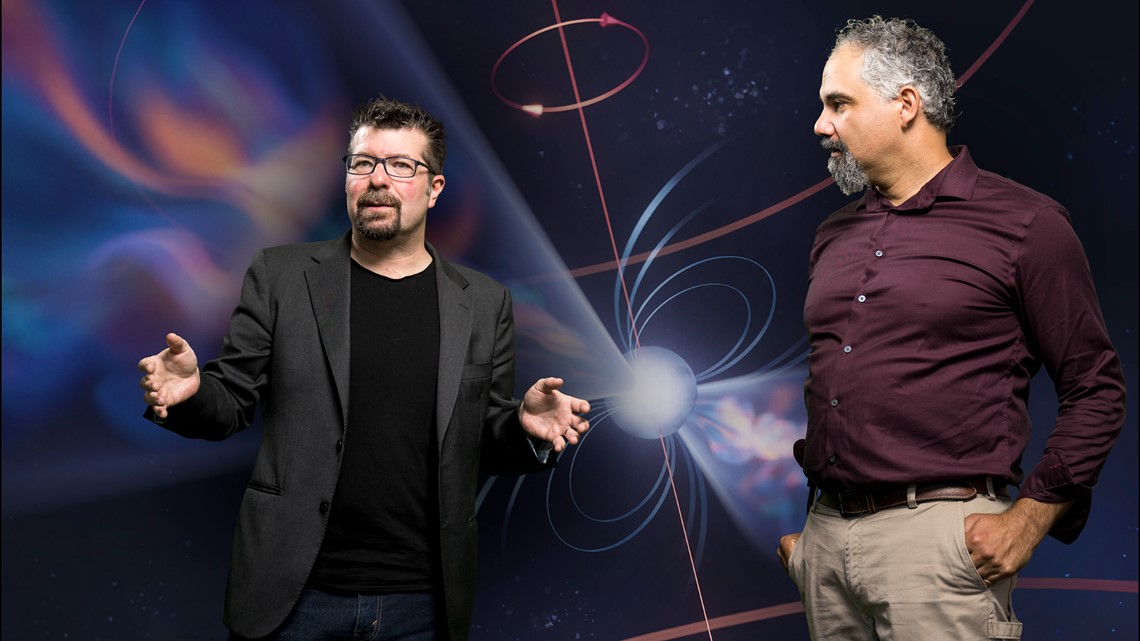

At least, that's how the theory of gravitational waves goes, according to Jeffrey Hazboun, an astrophysicist at Oregon State University.

"Gravitational waves are vibrations in the Jell-O," he said.

Hazboun and his students are part of a huge recent discovery: low-frequency gravitational waves are a ubiquitous feature of the universe.

Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space-time, and Einstein predicted them more than a century ago as part of his theory of relativity.

Hazboun and another OSU professor, Xavier Siemens, are part of an international collaboration of hundreds of scientists called Nanograv, the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves, which hunts for evidence of gravitational waves, especially at low-frequencies.

The hunters search by looking at pulsars, which are what's left behind when massive stars die. They spin through space at regular intervals and emit radio pulses that can be picked up by radio telescopes here on Earth, so scientists peering out into the universe can treat them as giant ticking clocks.

To try to find gravitational waves, the researchers have to keep an eye on the pulses and how often they arrive to see if there are any anomalies.

"If they arrive a little bit earlier or a little bit later, that can be evidence of a gravitational wave passing by, because the length between us is either extended or contracted a little bit," Hazboun said.

It sounds simple, but it was a very long-term project. Gravitational waves were first detected in 2015, but the waves are huge, with a frequency measured in lightyears, so spotting them takes time, especially for low-frequency waves.

"To really see the wave, you need to see from one peak to the next of the waves, and from peak to peak they could be 15 years apart," he said. "So you could see one peak and have to wait 15 years to see the next peak."

And that's exactly what the team did. After analyzing 15 years worth of data from the radio telescopes, the team was able to detect a whole symphony of gravitational waves — some with high frequencies and others with low frequencies — a whole chorus of cosmic waves reverberating through the universe.

So where exactly are all these waves coming from? That's the next big question scientists will be looking to answer, but they do have some ideas.

"The objects that we think we're seeing are supermassive black hole binaries at the centers of galaxies that are billions of times the mass of the sun," Hazboun said.

The gravitational wave discovery is just the beginning of what scientists could someday learn, he said, and it could tell us a lot about what's going on in the universe and where we all came from.

"You can have predictions of things like dark energy or dark matter, big open questions that have ramifications for gravitational waves early in the universe," he said. "So these could be reverberations of the big bang."