PORTLAND, Ore. — The Oregon Department of Transportation has a money problem. The agency is sitting on $4 billion in loans, and its revenues — the amount it takes in from taxes and fees —are not going up as fast as they need to be.

That funding crunch is a big part of the reason ODOT has spent the past six years forging ahead with plans to toll I-5 and I-205 in the Portland metro area. The idea was to supplement flagging fuel tax revenue and bankroll much-needed infrastructure projects.

But tolling, at least for the time being, effectively powered down when Governor Tina Kotek pulled the plug on March 12. She tasked the legislature with considering all possible options for transportation funding during next year's long legislative session.

Not long after that rug pull for the agency, The Story's Pat Dooris sat down with ODOT Director Kris Strickler to talk about the specter of tolling, and where the state may look next for funding. He was appointed to head the agency in the latter half of 2019 by the Oregon Transportation Commission, whose members are selected by the Oregon governor.

Even if the about-face on tolling has left ODOT scrambling, Strickler isn't critical of Kotek's decision.

"Well, honestly, I applaud the governor's leadership," he told Dooris. "As you look to what we've been trying to stand up for years on this program, it's been tough, and you look around and you're trying to serve many things at the same time. You're trying to accommodate the needs of the system by managing congestion, reducing greenhouse gases while also recognizing that there's some finance aspect associated with it, all at a time when really the way to manage that would potentially cause high tolls. And so those kinds of balancing things I think became really difficult — and frankly, you look at what we have to spend over the next year in order to stand up a back office, in order to stand up a marketing effort, in order to stand up roadside inventory, all of those things, I think it was the right time to make the call."

In some ways, Strickler acknowledged, it may have been too much to ask for ODOT to take on both traffic congestion and fundraising at the same time, which tolling was expected to achieve.

"When tolling became part of the equation back in 2017 and the dialogue really started around by pricing, I think there was a lot of effort built into what it could be, right?" Strickler said. "And as we look to what it actually means in application, we had impacts to local jurisdictions and to the public and to the system itself. And those impacts, when trying to balance how to mitigate them along with what you need in order to keep the system running, really became too much to bear for one single program, at least the way it was being set out."

On top of the cost to commuters once tolls began, ODOT was on the verge of spending the money necessary to set up the tolling infrastructure — nearly $100 million. Kotek acted just before the agency could enter into contracts for that work. But there's no question that a backlash from the public factored into the decision.

The future of tolling

Still, tolling may be down, but it's not out. In Kotek's request that the legislature take on ODOT funding, tolling still earned a mention as one potential piece of the solution.

"I didn't see anything taking tolling off the board," Strickler said. "And I think the governor is very well aware of all of the things that we have as far as needs in the system and then potential remedies that might be out there for it. So you don't have to look any further than the Interstate Bridge replacement project ... it still requires tolling and so that will continue. And so that's not off the table at all."

Tolls on the Columbia River bridges have been an entirely separate discussion from ODOT's tolling plans for Portland-area freeways, so those plans have not been impacted by Kotek's intervention. Backers of the new Interstate Bridge have been clear from nearly the get-go that tolling — on both the current bridge and the new — will be necessary to take on a substantial piece of the $6 billion or more price tag.

This has some people concerned that traffic will just divert over to I-205 — but Strickler said there's no plan right now to toll the Glenn Jackson bridge in order to discourage people from making the detour.

"We really relied on the traffic modeling and the modeling effort from the Interstate Bridge replacement team to see what the potential impacts are going to be, and they're still working on those," Strickler said. "I would say at this point it's not what we're looking at. We're not looking at tolling the I-205 bridge. We are really focused on the Interstate Bridge replacement project. There might be impacts and the team will look at how to mitigate those."

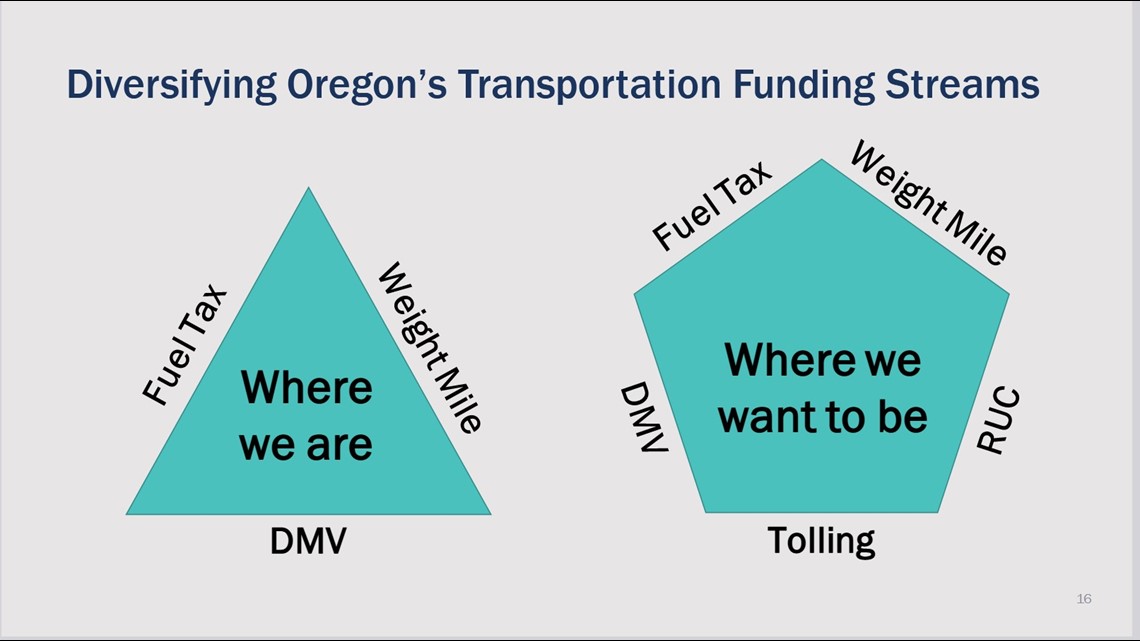

ODOT has not been shy about its future plans. In a June 2023 presentation, the agency identified where it currently gets funding: fuel taxes, weight taxes on trucks, and DMV vehicle registration fees. At the time, they were planning to bolster those revenues in the future with both tolling and something called a "road user charge" — a tax for every mile that someone in Oregon drives.

