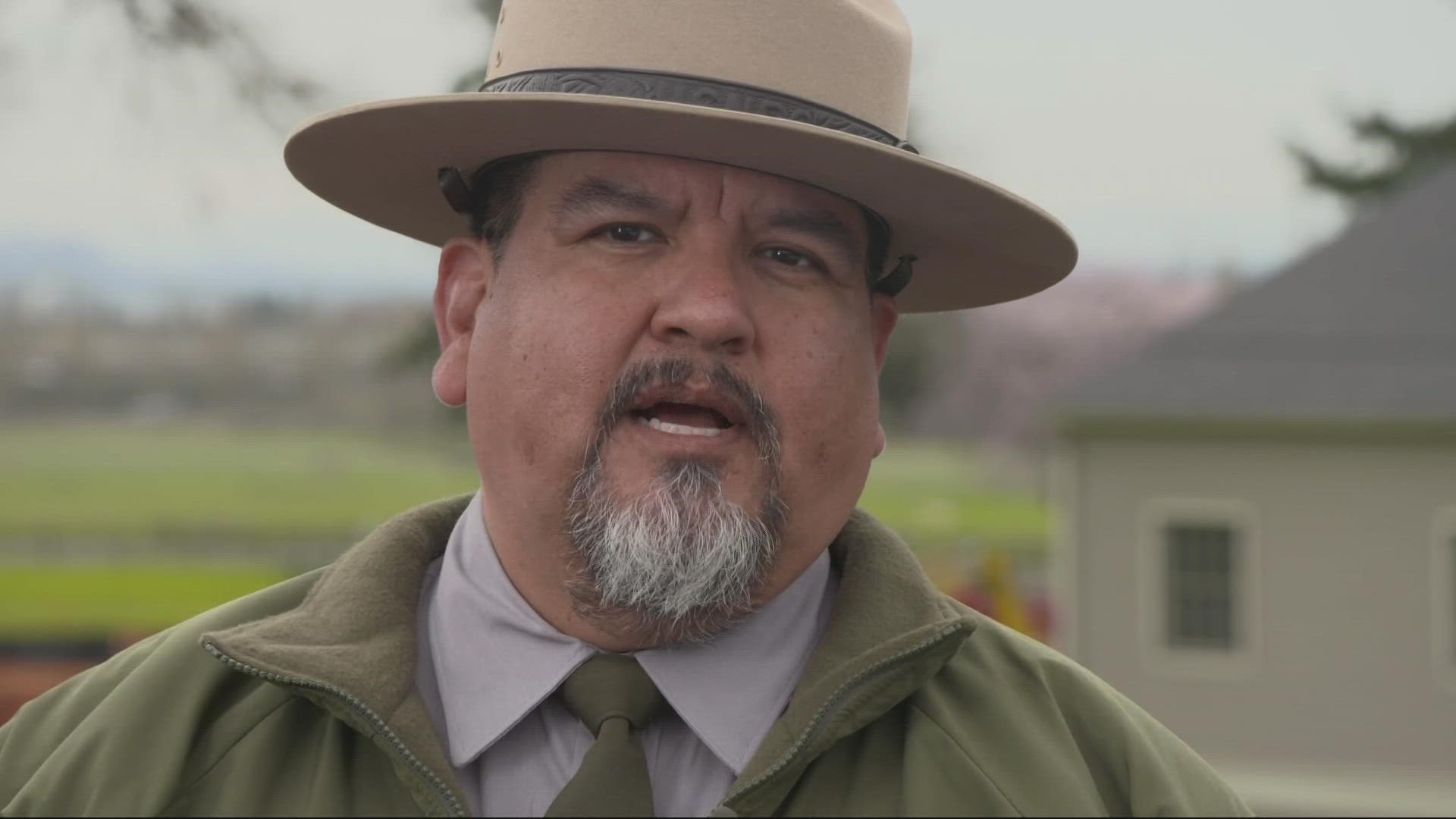

VANCOUVER, Wash. — Chuck Sams began a news conference at Fort Vancouver on Thursday morning with a greeting in his tribal language — something no other director of the National Park Service (NPS) has ever been able to do.