When the topic of tolling returns — and return it will — just about everything is on the table, assuming there's a way to get the public on board. Dooris asked Strickler if they might try placing tolls just north of Woodburn in order to catch traffic between Portland and Salem.

"Honestly, almost any of these different variations and permutations are a possibility, but they're a possibility that has to come with direction associated with it," Strickler said. "I think the most difficult part is local jurisdictions are struggling to see how it can benefit them overall. I think we've got even state legislators that have been really focused on diving into the details — I think we even called them 'deep dive presentations' when Brendan Finn (manager of ODOT's Urban Mobility Office) and his team went in front of them."

But a lot of the lawmakers with districts that would have been impacted by these early tolling plans were extremely critical of the potential negative impacts, and skeptical of ODOT's assessment of those impacts.

"As you look to just their opinions and the things that they're bringing forward and the concerns that they're raising, you know, there's a constituent base there that is really concerned," Strickler said. "And I think really balancing all of those things isn't really about the permutations of, 'Can you move it a couple hundred yards?' It's really about what is the overall context of the toll system and what's it trying to achieve."

In the future, it seems that ODOT will make a greater effort to let tolling be a grassroots issue — an outgrowth of drivers fed up with congestion instead of an edict handed down from the state.

Filling the financial pothole

There's certainly an urgency for ODOT to bring in more money, because the agency has shouldered a substantial amount of debt. Already, funding levels have limited the agency's ability to keep up with road-related maintenance — and taxpayers may have to backstop the agency when it runs low.

Around the year 2000, ODOT was largely debt-free. But in the years since, the agency has taken on a number of substantial projects that required bonding, causing the agency's debt to balloon in the space of two decades.

"I don't want to quote the exact number, but we have a debt service program that is a significant percentage of our outgoing," Strickler acknowledged. "I would say, just by comparison, we're as indebted as many states across the country. Transportation is struggling nationwide as you start to think about sustainable funding mechanisms going forward. But I can also happily report that we're not as indebted as some of our just most neighboring states."

Specifically, ODOT is paying $553 million every two years on that debt, which means less money to spend on other priorities.

"We know that in the future that we're gonna see declining revenues," Strickler said. "And whether or not that's here today or in the future is in some ways not the point. The point is the inflationary impact, the escalation ... The dollar is not buying what it used to buy, and it's impacting our ability to provide service. So, whether we have debt service associated with the advancing of projects — and I will say I think that's a wise choice and I understand why the legislature did it — it doesn't change the fact we have operational needs and those operational needs really need to be addressed in the near term."

Strickler added that ODOT has not proposed additional borrowing in order to meet those near-term operational needs.

So, how will ODOT find a sustainable source of funding going forward? Strickler indicated that his agency is having good conversations with the legislature regarding the "structural funding of the agency," including about ways that ODOT can diversify its sources of funding. But on the particulars of what will come of it, he punts to lawmakers.

However, he admitted, the road usage charge that showed up in that June 2023 presentation is very much part of the discussion. Essentially, drivers will be paying the state some amount of tax for every mile that they drive.

It's not a new idea — seeing the rise of electric and hybrid vehicles as well as an overall trend of improved fuel-efficiency, Oregon officials started looking into a pay-by-mile system as far back as 2001. A pilot program, OReGO, has quietly been going on for several years now, but it has yet to get any real consideration for widespread implementation.

ODOT sounded the alarm earlier this year about fuel tax revenue tanking. While it's not true that those tax revenues are declining — they went up last year and will likely continue to do so for the time being — they're not increasing as much as they once did. There's no question that fuel taxes have reached a point of diminishing returns, and right now they make up a substantial part of the ODOT budget.

"Coming in the future is, you know, more fuel-efficient vehicles. The future is EV. The future is other funding sources, so you can't stay on gas tax being your source," Strickler said. "But I actually think the most important element of all of this is, whatever fee source is chosen as a potential solution, we have to look at ways to index it. Because if we don't index it — keep pace with inflation, for lack of a better description — then from the day we pass something and the day we move forward, it starts to decline in its buying power right then."

Oregon's fuel taxes have been going up slightly every two years — they increased about 2 cents per gallon in January — but they are not indexed to inflation, which is a big part of the reason that ODOT is in trouble now.

What Strickler doesn't see happening, and he said ODOT has not suggested, is some kind of transportation sales tax. Like changes to Oregon's idiosyncratic kicker law, sales taxes have historically been a third rail in the state.

Tolling, on the other hand, might be just a matter of time — or a matter of timing.

"I think as we look to tolling as a source of funding, it certainly has to be on the table just like it is on the Interstate Bridge replacement project," Strickler said. "That said, I don't think that time is right now, as you're seeing. And so, as we think about what that future looks like, I think it really depends on how you pull together that suite of options — but tolling certainly is an important tool for us, and it's an important tool for, you know, 300 facilities across the country. So it's not new, it is value-based, but it's also difficult."