Sams, who was born in Portland and grew up on the Umatilla Reservation, is the first Native American director of the NPS. He visited Fort Vancouver to highlight a renovation project at one of the barracks, Building 993.

The building has stood since 1907 and housed countless soldiers through the years, until it closed in 2012.

"I have to say, as a former service member, it's exciting to know the building will be reused," Sams said. "I lived in barracks myself in the very same setup, and I can imagine the bunks, the rifles stacked in the middle."

A renovation, funded by $15 million from the Great Outdoors Act, will modernize the building and allow the Park Service to rent it out as office space.

The Great Outdoors Act funnels nearly $2 billion a year for five years to the NPS. The money, which comes from lease payments to the government from energy companies drilling on federal lands, will help NPS perform maintenance work that has been put off for years.

Sams also spent time in Oregon on his visit, his first time back to his home state in his new position, but he has deep ties here. Sams was born at Good Samaritan Hospital in Portland, then spent his childhood on the Umatilla Reservation.

Sams is Cayuse and Walla Walla, an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and traces blood ties to the Cocopah in southwest Arizona on his mother's side and Yankton Sioux on his father's side.

"On my non-Indian side, I can go back nine generations to Joseph LaRocque, who came here in 1812, 1813 on the SS Beaver out to Fort Astoria and made his way inland, and worked for the American Fur Trade company and the Hudson Bay Company," Sams added. "Matter of fact, stationed right here at Fort Vancouver."

Asked if he found it difficult, as a Native American, to stand on a military installation that represents the beginning of Europeans taking over Native lands in the Northwest, Sams said no.

"I think that's part of being able to tell the diverse story of America," Sams said. "We have to be able to embrace the good and the controversial and be able to tell that story more fully. If not, then we're not really celebrating the diversity of who we are as Americans."

He said he's visited Fort Vancouver many times — for celebrations, for the reconciliation between the fort and the Nez Perce tribe, and for Memorial Day weekends.

"As a veteran, I don't necessarily see that conflict. Among my own people, under Article 2 of the Treaty of 1855, we allied ourselves with the United States government. The treaty allowed for the president of the United States to arm us with guns and ammunition. That's a recognition that not only has us as a tribal sovereign, but also recognized that we are allied with the United States."

Sams served in the Navy as an aviation intelligence officer and has worked in tribal and state government, as well as with natural resource and conservation nonprofits.

He's been leading the NPS since December of 2021, in charge of an agency with 20,000 employees and 423 parks all over the country.

It's given him an up-close look at our warming climate.

"National parks were ground zero. We've seen a lot of that change happening. Up at Denali we saw as the glaciers started to melt their way back and the tundra started to melt itself off. And we've had land slough off, down in the Everglades we've seen the rise of salt water coming in and affecting the grasslands down there. We have some of the best scientists on the National Park Service staff. If we can combine their work along with the traditional ecological knowledge of the tribes throughout the United States, we can find some resiliency and planning that will help us combat the climate crisis."

Sams said National Parks are also in danger of being over-loved by too many visitors, a problem Oregon is keenly aware of. His team is looking at timed entry slots for visitors and the possibility of using electric vehicles in the parks.

He said he is guided by his upbringing and approach to life.

"I think I bring a unique approach because I believe I am from the landscape. My own creation story tells me that my skin is from the hide of elk, my vision is from the eagle, my hearing is from the owl, that the roots and berries provided my nervous system and that's how I was created as a human being. So that gives a symbiotic relationship," Sams said. "The National Park Service and their mission is all about protecting and preserving and enhancing our natural resources and our cultural resources together, so we can share that not only with this generation but several generations down the road."